Aaron Neville Tells It Like It Is

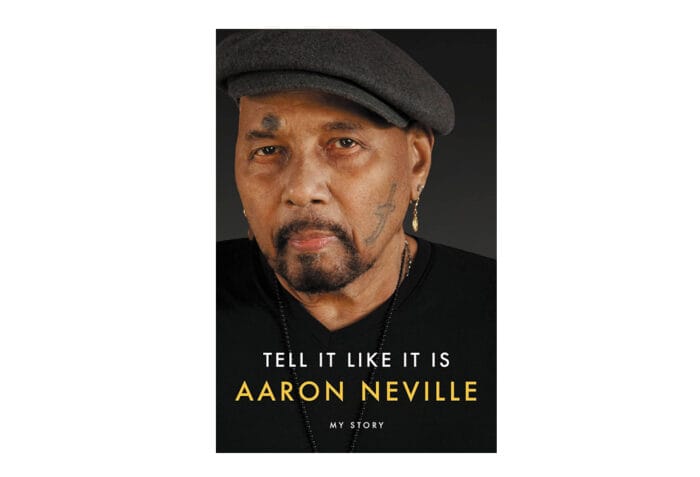

photo: Marc Millman

***

Aaron Neville’s new memoir opens with a stirring epigraph that encapsulates the chronicle to follow. Here he presents the lyrics to the title track of his 1997 album …To Make Me Who I Am.

I’ve walked through this world sometimes without a friend/ My life has been up and down, been close to an end/ But I’ve been through the mill/ And I’ve paid my dues/ Walked so many miles in different peoples shoes/ But I’ve been through the fire/ And I’ve walked in the rain/ I’ve felt the joy and endured the pain/ Once I was a schemer/ But I always was a dreamer/ But it took me who I was and where I’ve been/ To make me who I am.

The song alludes to the chaos and confusion he experienced over the course of a multihued life.

The title to Neville’s autobiography feels almost inevitable, as if willed into existence in 1966 when the singer cut his first hit single, “Tell It Like It Is.” The musician fulfills this promise over the course of the work, offering a candid account of his early years in his native New Orleans, when he struggled with heroin addiction and endured a jail sentence for auto theft, while taking strength from his family and never abandoning his muse. Tell It Like It Is tracks Neville’s early recording experiences, initial successes, subsequent frustrations and eventual triumphs as a member of the mighty Neville Brothers with his siblings Art, Charles and Cyril.

Neville is a man of faith, who retired from touring in 2021, and now lives on a New York farm with his photographer wife. As he pauses to offer his thoughts on Tina Turner—“a very special woman”—he describes opening for her in Europe with the Neville Brothers. “We played in these big soccer arenas with 80,000 people,” he recalls. “It was amazing, and I’d be sure to give thanks. I knew that at one time, I was heading in a different direction.” Still, despite his vivid memories of the road, Tell It Like It Is ends with his simple declaration, “I don’t long for days gone by. I love the days I’m in right now.”

You write that your mom and your uncle could have toured with Louis Prima, but her mom put a stop to that. How did that impact her view of your own budding musical career?

They were the best dance team in New Orleans and had a chance to go on the road with Louis Prima. My grandmother wouldn’t let them go because of the Jim Crow laws. She said they wouldn’t be treated right.

So mama told us that she would never stop any of us from following our dreams. Charles went on the road when he was 15.

As you point out in the book, the Jim Crow laws didn’t just impact your mother’s generation, they were a presence in your life as well.

Yeah, it wasn’t that long ago. Back then, it was the norm. On the bus, they had a piece of wood they called a screen and colored people had to sit behind the screen while white people sat in front of the screen. They had colored and white drinking signs and bathrooms. So you had it mapped out for you—you go here, you don’t go here, you do this, you don’t do that.

As a kid, you lived next door to Red Tyler. Then, after you moved, Clarence Brown was your neighbor. You also went to school with Leo Morris [who later changed his name to Idris Muhammad]. What is it about New Orleans that seems to produce so many musicians?

Well, in New Orleans, you’re born in the music, there’s music all through your life and then you die in music. It’s a lifelong thing and different neighborhoods had different families—the Batiste families, Willie Tee Turbinton and his brother, Deacon John and his family. There are just a bunch of musical families in New Orleans.

Including the Nevilles. In your household, you and your brothers weren’t the only musicians, your sister is in the Dixie Cups.

We were born in it. My brother Art said, when I was a baby in the crib, I’d go, “Ahhhh…” [Singing] until I fell asleep. So I guess I was trying to sing then.

Art started out as the singer in the family, and he had a doo[1]wop group that would sit out on the park bench and harmonize in the evening. They did all the talent shows and they got the girls. Eventually, they let me sing with them. At first, they used to run me away, until they figured I could hold a note. Then they showed me how to do all the harmonies.

In the book, you also mention that while you were in junior high, you were in a doo-wop group that would sing live on the radio. How did that come about?

There were different groups at different schools and disc jockeys would go out to the schools. I was at Samuel J. Green Junior High School and started a doo-wop group with Evelyn Dent, Wallace George, Reynelle Hall and a couple others. I don’t remember the name we went under, but they invited us to sing live on radio. We would do stuff like the Moonglows and the Flamingos.

Much later, you collaborated with Paul Simon, who grew up on that same music and even wrote a song where he name-checks many of the doo-wop groups [“René and Georgette Magritte with Their Dog after the War”].

That music is always in my heart. As a matter of fact, the second to last album I did was My True Story, which was co-produced by Don Was and Keith Richards. Keith talked about the same songs and groups as well. Then he said we were a bunch of old musicians in the studio acting like a bunch of kids. [Laughs.]

Can you remember the first show that you attended as a fan that had a meaningful impact on your future career?

When I was a teenager, I used to hang out at the Dew Drop Inn and Ray Charles came there. Big Joe Turner and Bobby “Blue” Bland did, too.

I can’t remember if I told the story of how I got my first hat. Me and my friend Melvin were out in front of a club called the Blue Eagle when Bobby “Blue” Bland, Junior Parker and B.B. King were playing. We couldn’t go in, so we were outside. In New Orleans, a lot of the guys who worked on the riverfront would buy their clothes on the layaway plan, but they had some expensive clothes. Well, these two guys were off fighting and one of them hit the other and knocked his hat off. I picked up the hat and it was my size, so I ran with it. That’s how I got my first hat. [Laughs.]

You write that the clubs were segregated well into the 1970s and that Mac Rebennack— Dr. John—was arrested multiple times for attending shows at the Dew Drop. You describe him being led off to jail by the cops while saying: “Y’all will have to come back again next week and get me because Ray Charles is going to be here and I’m definitely coming to see him.” Can you talk a little bit about your friendship with him, which began when you were in your teens?

We used hang out in the street together. The first time I ever went into the studio, he was producing somebody and asked me to come sing some background on it, so I did two things with Mac. We’d been playing since we were teenagers.

The first song of your own that you wrote and later recorded was “Every Day.” Had you thought of yourself as a songwriter prior to that point?

No, I hadn’t. How that came about is I was serving time in New Orleans parish prison. You can hear that in the words: “Every day along about noon, I’m dreaming of the day that I’ll be home soon/ Every day along about three/ I’m dreaming that I’ll be free.” Larry McKinley, a disc jockey in New Orleans, got me signed up with Minit Records and I cut the song with Larry Williams. At that session, I played “Every Day” on piano for Allen Toussaint, who was the label’s producer, arranger and songwriter. So I pitched it to Allen, who worked with me on the arrangement. Then he started writing stuff for me in that vein.

After that, the only time I could write is if I was inspired. I couldn’t make myself sit and write something. If I’d see something that caught my attention, I’d write about it. I have a couple of poem books, and right now, I write in my iPhone.

Can you recall the first time you heard yourself on the radio?

Yeah, it was in 1960. When I recorded “Every Day,” I also recorded a B-side that Allen Toussaint wrote called “Over You.” They started playing that song on the radio and it wound up going up the charts.

When I heard myself singing “Every Day,” it was a thrill. I never could stand to hear myself talk. But in the studio, I said, “Wow, what is that?” The singing was cool. [Laughs.]

One point you make is that back in the day, recording engineers were not tweaking vocals. A lot of times, all the musicians would be in the room recording together, which didn’t allow for it. That benefited you because you certainly had the goods.

With “Tell It Like It Is,” I did about four takes on it and they took the first one, which had the innocence. After that, you’re trying to duplicate. With the first, you’re not thinking about it. You’re just doing the song. So the one on the record is the first take.

Speaking of “Tell It Like It Is,” you write that after Frank Sinatra heard the song, he wanted to do something with you, but your manager at that time didn’t inform you of his interest. Did you ever cross paths with Frank?

I never met Frank. I always respected him, though, because I read about him and he was a cool guy. But back in those days, I think God was running interference on me. He said, “You know, Neville, you’re not ready for this right now.” Otherwise, maybe I would have belonged to the 27 Club.

Your group, Sam and the Soul Machine, was a legendary local live band in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, playing multiple sets, five nights a week, sometimes until dawn. You write, “We were all doing a lot of drugs back then, so in the Soul Machine, we took breaks for over an hour and a half looking to score and the audience would just wait for us.” That says quite a bit about your mind-set as well as what you were doing onstage.

Not one person would leave. They all would stay and, when we would come back, they would start applauding. [Laughs.]

I can remember reading a number of stories about the Soul Machine in The Brothers [a collective memoir written by Aaron, Art, Charles and Cyril]. That book came out in 2000 and, over the passing years, I’ve always wondered if some recordings might surface.

No, not really. We were just a band playing different clubs, and that was about the size of it. We never did really record.

In 1976, you and your brothers came together and recorded The Wild Tchoupitoulas album with your Uncle Jolly [George Landy], which set things in motion for the next stage of your career. Can you talk about him?

Jolly was always a big figure in our lives. He was our uncle, my mother’s brother, and he would always visit us. When we were kids, Jolly and my dad worked as Merchant Marines on the ships, going to foreign lands and getting shot at during the war.

He was a figure—a piano player and a singer. Both me and Art were into the piano. At that time, if we went by somebody’s house, we’d play the piano and he would show us different things. We called his style of playing “funky knuckles.” That was a term that came from shooting marbles. [Laughs.]

Later, when he became the big chief for the Wild Tchoupitoulas, he had the music that he wanted to put together and said he wanted his nephews to sing and record with him, along with the group The Meters. Willie Harper also helped with the background vocals.

The four of us had never played together until then. We’d had two or three of us at one time, but never all four. He said, “That’s something your mom would really like— to see ya’ll together.” From there, we formed the Neville Brothers in 1977.

People who only know The Meters’ instrumental songs might not realize that Art also had a great singing voice. In The Brothers, you write, “He could sing like Fats [Domino] until you couldn’t tell them apart, but more than that, he could also sound like himself.”

That’s right. He liked Fat Domino and could do that but he also had far more reach with his voice. He was like a high tenor because of his singing with the doo-woppers and all that. He had this great song that he did called “All These Things” [written by Allen Toussaint and recorded in 1962]. It became a signature song for him but then they began giving him what we called novelty songs and never gave his voice a chance.

He did some great stuff with The Meters. He did a version of “I Want to Make It With You.” I think that was by Bread. He also did a song called “Lover of Love” that was done by Lee Dorsey, and he took it and turned it into his song. He was just a great singer.

After the Neville Brothers formed, one of band’s early supporters was Bill Graham. What was your relationship like with him?

Bill Graham was a great promoter and a great guy. He liked us, so he took the Neville Brothers and he knocked down a lot of barriers. We played with The Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead, Huey Lewis and Carlos Santana. He brought us to Israel. We did the Amnesty Tour with U2, Peter Gabriel, Sting, Miles Davis and Joan Baez, which was a great tour.

One night, we were playing in San Francisco at the Great American Music Hall and Bill said, “I was feeling bad, I was getting ready to leave and y’all started playing. Now, I feel all right. They should make a Neville pill.” [Laughs.]

You mentioned the Grateful Dead, with whom you shared the stage a number of times over the years. How did you get along?

It was a respect thing on both sides. We respected them, they respected us, and we all enjoyed playing with each other. Brian Stoltz, our guitar player, was a bad little dude on guitar. I remember Jerry used to always be watching Brian. [Laughs.] It was wonderful times.

Later on, this young guy came up to me and said, “Mr. Neville, I was at the show when y’all opened up for the Dead. I was the one in the front with the tie-die on.” Oh, you were the one… [Laughs.]

In Tell It Like It Is, you reveal that Jerry had mentioned he’d love to do something with you. Unfortunately, it never came to pass.

Yeah, a couple of times, things like that happened.

Frank Zappa is someone else who wanted to do something, but he passed away and we didn’t get a chance. We had done something with Zappa and he was blown away by my vocals, so he started talking about doing an opera or something like that.

Another musician who pops up throughout the book is James Booker.

James Booker was a friend of the brothers. We went to St. Monica’s Catholic School together, and later on, he went to Xavier Prep High School with my wife Joel. We all were really close.

When he would go overseas, they’d call him the Piano Prince. Then he’d come home and people would say, “Oh, that’s Booker.” He’d be in the Maple Leaf Club with maybe 20 people or something. He wasn’t appreciated.

He would come flying in from Europe, get a taxi and come to me and Joel’s house on Valence St. Then he’d have the taxi sitting out there with the meter running while he’d come in and play our piano. He’d give us a two-hour concert like he was playing at Carnegie Hall. I’d be standing there with my hand on my face looking at him and I’d go, “Damn Booker, you must have four other hands.”

He was just a genius. Look up a song called “The Black Minute Waltz.” It sounds like he’s got five or six hands going on that one. He taught Harry Connick Jr. a lot of stuff too.

If I had any question as to your favorite Neville Brothers record these days, you answer that in the book when you point out that, while on your treadmill, you listen to the Neville Brothers’ Live at Tipitina’s 1982 album. You call it “the funkiest band we ever had” and “some of the greatest music of all time.”

Can’t go wrong with that one. It was a hot night, and I remember we started with Little Willie John’s “Fever” and we funked it up. Then we went through all kinds of great rhythm. So on the treadmill, I walk, I run, I laugh, I smile. It’s real gratifying.

Back then, sometimes we’d have a setlist, but a lot of times, we went off the beaten path because Art liked to hook songs together. We might start one song, then go to another song and then another song. So the song might be 20 minutes long.

I can remember being at Tiptina’s, playing a funky song and seeing one guy who was beating his head up against this iron column to the drum beat. Then I saw some guy bootie-scooting across the floor and found out later they were a district attorney or a lawyer or something like that from Tulane University.

You worked with Eric Krasno on your final studio record [2016’s Apache]. How did you meet him and can you share a bit about that experience?

I had a lot of poetry that I wanted to put to music. One day, I was talking to management— Marc Allan with Red Light Management—and I told him what I wanted to do. He recommended Eric Krasno, they call him Kraz. So he and David Gutter, they got together and helped me put music to a lot of my poems.

They brought out another side of me. People are used to hearing the high notes and all that. While I do a couple of high notes, this is more gritty, more down-to-earth music. It’s sort of like New Orleans mixed with Brooklyn.

In writing this book and looking back on your early days, do you think all the early strife ultimately informed what followed in an essential way or in a parallel universe, could you do without it?

No, it gave me a chance to have compassion for other people going through adversities in life. I knew what I was going through, but I never knew what other guys were going through, so I’d keep them in my prayers.

It’s there in that song I wrote: “It took who I was and where I come from to make me who I am.”