A Life in Focus: The Photography of Graham Nash

photo credit: Amy Grantham

***

“I was 10 years old when my father showed me the magic of photography, and it’s been with me to this day,” Graham Nash says, while tracing his love of the visual medium. This lifelong ardor is well-represented throughout the 200-plus pages of his new fine art book, A Life in Focus: The Photography of Graham Nash, which was released through Insight Editions this fall.

Nash explains in his introduction: “Creativity is a muscle we must exercise; we need to keep the blood rushing through it for it to be able to expand.”

As a result, “Every morning, I grab my camera and say to myself, ‘OK, something fantastic is going to happen to me today.’”

A Life in Focus shares the captivating results as Nash engages the world from his perspective. He captures quiet, contemplative moments with fellow musicians, such as Joni Mitchell, David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Neil Young. He also brings his artist’s eye to the objects and settings that surround him and continue to animate his work.

“Here I am at 80 years old and still taking pictures,” he observes. “I was in my room 10 minutes ago printing images, trying to share my world with people.”

***

In your introduction, you write, “a photographer must have courage to be a good photographer.” Can you describe a situation in which this played a role?

In 1969, I was living with Joni Mitchell, and Joni was doing The Johnny Cash Show in Nashville. It was a very popular television show that was on every single week, like The Ed Sullivan Show. The Crosby, Stills & Nash album had not come out yet and nobody knew who I was but I wanted to take a picture of Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. It takes courage to get up and start pointing a camera at somebody so famous, especially when that person doesn’t know you. That’s the kind of courage you really need when you’re taking what you consider to be interesting photographs.

You mention that, when it comes to your music, you can talk in colors. Do photos ever evoke music for you?

Absolutely. Let’s take an image like Moonrise over Hernandez by Ansel Adams. It’s a very famous photograph. Every photographer knows it. I actually had a copy of that image that was printed before 1945. It was much lighter. Eventually, Ansel Adams took the negative and darkened it so, on every print after 1945, the sky is darker. But, on the print I had, there are great clouds around the moon. The moon wasn’t sticking out so much from a black sky, like in the later prints. When I would look at that photograph and look at the foreground, I could imagine cellos and bass players playing the bass notes of this photograph. Or when I would look up in the sky and see how beautiful the light gray clouds were, I could imagine violas and violins playing a melody. I wasn’t hearing an actual melody, I was experiencing the combination of images and music.

Did the advent of digital photography impact you in any way?

I bought my first digital camera in Tokyo 30 years ago. It was called a da Vinci and the image that came out was almost like the little receipt they print out when you buy something in a store.

But I waited and I waited because I realized that this digital train was coming toward us at a tremendous speed and we either needed get on it or get run over. I waited for digital cameras to approach the resolution of the Tri-X 400 film I was using. Of course, now it’s gone way past that.

So I do use a digital camera right now. I love the fact that I can manipulate these images and get rid of the dust and the scratches while the lights are on. I can clean them up while I’m drinking a cup of tea and watching the news on TV.

It’s like the internet—the great thing that happened was that it gave everybody a voice and the worst thing that happened is that it gave everybody a voice. It’s the same with cameras. Everyone thinks they’re a photographer now. There are about 400 million cameras in America and probably only a few dozen photographers.

Do you think that the proliferation of cameras on all these devices has altered the way that people react when their picture is taken?

I don’t often take pictures of people, but I do realize that they are reacting differently now than they did 30 years ago. Back then, if you took a picture of a crowd of people, nobody cared. But today, people care and sometimes they don’t like their picture being taken so you have to erase that image off your digital camera because they didn’t want to be seen. People are much tighter now than they were back then. They were much looser 30 years ago.

In my world, it also used to be that you had access. Thirty years ago, Jim Marshall was walking onstage and taking pictures right there. Jim, Neal Preston, David Gahr— all the wonderful photographers—took some incredible images. They had courage, there’s no doubt about it.

The access that people have is different nowadays. Most photographers at a concert are given the instructions that they can only shoot the first three songs. They’re told, “My artist gets sweaty after three songs and he doesn’t look good, so you can’t take his picture.”

Things used to be much more happy-golucky. But today, people care a great deal.

As a photographer yourself, when you’re performing, does that impact the way you view the people shooting from the pit?

Yeah, that happens sometimes. I’ll notice someone who I think is a real photographer because he’s only taken four images. Whereas somebody next to him has taken 50 images in hopes of getting one good one. So when I see a real photographer doing his stuff, I’ll open up to him more musically and physically with what I’m doing.

How would you describe the overall relationship between your photography and your music?

It’s all me shooting off my mouth. It’s me writing songs about Trump. It’s me writing songs about falling in love. It’s me writing songs.

It’s also me looking and taking pictures and sharing. I think it comes down to a very simple fact that I see things differently than most people. I think beauty is absolutely everywhere and I like to take pictures of it, although I’m not going to use my camera as my memory. I don’t take pictures of landscapes or mountains or sunsets. I’d rather experience them personally and not take a picture of a sunset with all the other pictures I took that day.

But it’s all just me and my life. I get to share my music and I get to share my images. I couldn’t be happier about it.

***

GIRL WITH UZI SUBMACHINE GUN, 1998

I was rehearsing at The Alley, which is a very famous rehearsal studio in North Hollywood. We had taken a break and right next to it is a hamburger stand where everybody usually goes to get lunch. So I walked over and there’s this little girl in a pretty dress, who was probably three or four years old, sitting alone. It was weird because nobody was with her, like a parent or something. Then, I realized she was sitting next to an Uzi machine gun.

Somebody I spoke to many years ago about that image said, “You’ve gotta understand that’s a real Uzi. That’s not a plastic piece of shit, that’s a real gun.” So there’s the juxtaposition between the innocence of the young girl and the menace of the Uzi machine gun in the same shot.

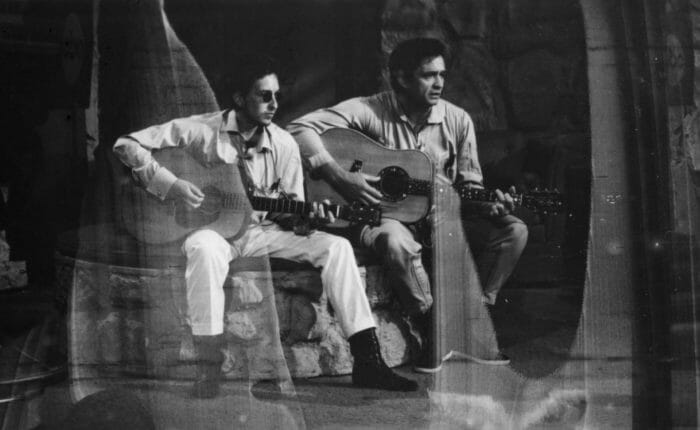

BOB AND JOHNNY II, 1969

This photo of Bob and Johnny was rescued from damaged negatives, which—even in a destroyed state—is still an interesting image. What a great opportunity it was for me to be able to take photographs of two legends of American music. It was obvious that they enjoyed each other’s company.

Again, nobody knew who I was. They knew Bob Dylan, they knew Johnny Cash, and here’s this kid walking up and taking pictures of them. Nobody stopped me, though. They must have just thought that I was this lump of flesh that was attached to Joni Mitchell. But, I was taking pictures that I thought were very cool. Once again, it was courage.

RED CARPET, 2014

Where is that red carpet leading to? The drain. That’s how life is. I didn’t put that there, though. It was just something that happened to me. And God bless it.

CASS ELLIOT, 1969

This is the last image I shot of Cass. I loved her dearly. I thought she was a brilliant woman and, on every album I’ve made since she passed away, I have given her thanks. She knew David and Stephen—she knew that The Byrds had thrown David out. She knew that Buffalo Springfield had broken up. She knew that they were both trying to do an Everly Brothers kind of duo thing and she knew that, if I sang with them, it would be completely different. And that’s exactly what happened.

We were 40 seconds into a song that I rehearsed with them twice, and we had to stop because we started laughing. It was ridiculous. The truth is that The Byrds and The Hollies and Buffalo Springfield were very decent harmony bands, but this sound was very different than anything we had heard before. And we didn’t have to rehearse for a month. The sound of CSN, that sound of me and David and Stephen making our voices into one, happened immediately.

PEACE, 1987

The world is always showing me that there’s beauty everywhere. I was at Hiroshima, a place where over 75,000 people were burnt to death instantly when that bomb went off. I looked on the ground, and there was a cigarette package that said peace.

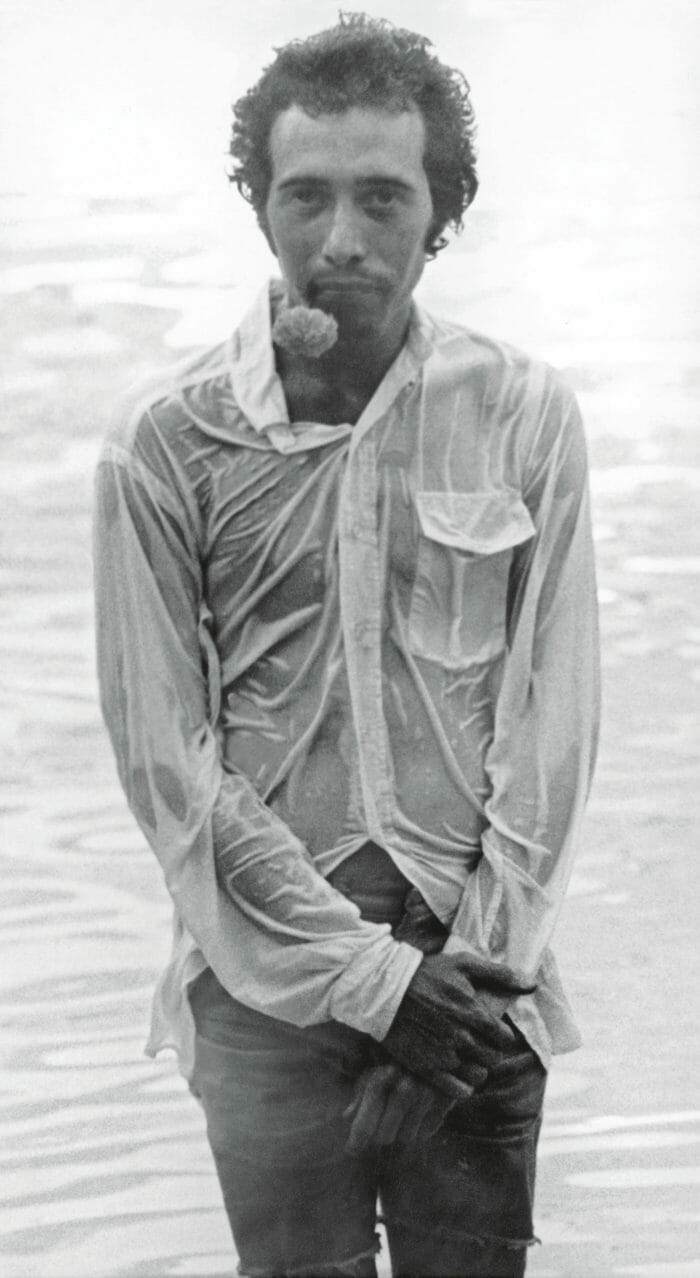

DAVID GEFFEN, 1969

This is at Stephen’s house just after we threw David in the pool. He’s a billionaire right now, so who the fuck can throw David Geffin anywhere anymore? But, back then, he was just our friend. He was moved by our music, and we needed representation in two ways. One, we needed a shark, and that was Geffen. And then two, we needed someone who understood that we were four hippies trying to make our way through a musical world, and that was Elliot Roberts— one of the funniest men I’ve ever known. He could deflate an argument with one line and he was great for us.

One day, we were all at Stephen’s rehearsing and Geffen came by bragging about how much money he was getting for the band. We were thrilled, of course, but after he did all this bragging, we picked him up and threw him in the pool to cool him down.

WINDOW SHOPPING, 1998

I was staying at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel for about a week, so of course I was walking around Beverly Hills trying to find a good image. I came upon the Van Cleef & Arpels jewelry store where I saw this old lady looking in the window. I noticed that, right below her, there was this homeless person sleeping. She wasn’t taking any notice of the person. All she was interested in was the jewelry. She was peering in the window with her face against it, looking at all these jewels—not realizing that there was a jewel lying on the street right below her feet.

THE CONSTITUTION, 2015

I was walking down in the East Village and there was the Constitution written in concrete with all these black shadows all over it. If that’s not a statement on what’s going on today, then I don’t know what is.

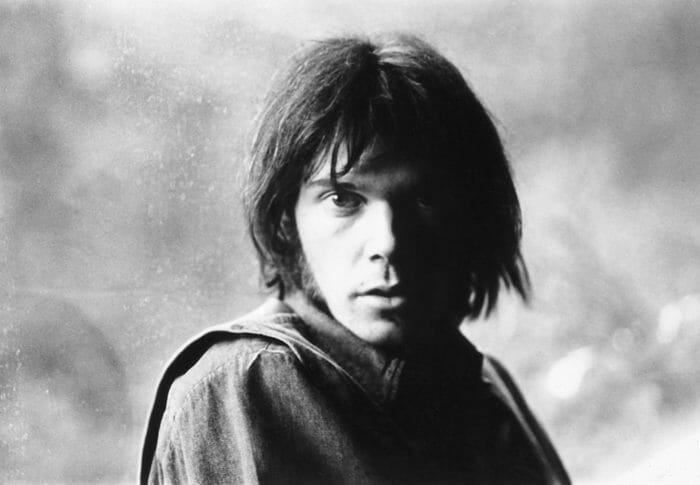

NEIL YOUNG REHEARSING FOR DÉJÀ VU AT STEPHEN’S HOUSE III, 1969

I always carried my camera a lot. David, Stephen and Neil didn’t care what I was doing. They just trusted that I wouldn’t take a picture of them that looked shitty. That’s Neil. That’s the look. He is this unapproachable, untouchable entity and he’s looking at you with those eyes daring you to come up with something that he can’t handle. He’s an amazing man who is totally committed to the music. I love Neil dearly.