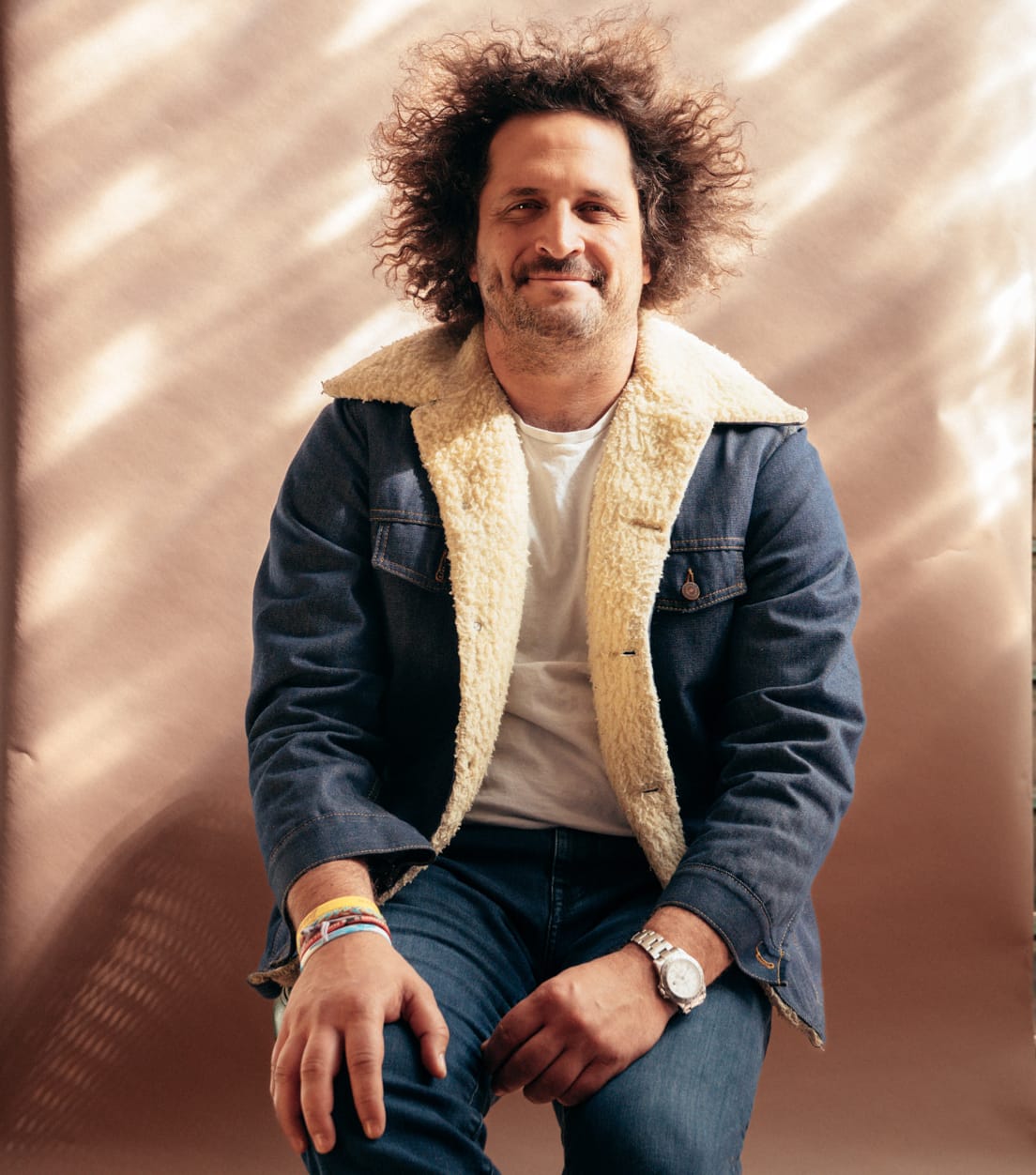

Andy Frasco: Running The Point

Photo credit : Maddy B / @maddybcreates

**

Andy Frasco has the mentality and flair of an all-NBA point guard.

When he performs with his longtime group The U.N., Frasco bounds across the stage and occasionally dives into the audience, where he’s a dynamic scoring threat. However, while his physical play draws attention, he’s a facilitator at heart, bobbing and weaving as he deftly dishes an assist to a bandmate.

This basketball reference is apt as Frasco, a Los Angeles native, often performs in Lakers gear, most recently new acquisition Luka Dončić’s No. 77 jersey.

What’s more, he frames the experience in similar terms.

“I’ve never wanted to take the glory,” Frasco says. “Even though I’m running around up there, I give three-fourths of the show to the other band members. I’m always passing the ball, whether it’s to Shawn so he can rip some guitar solos, to Floyd so he can sing some songs or my drummer Andee so he can have his moments.

“The only reason why the band’s called Andy Frasco is that just in case people quit on me, I didn’t want to have to change the name. I knew that I was never going to quit this thing but, in case people left, I didn’t want to have to feel like I had to start over.”

Ever since Frasco left San Francisco State as a 19-year-old freshman with the goal of becoming a professional musician, he’s experienced self-doubt and embodied determination with varying measures of intensity. However, as he prepares to release his 11th album, Growing Pains, his tenacity and fortitude have predominated. It’s been a long time coming.

“I’ve been pretty insecure over the years,” he reveals. “I think that’s why I got into one-night stands and drugs. But something I’ve been saying a lot lately is that it took me 37 years to find myself.”

Looking back from his present-day perch as a venerable creative entity—who maintains an active tour schedule, regularly composes new material and hosts a spirited weekly podcast, among other endeavors— Frasco acknowledges that his personal growing pains left him off-kilter and out of position for many years.

As a preteen hoopster, he had the body of a center but the mindset of a playmaker. At age 12, Frasco stood six foot one, so his coaches pushed him to develop the skills of a ‘90s big man. They kept him close to the hoop looking for rebounds and easy buckets rather than helping to spread the floor and distribute the ball, as young people are taught today, no matter their position.

The nature of this training became an issue over the ensuing years when Frasco’s height plateaued and he increasingly faced off against towering opponents in the post.

He recalls, “Basketball was my whole life. I was on every tournament team when I was a kid. Tim Duncan, Ben Wallace and Shaq—those were my guys. But then I didn’t get much taller and I had an identity crisis that I wasn’t good enough. That’s when I started getting insecure and kind of took it hard on myself.

“I also started getting chubby and I got picked on hard. When that happened it pushed me to go into full beast mode. I finally developed some confidence because I was working at record labels in high school. My first internships were at Drive through Records and Capitol Records, where I was booking bands. I took that seriously and it also helped me feel like I was fitting in.”

This sentiment eventually prompted Frasco’s fateful decision to withdraw from college. He also points to an inspiring Damien Rice show and the encouragement he received from his Introductory Philosophy professor Jeff Bowling, along with a couple piano lessons from Jeff’s wife Holly Bowling (who Frasco finally reconnected with at Red Rocks last fall).

While it was a bold move to take his bar mitzvah money, purchase a van and travel across the country, picking up gigs and musical collaborators along the way, it felt almost inevitable to Frasco.

“I just believed in the power of music,” he reflects. “I used to Craigslist musicians in every single city I played. I would go to these towns and just Chuck Berry it. That was where The U.N. started. I would be out there with whomever showed up to the gigs.”

Like Berry, he would travel from town to town by himself, without a steady touring group to his name. Frasco also approached the task in a manner akin to a baseball player barnstorming across the U.S. in the 1930s.

“I was like a third-base coach,” he says. “I would write these two-and-three chord songs that the people on Craigslist could learn how to play live onstage without a rehearsal. A third-base coach can’t yell instructions to a runner on first or second base. So I learned hand signs, teaching the bass player or the drummer to go into double time. I didn’t know how to say legato. All I knew was sports, where they’d say, ‘Hit to the post! Move your feet a little left so we can get the runner from first to second!’ I started watching all these coaches so I could give cues without screaming in the microphone, ‘We’re going into a double time!’”

Frasco kept the faith and traveled the country this way for nearly five years, playing pick-up gigs with the locals. Then a more steady team of collaborators began to coalescence.

“I think the first guy I had who was a lifer was [saxophonist] Ernie Chang,” Frasco recalls. “Then there was Shawn [Eckels], although in the beginning, he had one foot in and one foot out because he had his other band Speakeasy. Then I hired Andee Avila, who was also a little bit in and out. Through all that, we probably had 15 bass players, but when I hired Floyd Kellogg, that’s when everyone stopped thinking it was the Andy Frasco project.”

Kellogg had been a member of Spookie Daly Pride, and Frasco recounts, “When we were having our latest bass player trouble, Shawn told me about him. He said that in Spookie’s show, Floyd would be inside a trash can. People would kick the trash can and he’d still be playing bass perfectly until he popped up for the last song. I was like, ‘This guy sounds perfect.’” The complication was that Floyd lived on Nantucket and it’s not cheap to fly out of there.

“But we booked a random show there where he played with us and fit the band so insanely that I was like, ‘Alright, let’s just figure it out,’” Frasco remembers. “I felt like we’d found our missing piece. We had the other pieces, we just didn’t have the bass player who wanted to be our guy. Once we found him, it was off to the races. We had an identity, we had a process, we had a family, we had a tribe. That’s when we started getting successful.”

Unfortunately the road can take its toll on a musician, particularly given the pace that Andy Frasco & The U.N. have maintained while building a fan base the old fashioned way, one town at a time. As a result, Chang recently stepped away from the group. Frasco explains, “It was hard for him, but he just had a kid, which is something he’d wanted to do.”

The current touring roster includes Eckels, Avila and Kellogg along with saxophonist Sam Kelly, guitarist Andrew Cooney and fiddler Allie Kral (Cornmeal, Yonder Mountain String Band). The group’s animated live performances continue to generate accolades and acolytes—they’ve confirmed a steady slate of headlining gigs and prime festival slots into the fall.

Andy Frasco & The U.N.: Allie Kral, Floyd Kellogg, Frasco, Shawn Eckels, Andee Avila, Andrew Cooney and Sam Kelly (l-r) (photo credit: Alec Basse / @bassealec)

Beyond his kinetic, avuncular stage presence, Frasco actively fosters connections with fans outside of the performance setting. He offers pithy, uplifting Monday Motivations via social media. His humor and insight are on display each week via Andy Frasco’s World Saving Podcast, now in its eighth season with over 300 episodes to its credit.

When asked about the commonalities across these ventures, he responds, “I realized early on that my gift was to glue people together and connect them, as a point guard on the basketball court or a catcher on the baseball field. These days, when I’m gluing things together—whether I’m connecting with my bandmates, connecting with my fans or connecting with guests and listeners on the podcast—that’s when I feel most fulfilled.”

Still, Frasco reveals that his work ethic has been prompted by some longstanding struggles with self-worth.

“I hate to make every reference be basketball, but I’ve seen how Luka Dončić, this killer on the court, also has a vulnerability off the court. I saw that when the Lakers made their first trip with Luka to Dallas [where Dončić had played his entire career before a surprise trade in February]. I think that’s why I fell in love with being on stage—I could be this invincible thing, even though when I’m off the stage, I’m still that sensitive kid who got bullied in middle school. I think that’s why I work so hard. I’ve also had this chip on my shoulder that, even if people thought I was a good entertainer, I couldn’t be part of the club because they didn’t think I was a good enough songwriter or musician. I think that insecurity is what’s fueled me.”

It’s also led him to Nashville, where he’s been honing his chops while creating new material.

“I’ve been playing 200 shows a year for the past few years, and we have off on Mondays and Tuesdays. So I’ll fly in and meet with other people. Eventually, I found this community of songwriters who welcomed me into their circle—someone like Chris Gelbuda. He writes songs for Zac Brown and Meghan Trainor, but his favorite band is Phish. He understands my world because he’s lived it.”

Frasco has not focused exclusively on writing for himself. He notes, “Me and Gelbuda just sold a song to Zac Brown and Snoop Dogg. It’s crazy. We gave it to Zac and then he got it to Snoop Dogg. I feel like I’m finally making some headway.”

This burgeoning facility elevates Growing Pains. The lyrical themes span Frasco’s career while the musical forms expand his mode of expression. He’s adept at crafting tunes that are introspective ruminations yet also present universal themes. The U.N. provide a euphonious vernacular to tracks that are by turns rollicking, raucous, sweet and soulful.

Frasco is a self-described “collab guy,” particularly in the festival environment, so he embraces this spirit by inviting Mike Gordon, Billy Strings, Daniel Donato and Steve Poltz to join him on “Life is Easy,” while Eric Krasno and G. Love appear on “Swinging for the Fences.”

One could say that this record is a career culmination, except that career remains fluid. Andy Frasco is a five-tool player who continues to test his creative bounds.

“From the very start, I believed that things were going to work out, that there were people in the Midwest who wanted to get out of their town and join a rock and-roll circus,” he remarks. “Did I think it was going to work out earlier in my career than it did? Fuck, yeah. But if you’re in this circus and you’re making this your life, you don’t choose when it’s your turn.

“For a little while, I started not believing in the mission I believed in when I was 19 years old—that this is a life process. You can’t put a timer on something you’ll be doing as a labor of love for the rest of your life. I think of someone like Manu Ginóbili, who got his recognition a little bit later. It’s not about who gets it first. I was starting to become jealous of bands who became popular while I was still in the van going as hard as I did. Then the minute I took my ego out of it, everything started working out. This is the most I’ve ever been in love with being a musician and being someone who is trying to help people get through their day. This is what I was born to do.”

***

I’ve heard Albert Brooks talk about his friendship with John Lennon, which began when Brooks was a stand-up comedian. There are a number of musicians who maintain close relationships with comics, just as you do. From your perspective, what are the common affinities?

I love musicians, but I respect stand-up comedians the most. They’re up there alone. They’re traveling alone. They’re basically making fun of themselves for an hour. Then they have to go back to their hotel by themselves and absorb being ridiculed. I think they’re the strongest people out there. They’re also kind of sad in their own way, like I can be.

I probably relate to stand-up comedians more than musicians because that was the first thing I wanted to do. I didn’t start playing music until I was 19, but I always wanted to be funny. The friends I had in high school were all trying to make each other laugh. Our jam session was sitting around a Starbucks parking lot trying to one-up each other.

Comedians were also the first people to understand what I’m trying to do with this music—making people laugh and making people cry with a full-spectrum show. They kind of nurtured my career by saying, “You’re not a Berklee College of Music kid or a Juilliard grad. You’re fucking Andy Frasco. You weren’t trained by watching Yo-Yo Ma ripping it up at the Hollywood Bowl, you were trained by watching us.” So they considered me one of them, and they were my little safe haven nest that kept me going. They were also the first ones to give me my shot. Gary Gulman let me score his Judd Apatow film. Todd Glass was the first one who watched every live show of mine that he could and talked to me about it. Once you’re in their heart, they’re the sweetest people.

What are the origins of your Monday Motivations? Had you done that in some form when you were younger?

I started out doing those Monday Motivations for myself. I used to write these self-help blogs. Then when COVID hit, and people were really sad, instead of making the blogs, I started making the videos.

A lot of what distracted me when I was younger was worrying about not being accepted. Then at some point more recently, I stopped thinking that I needed to be in someone else’s club. I feel for kids who are getting bullied, especially in this era of Instagram/social media where people are publicly bullying you in front of more people than ever. So I wanted to show people that they’re not alone in this, that even Mr. Happy can be sad as hell.

After a while, I started feeling some pressure because I’m not professionally trained to be anyone’s guidance counselor. So waking up at 9 a.m. after staying up till 6 a.m. and feeling like I had to be smart and witty started to take its toll on me. But then I realized I don’t need to make new stuff, I just need to talk to people about how I feel at this moment because I believe we all go through the same experiences. I believe we all go through heartbreak, although it might be in different forms. So I encourage everyone to keep going.

Is there a particular theme that runs through your podcast?

I think the main theme in my podcast is for people to get out of their own way so they can have passion again. I feel horrible for people who can’t find passion and are stuck in the same thing.

I also feel sad for people who are just phoning it in. I never want to be that guy. The minute I think about phoning in this gig is the minute I need to find something else. It’s too hard in general to do this thing that I’m fortunate enough to be able to do.

Life is about giving it your all every fucking day and doing things you love. Kobe Bryant is my ultimate teacher. He played his ass off until he was in his late 30s. Then he gave his full commitment to getting an Oscar with Dear Basketball. Then he gave his full effort to being Gianna’s basketball coach.

People also have this backup plan idea. They settle on a job just so they can be comfortable when their bones are breaking. I’ve never understood that philosophy. They’re like, “Oh, when I’m 80, I’ll start traveling.” I’m like, “You won’t be able to walk, bro. Where are you going to go? Are you going to sit in a hotel and look at the ocean?” I don’t get that. I’m like, “I’m going to live now and I’m going to live until I die.”

I heard an interview with Bill Murray recently that made me think of you, in which he described meeting people on the streets. When it comes to going all in and embracing life, a number of your fans have certain expectations about interacting with you offstage, hoping for an almost larger than-life experience. To what extent are you conscious of trying to deliver on that?

It’s about the community and I’m really proud to be part of that community. It’s something I had in mind from the start and I don’t take it for granted. I feel like the band has turned a corner where people thank us for everything we’re doing—not just the music but the Monday Motivations, hanging out after the shows and going to bars with the fans. Someone will message me and say, “Hey, man, my kid’s here and can’t get into the show. Can you come out and say hi?” It’s about those fans and that community.

I’ve heard a few stories about me that people seem to have made up, which is the funniest thing—“Yeah, Frasco stayed in my house and we ripped nitrous until 8 a.m.” [Laughs.] I used to go out looking for adventure. Now, if I have a moment where adventure shows up, I’ll take it, but I’m also better at owning my own self and saying, “I already had four shots. I don’t need three more.”

I’m still going to bars and hanging out with fans after the show, though. They wait for me backstage and I’ll walk to the bars with them. It’s like the Yellow Brick Road or something. I appreciate the connection we’ve developed.

Having said that, there are moments when I can feel burnt out. Sometimes it’s hard for me to come back to Denver after a two-month tour because I feel like I owe it to folks to go hang out, but I still need to decompress. I’m learning how to say no on occasion.

Air Frasco (photo credit: Adam Berta for Playa Luna Presents)

Your live show is physically demanding. Has it been a challenge with the wear and tear on your body over the years?

There was a time when I’d crowd surf after practically every song. Now I’ll have my stage crew do some of that. I’m learning in the same way that LeBron James changed his game. He can’t be slashing at 40 years old. He had to learn a jump shot.

Joe Walsh was one of the first musicians to pat me on the back. We had opened for him and we were standing backstage after the show. His tour manager said to us: “Just wait by the elevator and if he says anything to you, then you can talk to him.” At first he kind of stormed past but then his wife [Marjorie Bach], who also happens to be Ringo Starr’s sister-in-law, told him: “Just talk to the boys, Joe.” So he came back, gave us a hug and said, “I see you crowd surfing and doing the rock-star thing out there. I used to do that, but I’ll leave that up to you now.”

Bill Burr also said something like that because he had been playing Red Rocks the night before, so he randomly ended up at our show. He was like, “That guy ain’t going to be doing that at 80 years old.”

It kind of hit me that he was right. I have to build a show that’s sustainable for the next 20 years. That Frasco show was sustainable and got me on the map for the first 20, but for the second 20, I have to reinvent myself. I can’t be eating mushrooms on stage anymore. I’ve also eased up on the crowd surfing because people punch me in the nuts. I’ll still do the hora stuff because I’m proud to be Jewish, but I’ve had to adjust my game, and as a result, I became a better songwriter.

Something else I decided to do this year, which benefits the band as a whole, is we have a no drugs policy on the bus. I know rock-and-roll is fun but the music is why we all started this thing and we had to face the harsh reality that we were partying too hard. So I had to lead by example and put down some strict rules. I’m not a saint and I’m not telling anyone not to party—we’re still rock-and roll—but we don’t need to do it until 8 a.m.

Since you mentioned Red Rocks, can you talk about the experience of seeing Holly Bowling there last September?

Holly’s husband Jeff was my philosophy teacher at San Francisco State and he’s the reason I quit college. He told me to follow my heart, which is what a philosophy teacher should tell you.

At that point, I was thinking about becoming a third grade teacher. I love kids and there’s still a kid in me. I had my favorite teacher in third grade and that’s when kids are really starting to become themselves. I feel like my third grade teacher told me I could be whatever I wanted to be, which I keep in mind to this day.

So Jeff recommended me to Holly, who gave me my first piano lesson. Then I went to see Damien Rice and I had an epiphany about what I should be doing. I quit college the next day, bought a van with my bar mitzvah money and left.

I hadn’t really seen Holly since then—it had been about 18 years—but we had this nice moment on stage. I told her I still believed in the advice they had given me when I was 19. She has a kid now, and we brought him out to do some solos. It was full circle.

Moments ago you spoke about your development as a songwriter. Does a particular track on Growing Pains represent that to you?

Yes, “Tears in my Cocaine.” I don’t know how people are going to approach that song, to be honest. But that song means so fucking much to me. It’s vulnerable, it’s honest, and I’ve been there multiple times where I’m sad and it’s Monday and I’ve got to do a Monday Motivation to make everyone happy.

That one began with me and Gelbuda just being sad. It was another 24-hour song session after eight weeks straight on tour. We were burnt out. He was writing songs every single day and I was writing songs and trying to entertain people and trying to get all this stuff done while doing all these podcasts. I was burning the candle at both ends and the song came out of all that.

You also wrote “Try Not to Die” with him. Can you talk about that one?

“Try Not to Die” was the first song I wrote for the record. The idea was that we were trying so hard to keep this dream alive that we were worried about accidentally dying. [Laughs.] So it was kind of hitting me at that moment—“Pay all your bills/ Stay off the pills/ Try not to die.”

A whole whirlwind came out of that for the next year. I was trying to find this growth with all the things that I was suppressing because I was on the road. Even though I told him I didn’t have time to think about that stuff, your demons will stay with you. You can distract yourself all you want, but it’s still there hanging out in that suitcase under your heart. So I needed to write about it.

What led you to open the album with “Crazy Things?”

As I listen to new records and watch bands make new records, you want there to be a sense of differentness in the first song. That’s because, normally, there’s one or two songs on every record that kind of go back to the roots. When you have that type of song as the first song, it kind of puts an idea in the listener’s brain that like, “Oh, this sounds like another fucking Frasco record.”

So I wanted to put a more eclectic song there in this style I was going for, which is this Dr. Dog/folk/Americana thing.

When I make a record, I’m also visualizing song one, song two, song three instead of just writing songs. So this was the last song that we wrote on the record because I was like, “We still don’t have our first song.”

Then we had Floyd produce it. He produces all our weirder indie songs, and we approached it as the Mookie Betts of the lineup. It’s up first and you’re hoping to just get on base. Then once you’re on base, hopefully, people will start understanding the theme of Growing Pains.

How does “What We Used to Be Is Not Who We Are” relate to that theme?

I wrote that with Shawn Eckels. We were talking about our past lives of doing drugs and being depressed and not being accountable, but that we still have each other’s backs.

We’ve had a rough run. Me and Shawn have been together for so long that there are back and forths of us fighting and loving each other and fighting and loving each other.

So that’s kind of this love song to us, saying we don’t need to be the people of our past. We used to feel like we were enslaved to that but we’re not. We can change and grow as people.

When I was 19, I had a dark moment contemplating suicide. Thinking about that moment, I realized how many other people probably have a moment where they are embarrassed of their scars, so they wear wristbands.

We all have a past, but we’ve got to remind ourselves that we could have a future if we allow it.

On the album, that song is followed by “Life Is Easy,” which offers a different tone and perspective. I also enjoy your exchange with Steve Poltz at the end.

“Ain’t life grand, Steve” is my homage to Widespread Panic.

We have so many people on that one because I’m a collab guy, which is something you can see from my festival sets. So with this one I wanted to put everyone on a collab— Mike Gordon, Billy Strings, Daniel Donato, Steve Poltz and Chris Gelbuda.

I wrote it with Steve and Chris. I think Trump was about to get into office and everything was kind of going haywire. So we were like, “Here we go again.” But if you don’t listen to the 24 hour news and you don’t doomscroll on Instagram, and instead you go outside and listen to the birds sing, life actually is pretty beautiful.

Finally, when it comes to the title track, did you write a song to serve an album theme that you’d already had in mind? Or did the song itself help to define that overarching idea?

“Growing Pains” was one of the last songs on the record. The three last songs were “Tears in My Cocaine,” “Growing Pains” and “Crazy Things.”

I knew the theme before I wrote it. With me, every record name is a song name. I was toying with some other ideas, but it’s the theme of me getting older and figuring out how to keep going in life.

A lot of my songs are sad, but they have an optimistic approach to them. There are plenty of people who approach sadness with fucking sadness but, as an optimistic, depressed person, I approach sadness with this idea that there’s always another day to get out of it. So with the Growing Pains name, I think it puts a bow on me figuring out another year of my life.