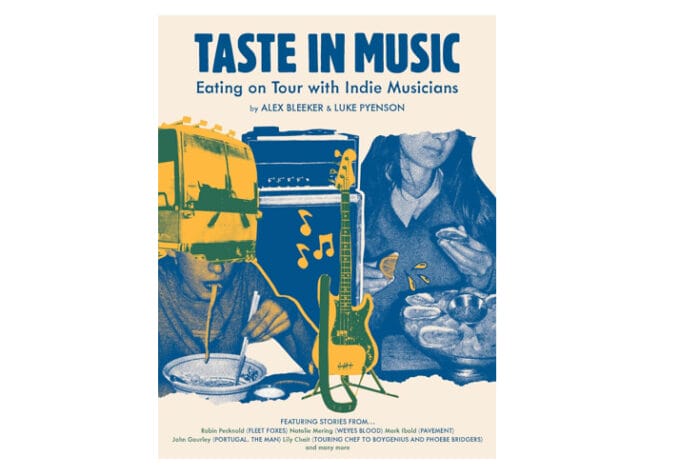

Alex Bleeker Offers a Taste of Tour in His New Book on Music, Travel and Food

Alex Bleeker and Luke Pyenson (photo: Richard Law)

***

“Going on tour has long been a heavily mythologized way of life, with ample touchpoints across pop culture. And yet, those who haven’t gone on tour sometimes lack the context to fully appreciate what it actually means,” Alex Bleeker and Luke Pyenson write in the introduction to their absorbing new book, Taste in Music: Eating on Tour with Indie Musicians. “We’ve gone off to play a single depressing college show in Pennsylvania, only to return home that same night and have someone ask, ‘How was tour?’

“One show in Pennsylvania? That’s not a tour. But tour’s also not Almost Famous, at least not for everyone. In our little corner of the industry, indie-rock, tour is many things—too many things, in fact, to sum up succinctly. And it’s different for all of us. Of course, tour represents the beautiful exchange between band and audience, the singular, ecstatic marvel of live music. But that lasts about an hour, sometimes two, rarely three. The rest of tour—the majority— is governed by two things: travel and food.”

From this starting point, Bleeker and Pyenson offer a variegated account of food consumption on the road, featuring essays by fellow artists such as Kevin Morby (“Thanksgiving in Porto”), Animal Collective’s Brian “Geologist” Weitz (“Eating in the Van”), Fleet Foxes’ Robin Pecknold (“My Savior, My Destroyer, the Subway Veggie Patty”), Bob Mould (“Eating Econo”) and Natalie Mering, aka Weyes Blood (“Tapas Alone”). The pieces are much more than descriptions of favorite meals or restaurants—they’re barely, rarely that—but rather they’re often about companionship and self-care.

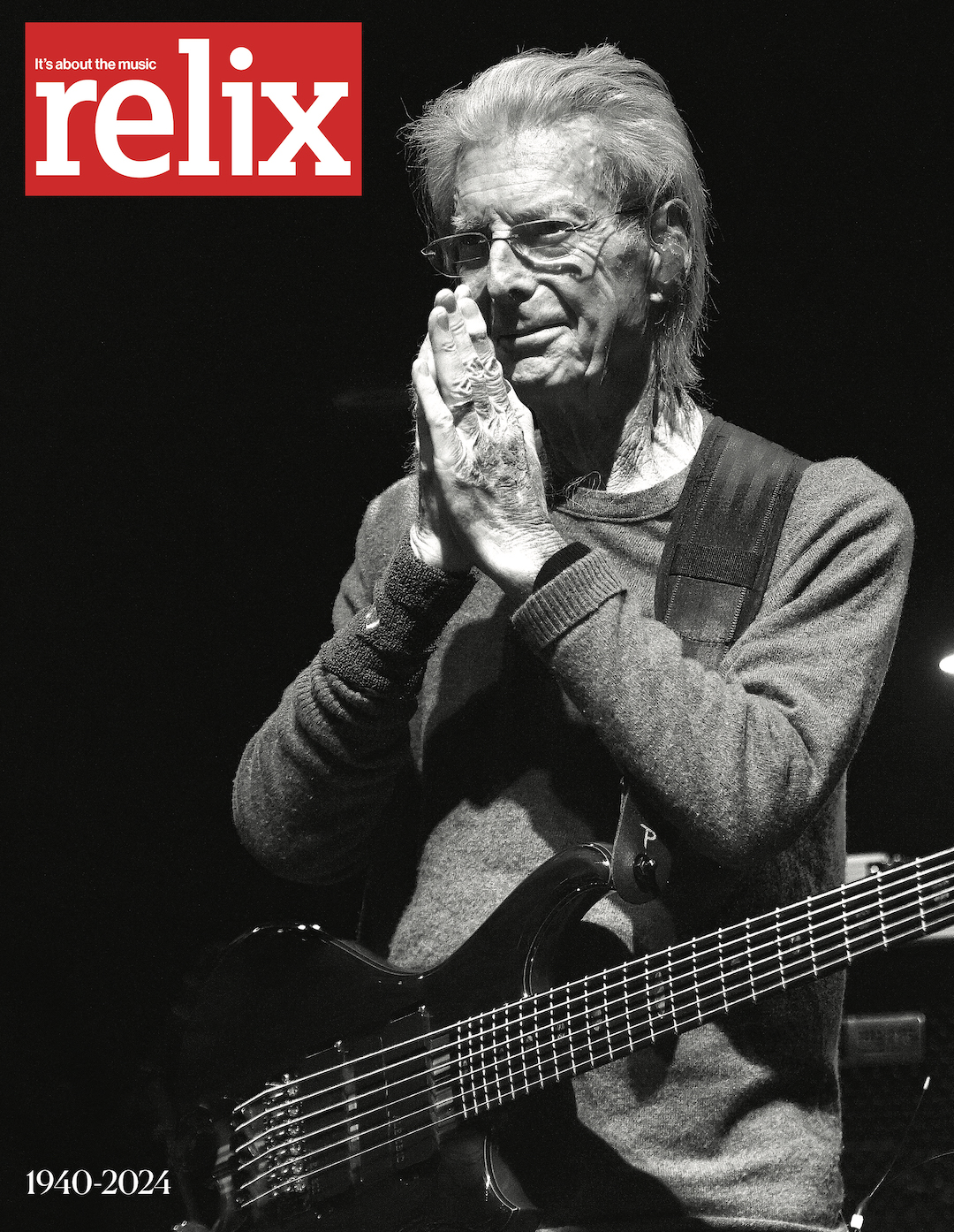

This conversation took place shortly after the passing of Phil Lesh. Bleeker, who plays bass in Real Estate as well as Taper’s Choice—which is described in the book as “a subversive jam band”—offers his thoughts on the iconic musician.

“This might be true for a lot of people in my generation, but ‘Box of Rain’ was, without a doubt, my gateway to the Grateful Dead,” he says. “I was obsessed with The Beatles and I was really into Pink Floyd and I knew about the Grateful Dead, but the Grateful Dead weren’t on classic rock radio when I was 13 in the same way that these other artists were. So I didn’t really have a window to discovery. Then, one day, my mom, who knew Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty from growing up in the ‘70s but was not what we think of as a Deadhead, was like, ‘I need to hear American Beauty, everybody get in the car.’ It was like a bolt of lightning had hit her, so we went down to Barnes & Noble, bought it on CD and then she played it in the car as we were driving back home in suburban New Jersey. When ‘Box of Rain’ came on, I can visualize exactly where I was. It was like this hand of God came down and was like, ‘This is for you, son.’ I was instantly transfixed and that CD became mine the next day. Then I was off to the races, but it was that song in particular that set me off. I feel such an affinity for Phil and his writing, also being a bass player.

“When I heard the news of Phil’s passing, it was emotional. He reached so many people in a really incredible way for so long. Since I live out in Marin, I saw him play at Terrapin Crossroads many times, and his commitment to the music was so strong. I never got to see Jerry, so in a weird way, Phil was my Jerry. He was the member of the band that I always looked up to and felt lucky to see. While I’m sad not to see him play again and I’m sad that he’s gone, I’m also so appreciative of him. So I just want to take a moment to celebrate Phil and say, ‘Thank you.’”

What are the origins of the book and how did it come together?

Even before I started touring, food had been a great motivating factor in everything that I do. I take great pleasure in seeking out interesting or delicious food, as well as downright unique places and things to eat.

When I started touring, that element of travel was on the forefront of my mind. I have this kind of almost obsessive desire to get the best, or most authentic, kind of delicacy in any region. Almost all the traveling I’ve done in my life has been in some way linked to music and touring. Wherever I am, I’m sort of driven to experience a place through its food.

As we know, food says so much about culture, and that has been a great driving force for me as far back as I can remember. So much so that sometimes the meal or the experience of eating will be at least as memorable as any show in any given city. It’s not necessarily even about the food. It’s about who I was with or what the circumstances were.

That’s always been the way I’ve operated as a touring musician. I’ve also found that there are a lot of other touring musicians who operate the same way, including my co-author, Luke Pyenson, who I met on a Real Estate tour. He was the drummer in a band called Frankie Cosmos. We realized that we were both like this, and it was the foundation of our friendship.

For a long time, I had thought of a different sort of book that would be a touring musician’s guide to eating—more of a human-interest kind of coffee table book. Where does Trey get ribs when he plays in St. Louis? Let’s get Bruce talking about disco fries at the diner. That was the first impetus that I had. I see musicians as a roving untapped resource for food and travel writing because musicians go everywhere.

I also assumed kind of wrongly—as you can read in the book—that everyone was exactly like me. So I reached out to Luke. This was during COVID, at a time when I was like, “I’d give anything just to sit in the back of a van for eight hours with my friends.” The way I was feeling was kind of like what Brian from Animal Collective says in his essay.

I was really directionless, so I called Luke and I said, “Hey, should we make that book?” He was into it but he steered us out of the guidebook thing. He said, “First of all, who knows what’s even going to be open when this is over? Also, Yelp exists and Google reviews exist and there are all kinds of people on the internet.” He saw it more as an exploration, with different people telling stories on the road through food.

So we started cold-calling people and saying, “Hey, we’re working on a book. It’s about food on tour. Do you want to talk to us about it?” We had no publisher, no agent, no nothing— but people got it right away and said they were down to talk.

How would you characterize the division of labor with Luke?

Luke inspired me to be able to create a book. He’s been a touring drummer in a band but he’s also a food journalist, so he has more writerly practices and was encouraging. He was like, “I think we should write intros to all of these.” I thought of myself as more of a curatorial sort of person helping put the book together—which I was—but I also wound up doing a fair amount of writing. He really pushed me to get there, which I appreciated.

It was great to be accountable to one another. We each appreciated having another person there who was relying on us to do our part. Early on, a lot of the artists came from our personal relationships and thinking, “I’ve had a great meal with that person.” It sort of spiraled out from there, so it’s our shared community and beyond that’s represented.

Did you have a target audience in mind for the book?

Broadly speaking, we call the people in the book indie. That’s a term that doesn’t really describe anything but it also describes a lot. You’ve got everybody from Chris Franz to DIY stalwarts telling stories. So I certainly thought that fans of these musicians or this scene in general, would want to read it. You have someone like Robin from Fleet Foxes who writes a great essay in the book and, if you like Fleet Foxes, you’d say, “Yeah, I want to know about that guy’s relationship to the Subway veggie patty.”

This is also a different sort of backstage, behind-the-curtain tell-all than Keith Richards’ Life. It’s not sex, drugs, booze and rock-and-roll. It’s really more of a day-in-the-life portrait of what it’s like to be a mid-level touring artist. It’s a way to talk about this level of touring and what it’s like to be on the road. I think you could read this book and find it interesting without necessarily having heard of a single artist.

I think the common perception or representation in popular culture of being on tour is crazy rockstar excess. That’s the imagination of what’s happening, and I’ll say, on the record, that every once in a while that kind of rockstar moment happens. But most of the time, it is a job and I see it as a very good job and a job that I’m lucky to have. I’m not ungrateful, but 95% of our time is not what the audience sees on the stage.

You’ve played a fair amount of gigs outside the United States with Real Estate. Has that touring impacted your view of eating on the road?

This is fresh on my mind because Real Estate just got back from a two-week jaunt in Europe and a lot of the food that you eat on tour is kind of incidental and on the go. You eat what you can grab at a gas station or maybe, if you’re lucky, at a nice grocery store.

In the U.S., there are a couple of regional delicacies at gas stations, like boiled peanuts. But otherwise, it’s pretty much this corporate sameness along the interstate. It’s kind of hard to differentiate and it’s hard to stay healthy out there.

But in Europe, it’s delightful as an American to be in some of these places and be like, “This is the most well-considered, put together, gas-station sandwich I could possibly conceive of. The brie is interacting with this apple and the bread is fresh and this woman standing behind the deli case clearly got here at 6 a.m. to make it.” People over there don’t see this because it’s still gas-station food to them, but it changes the mentality on the tour completely because, when I’m pulling into a gas station and I am in Belgium, I’m excited about what might be in there.

By comparison, I’ll use my great state of New Jersey, which I love, so nobody feels put upon. But in New Jersey, I’m not feeling the exact same way.

That also calls to mind another thing that came up, because we did talk to artists of varying sizes for the book, including artists who have graduated to touring in a bus. A number of them talk wistfully about the earlier days of touring. They’ll say, “Food used to be so important to us, but now we just kind of get catering.” If you’re in the bus, you’ve got to get an Uber to a specific place and you might not necessarily do that. You kind of stick with the touring party. So an interesting, eye-opening thing for me was that, in a lot of ways, the mid-size bands are more nimble, more able to explore culinary delights.

In the book, you’re forthright about acknowledging the body image anxiety you’ve experienced on tour. Can you talk about how that relates to the challenges and pleasures of seeking out those local delicacies you described earlier?

What I’ll say is that it’s really easy to eat non-healthy on tour.

I’ve never struggled with the stereotypical kind of addictions that plague musicians in popular culture. I’m not sober, but I never felt that I drank or used drugs to excess. I think it often happens because of the grueling nature of being on the road. No matter what level you’re at, you’re away from family, there’s repetition— even if it’s the great arenas of the world. Jackson Browne writes about it.

Having said that, I will acknowledge that greasy food is my vice. I am definitely down to go there and I am not abstaining from it entirely when I’m on tour because there are so many amazing offerings of that kind and they’re readily available. But the older I’ve gotten, I’ve come to recognize that it’s not the thing that makes me feel good. It’s not the thing that keeps me healthy. It’s not the thing that fuels the best performance.

In this day and age, we’re often photographed— not just by professional photographers, but by everybody who pulls out their phones and is putting up an Instagram Story. Now that makes sense because it promotes the tour, but there’s this factor that everybody can relate to with a camera in front of them—“Oh, God, is that really what I look like?” That can then feed into saying to yourself, “Maybe I shouldn’t get the cheesesteak in Philly, even though I want it so bad because I’m tired and I’m homesick.”

Balancing all those things is tough. But I end my essay by pointing out that sometimes it really is important to get the cheesesteak because that’s how you know you’re in Philadelphia, although sometimes it’s important to know when not to get it. It’s like the “everything in moderation except moderation” kind of idea. I really think that applies there, but it’s a tough balancing act.

As the pieces came in, was there an essay that surprised you for one reason or another?

A lot of them did, but I’ll say Eric Slick’s special brownies mishap backstage with the preeminent Frank Zappa cover band. Now, when I say that in a sentence, everybody goes, “Oh, yeah, we know what that is.” It’s funny and he talks about accidentally eating too many magic brownies, but there’s so much heart in it. He kind of inspired me. He talked about eating a giant plate of brownies as a kid and how he didn’t know how to take care of himself. He’s exploring it with a heartfelt, emotional, critical eye, taking that subject matter and being funny about it, then kind of bringing it home with the depth that he did. I was just like, “This is the wackiest story in the book, but also one of the sweetest.”

Now that folks have started reading the book, have you received any particularly satisfying feedback?

I think it’s biased, but my dad had heard of zero artists in the book except for maybe the Talking Heads, and he was like, “I’m glued to this thing. It’s a great exploration of this lifestyle.” It was cool for someone like that, who went in without weighing any particular story by the size of the band or artist, to have this complete moment of, “Lemme tell you what my favorite ones are.”

When we were putting it together, we kind of had this festival sort of mentality like, “Let’s make sure everybody’s represented” and “Let’s have another headliner.” But it’s great to leave that mentality and have people be like, “Hey, this is just a great piece of writing by this person.” It’s been really cool to see people react to it in that way.

In thinking back on all the memorable meals you’ve experienced on tour, what’s the first one that comes to mind?

There are so many of them, but this one is fresh in my mind. It just happened. We were in Sweden on a day off and I really appreciate the days off because then you can luxuriate in the meal and not have to think about where you’re going next. So we were in this little town in Sweden on our way to Stockholm when we stopped. We had a hotel on this lake and we had the night off, so we went and got this incredible Scandinavian meal—not a highfalutin Noma kind of thing, just a really good restaurant with incredible fish and high-quality local ingredients.

The food was amazing, but it was more about a nice moment with the band and our tour manager, where we could stop and pause and breathe. We could sit across from each other and appreciate where we were and take a second to be like, “Isn’t it great that we’re all in this small town in Sweden together?” The meal was excellent, but that’s what it was really about.