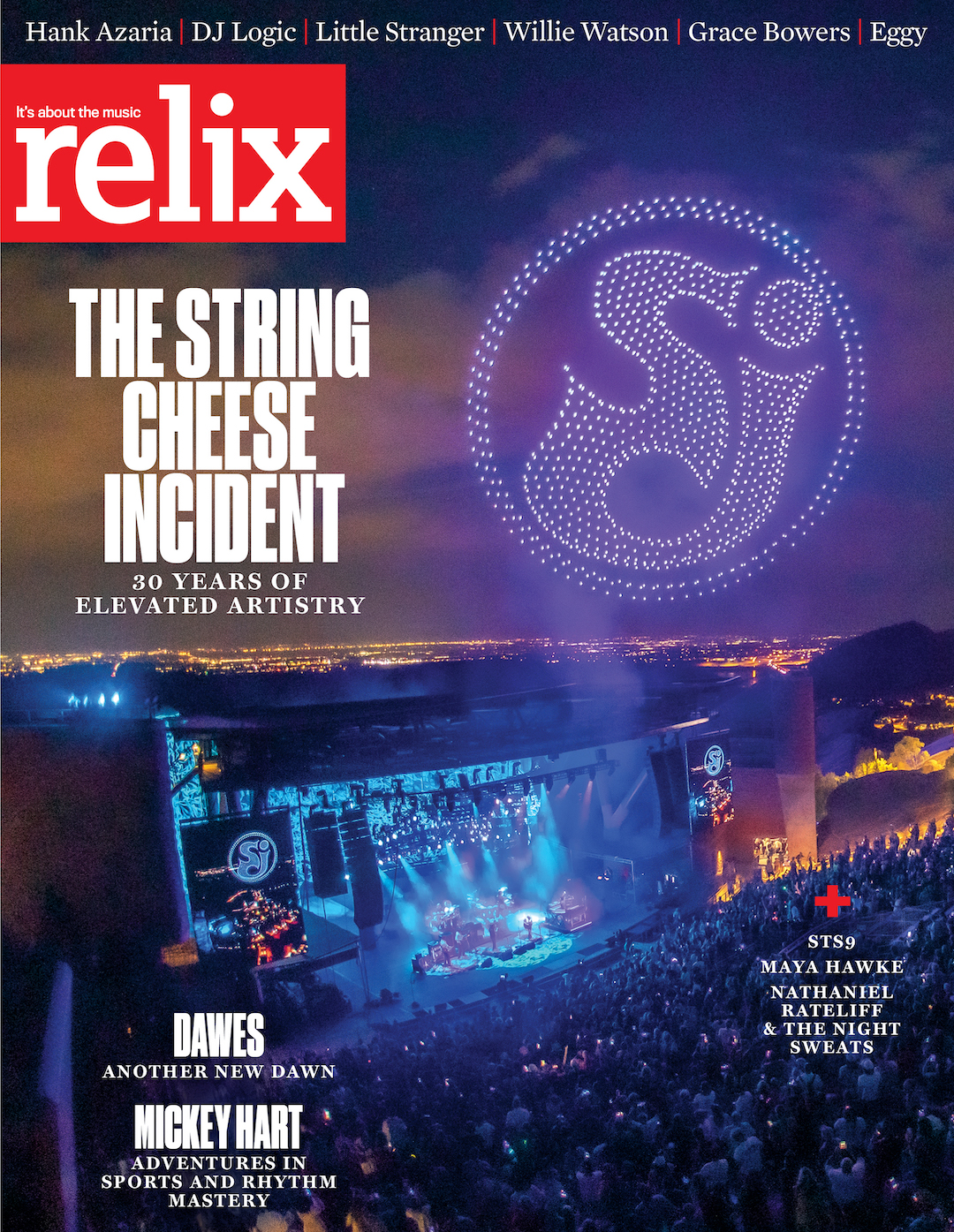

Blues Route: Shemekia Copeland

photo credit: Mike White

Shemekia Copeland was watching the inauguration of the newly installed President of the United States, at home in California on Jan. 20, when her ears suddenly perked up. “We must end this uncivil war that pits red against blue, rural versus urban, conservative versus liberal,” Joe Biden said, unintentionally invoking the name of her late 2020 release on Alligator Records, Uncivil War.

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God! I can’t believe he just said this,’” Copeland says a month into Biden’s term. “Using that title was just awesome.”

If Biden did happen to glean the phrase from her album, then it affirms that he’s got great taste in music. Recorded in Nashville, Uncivil War picks up where Copeland’s 2018 America’s Child left off: The dozen-song set speaks truth to various subjects—both political and nonpolitical. “It’s so uncivil, with the divisiveness and hate going on in the country, even before [the killings of ] George Floyd and Breonna Taylor,” Copeland elaborates. “I’m Black in America, so this is not the first time I’ve seen these things. I do these interviews sometimes and they go, ‘You don’t seem angry.’ Well, I’ve been going through this my whole life.”

The album begins with “Clotilda’s on Fire,” co-written by longtime associate John Hahn and Will Kimbrough, the album’s producer and main guitarist. Backed by the album’s core rhythm section of bassist Lex Price and drummer Pete Abbott, and boasting a nasty lead guitar contribution from Jason Isbell, Copeland dives into a dark chapter that most U.S. history books have largely avoided—the story of the last known slave ship to leave Africa in the 19th century, bound for America.

“Slavery is something that America, since the beginning, has wanted to sweep under the rug and act like it never happened. It’s never been dealt with, never gets talked about,” she says. “And that’s why here, all these hundreds of years later, you have Black Lives Matter. I wanted to bring that story to light.”

Another track, “Apple Pie and A .45,” focuses on gun violence in the States, while “Walk Until I Ride” finds Copeland singing, “So I’m gonna walk until I ride, and I’m gonna keep my head held high/ They can try to take my freedom, they can’t take my pride.”

Not everything is topical in that sense, however. “Dirty Saint,” one of Uncivil War’s highlights, is a tribute to Copeland’s deceased friend and one-time producer, Dr. John, while “Love Song,” the album’s finale, is a cover of a song written by the late Johnny Copeland, Shemekia’s father, a Blues Hall of Fame inductee.

It’s no surprise that it was Johnny who taught Shemekia so much of what she’s put to use during her two[1]plus decades as a professional performer. Whereas Johnny hailed from Texas, the 42-year-old Shemekia born in Harlem and had a very different coming-of-age experience. “Harlem was not like it is now,” she says. “The only white people that came to the neighborhood were coming to my house because my dad was a musician. He had people of all kinds coming to play music, and nobody cared about what color they were.”

That openness has been deep-seated within Shemekia since birth. “My parents never—I mean, never—taught me to hate,” she says. “It wasn’t even heard of in my house.”

She was also taught to keep her mind and ears open to all varieties of music. Uncivil War includes a cover of The Rolling Stones’ “Under My Thumb” that turns the lyrics inside out: In Copeland’s hands it’s the male who’s “a squirmin’ dog who’s just had his day.” And, on America’s Child, Copeland transformed the Kinks’ “I’m Not Like Everybody Else” into an anthem of female empowerment.

“I love that song so much,” Copeland says, “because that is one of my biggest fears, to be like anyone else. [My father] taught me to be original and to be grateful for all the good things that happen because it can all go away in a second.”

Not that it’s likely: With Uncivil War, Copeland’s music has evolved significantly, fulfilling a promise that has been unfolding over the past decade or so. Although she has long been recognized as one of the leading purveyors of contemporary blues music, Copeland—with the help of Hahn, Kimbrough and a team of ace collaborators— has continued to expand her horizons. While Uncivil War includes welcome appearances by guitarists Christone “Kingfish” Ingram and Steve Cropper, both of whom are firmly rooted in blues and R&B worlds, the title track opens up the guest list a bit to include two Americana giants that one would hardly expect to find on a blues album: dobro ace Jerry Douglas and mandolin master Sam Bush.

“I love it,” Copeland says. “I want fiddles and banjos and all that stuff on my records. I want it all because that’s roots music, and that’s what it should be; it should be everything. I love experimenting with it all.”

But the singer also credits the birth of her son, now 4, with showing her that her music can be a tool for positivity and hopefulness. “With all of my earlier records, I didn’t mind bringing up issues and talking about it, and being pissed off and mad about it. But when I had him, I really wanted to help try to change things,” Copeland says.

And should her son one day announce that he too wants to follow in the family footsteps and make music for a living? “I will always encourage him to do what he loves to do,” she says. “But I will tell him he can only get into the music business if he really loves it—if he has a need, if that’s all he thinks about from when he wakes up in the morning until he goes to bed at night. Because that’s what I live for, that’s my main goal: just to get out and make some music.”