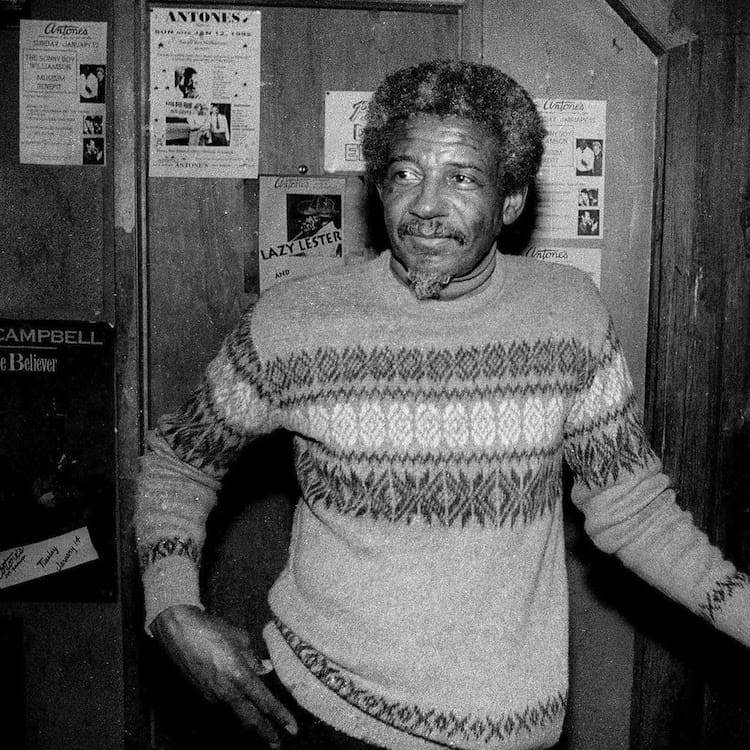

Blues Route: Lazy Lester

By the time Leslie Johnson—a.k.a. bluesman Lazy Lester— passed away in 2018 at the age of 85, he had logged countless miles over the course of his six-plus decades as a road warrior and had created an extensive body of recorded work, most notably for the Nashville-based Excello Records in the 1950s and ‘60s. While Lester may not have left as big a mark as other Louisiana blues greats like Slim Harpo and fellow harmonica virtuoso Little Walter, his admirers were many. The Kinks, whose debut album included a cover of his 1958 waxing “I’m a Lover Not a Fighter”—written by the renowned producer J.D. “Jay” Miller, for whom Lester cut his most cherished sides—were among the significant up-and-comers on both sides of the Atlantic who championed Lester’s work. Other artists, ranging from Dave Edmunds to Dwight Yoakam and Jimmie Vaughan, also count Lazy Lester among their influences.

Besides the sheer quality of his output, Lester also had longevity on his side. Unlike most of his peers who first came to prominence in the 1950s, he was still tearing it up in the late-20th century. One of his regular tour stops was Austin, Texas, where he was often booked by entrepreneur Clifford Antone at the latter’s highly regarded, eponymous blues club. The late Antone also ran a namesake record label, providing an outlet for blues artists who’d been abandoned or ignored altogether by the majors. In 1997, Antone signed Lazy Lester, assigning guitarist Derek O’Brien, a member of the Antone’s house band, to produce the sessions. Together they made two albums, All Over You, released in 1998, and Blues Stop Knockin’, a 2001 title. The former has recently been reissued by Antone’s/ New West, augmented by a bonus track—a live version of the record’s “Nothing but the Devil,” made famous originally by one of Lester’s own blues heroes, Lightnin’ Slim. The song, like many on the set, is a remake of a vintage Jay Miller composition, published under the pseudonym Jay West.

For O’Brien, the experience of collaborating with Lester remains vivid and formative. “I had already listened to him a lot,” he says. “We all thought he was so great. His whole way of singing was completely his own, and those old Excello records were just amazingly wonderful. His voice sounded really well recorded, clear and way out front.”

Without any background on All Over You, a listener could easily presume that it was recorded decades earlier than it was. A refreshing break from so much blues of recent vintage, there’s nothing slick or polished about it: Lazy Lester was the real deal; his music was dusty, dangerous and gritty, downhome and funky. The version of “I’m a Lover Not a Fighter” that appears on the album—as well as tracks like the Jimmy Reed-esque “Strange Things Happen,” the minimalist “My Home Is a Prison,” the shuffling “You’re Gonna Ruin Me Baby” and the rocking “Hello Mary Lee”—exude the sweat and toil so endemic to the electric Southern blues that predates the revival of the genre that kicked in during the mid-‘60s. “We didn’t want to change things,” O’Brien says about his production approach to Lester, “but trying to do that stuff in a modern recording environment was not always easy.”

For the sessions, O’Brien and Antone called on a pair of Austin blues stalwarts, well known to patrons of the latter’s club: bassist Sarah Brown and drummer Mike Buck. Both were well acquainted with the artist’s history and catalog. Lester played the harp, of course, but he also put down swampy guitar parts, augmenting O’Brien’s own. “He played solo on a couple of songs,” O’Brien says. “I thought of him as a harmonica player and singer/songwriter guy, but one thing I learned pretty quickly was that he could play guitar.”

Beyond that, says the producer, “We were almost looking for direction from him, like, ‘Is this OK, Lester? Are we doing all right?’ We weren’t trying to reinvent the wheel or anything. On those old records, you can hear the voice clear as a bell. And Lester is so soulful, he’s got so much character. I wasn’t going to tell him how to think of anything. He was a dream to work with, and I think he knew everybody was trying hard to do their best.”

O’Brien relished the experience not only of working with Lester in the studio, but also of getting to know him on a personal basis. “He was a really funny guy,” he says. “He would tell jokes and he had all these sayings, like, ‘I got no place to go, and nothing to do when I get there.’ They sound like clichés, but then I thought, ‘I’ve never heard anybody else say that.’ He had a great way with words, conversationally. He was also ready for any situation, always kind of happy and he brought joy to everybody around him. Lester was nice to everybody, but he also didn’t kiss anybody’s ass.”

Sometimes, though, he could also dwell in a world of his own making. O’Brien remembers one time when Bruce Willis came to Antone’s to see Lester–the actor was a fan. “Clifford [Antone] said, ‘Lester, this is Bruce Willis. He’d like to meet you.’ They shook hands and Lester said, ‘Nice to meet you. Who do you play with?’ He thought [Willis] was just another musician. He was super unique and sounded like nobody else—this great, mysterious guy who was just himself 100% of the time.”