Dead & Company: The Music Never Stopped

Dead & Company kick off their Playing in the Sand event tonight, delivering the first of four performances in Cancún, Mexico. To mark the occasion, we’re sharing our April_May 2017 Dead & Company cover story in its entirety for the first time.

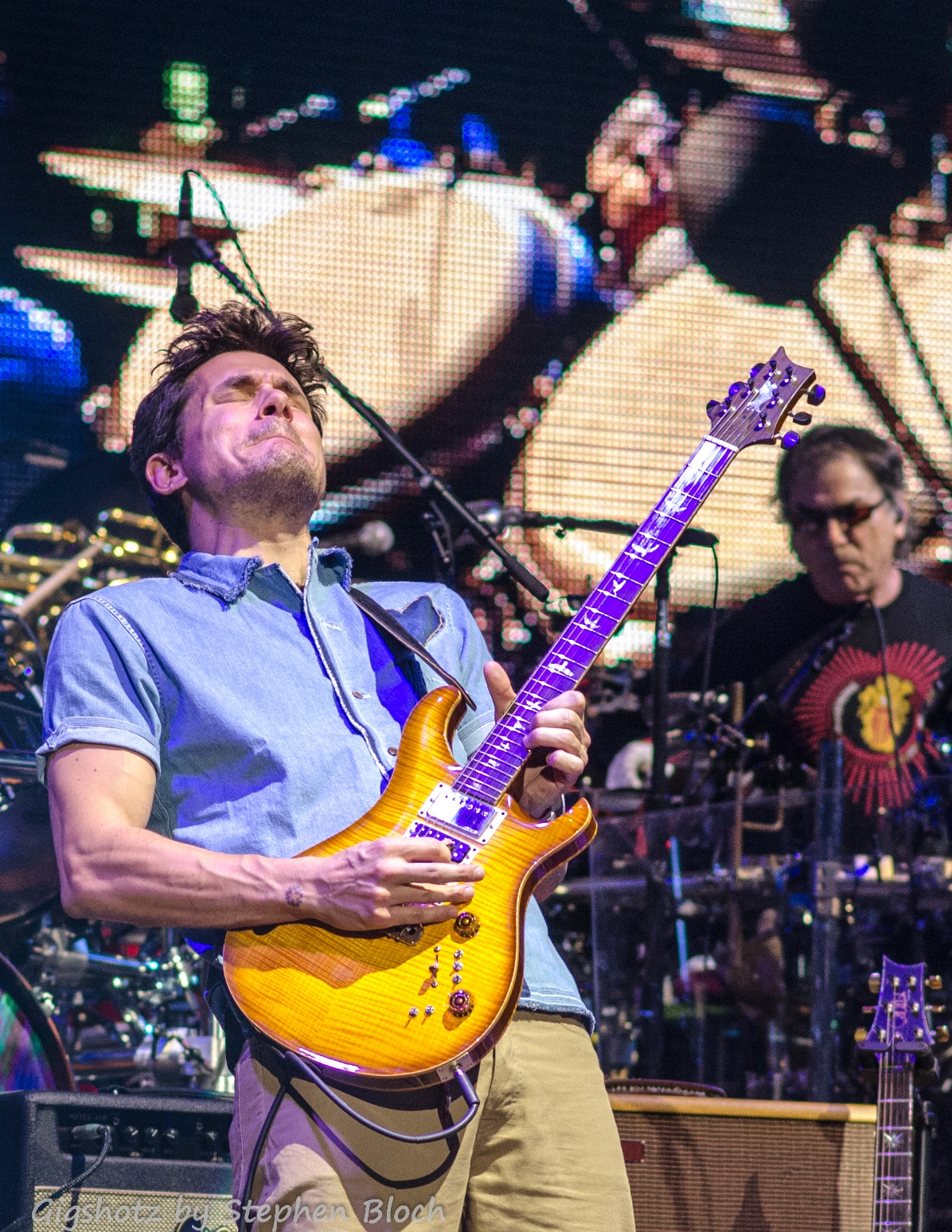

John Mayer hasn’t seen the new Grateful Dead documentary just yet, but he knows exactly when he intends to carve out the requisite four hours needed for a screening of Long Strange Trip.

“After I get off my tour in May, I’m going to reset and watch it as a primer to get into that space again,” he explains. “I would imagine that at the end of watching that movie, even if I wasn’t able to play with those guys, I’d go, ‘Oh God, I would love to be in that band.’ And that really is where it started for me.”

It was back in 2011 when serendipity and a playlist algorithm converged, leading the sweet sounds of “Althea” to reach Mayer’s ears through the Neil Young Pandora channel.

“When you’re listening to music on Pandora, there’s this inherent sense of ‘these are all songs you know but forgot that you wanted to hear.’ Then ‘Althea’ came on, and everything just seemed to stop. I went, ‘What is that?’ because, as a guitar player, I had managed to burrow pretty deep into all the things that can happen on a guitar neck. Guitar players get to a point where they’re deep enough into their instrument where they can visualize what someone’s playing. Especially if I’m falling asleep and listening to music, I can watch the fretboard and map it. But I listened to this, and it was like I had never played an instrument. It inspired this perfect jealousy in me. There’s a certain kind of jealousy an artist can have that’s all positive jealousy—‘I want to be responsible for creating something like that.’”

And, four years later, he would be.

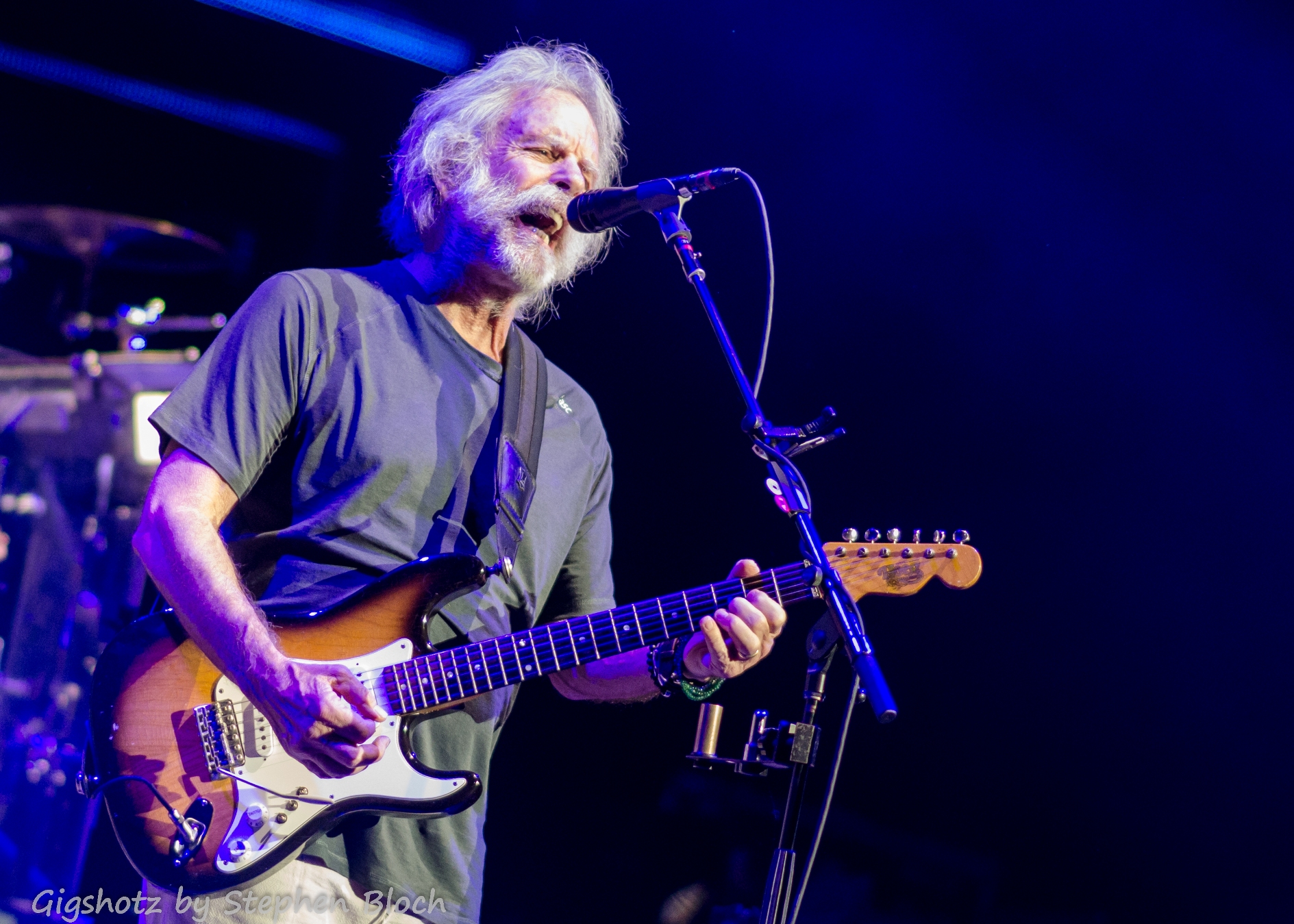

In mid-January 2015, the core four surviving members of the Grateful Dead announced that they would reunite to celebrate the band’s 50th anniversary. Mickey Hart, Bill Kreutzmann, Phil Lesh and Bob Weir revealed that they would return to the stage together, along with Trey Anastasio, Jeff Chimenti and Bruce Hornsby for three Fare Thee Well shows at Chicago’s Soldier Field—the site where the Grateful Dead performed their final gig on July 9, 1995. (They added two Fare Thee Well dates in Santa Clara, Calif., after the initial announcement.)

While the four Grateful Dead musicians had played together in a number of incarnations since Jerry Garcia’s passing in 1995, they had not done so since their July 4, 2009 appearance at Michigan’s Rothbury Music Festival. Over the intervening years, Lesh and Weir toured with their Furthur project, while Hart and Kreutzmann appeared together in the Rhythm Devils, rendering many fans apprehensive as to whether their collective musical paths would ever converge again.

Around the time of this announcement, Mayer was at Capitol Studios working on an album. Don Was, who had coproduced Mayer’s two previous records and was aware of his status as a newly consecrated Deadhead, invited him to attend a meeting in Capitol Tower with Hart and Weir. It was there, during Mayer’s first direct encounter with the pair, that he pledged his fealty to their music.

A couple of weeks later, Mayer was given an opportunity to serve as a guest host on The Late Late Show, during the interregnum between Craig Ferguson and James Corden. He invited Weir to join him for a performance, in which they teamed up on versions of “Truckin’” and an altogether apt “Althea.”

Their first musical exchange took place during soundcheck. As Weir recalls, “We had decided, more or less, which tunes we were going to do. So we rehearsed them but, two hours later, we were still playing. We had run the tunes and were still going at it. They finally just told us we were done and unplugged us.”

The musical connection was undeniable, leaving Weir to conclude that “the whole thing seemed like too much fun to run away from.”

While Lesh was no longer willing to commit himself to a steady road regimen at this point in his life, Weir was game. Hart and Kreutzmann signed on as well, with Mayer’s overarching enthusiasm holding sway.

“We weren’t looking for John,” Hart explains. “John came to us so impassioned that we couldn’t turn him down. It would be stupid. So we tried it out, and it worked from the get-go. He is really, really good—he’s fast and he’s confident. He came into this band knowing that it would be a great challenge, but he felt good about being a part of us. And we felt good about turning this solo artist into a groupist. So now he’s a groupist, and he really loves it too. There’s something you have to give up when you become a groupist. He’s normally a bandleader himself but, in this band, there are a lot of leaders. He has our sensibilities and he doesn’t have any of the pop-music trappings, as it were. We felt really good about him being a part of us, it was a very natural place.”

So in March 2015, before entering full-on Fare Thee Well mode, Hart, Kreutzmann and Weir spent a few days at a Bay Area rehearsal space looking to complete their lineup. The keyboard slot soon fell to Jeff Chimenti, who first joined Weir in RatDog back in 1997 as a Dead neophyte in his own right and has since appeared with him in The Other Ones, The Dead, Furthur and Fare Thee Well. Phish’s Mike Gordon was an initial option on bass; however, as he told last year, he decided to step back “because what I want to be doing with my time at 50 is writing and recording, and the Dead tour didn’t leave enough time for it. I hope I get to play with all of those guys again—and I hope they aren’t mad at me—because I have so much respect for them.”

Weir affirms that there are no hard feelings. He’s quite content that they were able to land Oteil Burbridge, fresh off of his 17-year stint in the Allman Brothers Band, who had some limited exposure to the Dead catalog, through his work in the Bill Kretuzmann Trio.

“Mike gave it a shot and it worked out pretty well,” Weir offers, “but then he decided he had too much on his plate, so we kept looking and we ended up with Oteil. And I’m glad that happened because Oteil is just a different style of bass player, so we can take the songs places that they don’t particularly go when we have a lead instrumentalist on the bass. It showcases the songs a little more and showcases the playing a little less.”

The Dead & Company name came courtesy of Mayer. “There are only so many iterations of Dead,” he explains. “I brought it up and it seemed right because it lives just between new and of course.”

The name stuck, even following a freewheeling group chat in which Hart, Kreutzmann and Weir spitballed some alternatives. “There were some incredibly wild suggestions,” Mayer remembers. “I’m a big fan of wild brainstorm sessions, but this is something wilder than I’ve ever seen. It was hilarious. But whatever name we were going to choose would have to be validated by the music. We could have called ourselves anything and, if the music was right, then the phonetics of whatever words we selected was going to sound right.”

In August 2015, Dead & Company announced a fall tour. Following the revitalizing vibe and collective catharsis of the Fare Thee Well shows, Mayer’s involvement (which had been rumored ever since the spring) was met with both optimism and skepticism.

Mayer was aware that some fans were leery of his participation but, to his mind, on some level, this was nothing new.

“When I was 16 years old, I would play these open-mic blues nights,” he remembers. “My friend’s dad would drive me to these clubs because he was the bass player. I would show up and everybody would be like, ‘Who’s the kid?’ I always knew I could answer ‘Who’s the kid?’ by the time I got offstage when they’d heard me play the music as best and as deeply as I could. Then, when I was 20 years old in Atlanta [after leaving Berklee College of Music], I entered an open-mic night, where it was all those older people wondering, ‘What’s going on here?’ I’ve never entered a room and people went, ‘I can’t wait for this. Who are you, strange boy? You’re probably great.’ It’s always been this grumble.

“I’ve been so weaned on people cranking their necks back and going, ‘What’s this going to be?’ that I wasn’t disappointed by the skepticism. I thought it was a healthy response. It would be insulting to the fans of this music to assume that they were going to very easily plug this dichotomous thing together and immediately decide, ‘Oh, yeah, it’s going to be great.’”

What many Deadheads did not understand is that Mayer treasures the Grateful Dead in the same way that they do.

“I listen to this music every day,” he explains. “I listen to it in the car wherever I go. It’s playing like nature sounds, the way you would hear a babbling brook. Grateful Dead music has a whole extra dimension for me than listening to music. There’s books, movies, theater, music, art, comedy, Grateful Dead. It’s a completely different lobe of my brain than music. I listen to this music to clear my head of music.”

“I see this canon of music as a city,” he adds in characterizing the scope of the band’s catalog. “If you put every Grateful Dead song together, it’s probably 12-square miles large and fully animated. You have ‘BrownEyed Women’ happening in this bar and, in back of that bar, later on tonight is ‘It Must Have Been the Roses.’ ‘Truckin’’ is on the highway and ‘Goin’ Down the Road Feeling Bad’ is on that highway, but on Sunday. You can just keep going and laying it in.”

He shares a few additional signature traits with the Deadhead community beyond this: As a teenager growing up in Connecticut, he made the pilgrimage to New York’s Wetlands Preserve and other clubs in the mid-‘90s to record Charlie Hunter and Medeski Martin & Wood.

“They called it acid jazz, and I didn’t quite know what the acid part meant because I wasn’t quite indoctrinated into the other stuff,” Mayer says of his taper days. “I remember seeing Charlie Hunter at Wetlands—it must have been Charlie Hunter Quartet when Calder Spanier was still around, and he was the saxophone player. [Spanier died in a 1997 auto accident.] I saw Charlie Hunter at the Middle East in Cambridge and brought this guitar pedal that he uses and had him sign it.

“I also had a DAT recorder with the external battery pack and this little lunch cooler that I used as my taper rig. I saw Charlie Hunter at South Street Seaport and I had the DAT for years. I learned all this playing of this one concert, and I learned to play like him as much as I could from all these DAT tapes that I made. After I went to the Berklee College of Music, though, I didn’t keep it going.”

Nonetheless, Mayer’s formative musical experiences in the improvisational realm were much broader than many Deadheads associated with him before seeing him in action. Indeed, before his first show with Dead & Company, many assumed that the group would gravitate back to the blues palette of the band’s early days when Pigpen exerted his influence. However, while Mayer is adept at such tones and techniques, he wanted to go the whole nine yards—or, rather, the full 12 miles.

“When I started, I looked at it from a completely technical standpoint. ‘Could I make this music happen?’” Mayer reflects. “There’s no reason to assume that anybody would know that I could, and I never held it against them. I feel that the steadfastness with which they protect the gate is the same loyalty once you’re in. It’s like the movie where there’s a bunch of seemingly scary biker guys, and a scrawny business guy endears himself to them in some way and they give him a jacket. If you do the work, if you can fix the guy’s motorcycle, you can get his jacket. If you compare my music to the Grateful Dead and that’s personified, then I’m the scrawny business guy in there. But I’m relishing the opportunity to do the work.”

The essence of the Grateful Dead experience is bifurcated. One side is that rich catalog of material. During the 1980s and 1990s, the mainstream media often questioned the vitality of their compositions. Most of these reports focused on the lot scene—in which every male Deadhead interviewed for a daily newspaper seemingly identified himself as “Jack Straw”—along with some dismissive remarks about improvisational excess. However, over the past 10 years, there has been a dramatic shift in critical reception, as official releases, a SiriusXM station and the band members’ ongoing efforts have framed the group’s work with new lenses. Outside projects such as the Day of the Dead tribute album have all served to affirm the vitality of the music, which always was at the core of it all.

Weir observes in this context: “People are starting to look at the songs the way that we have all along. Either we were ahead of our time or way behind our time—a bit one way or another. But it looks like it’s finally catching up. So now we have Dead & Company to reinvestigate those songs and see where they want to go.”

The material continues to evolve and reveal itself because the other essential side of the group is its experimental, exploratory ethos, which requires the band members to walk the collective fine line between being right and tight and liberated and loose. This is encapsulated by the way that Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann describe their performance style: Hart often refers to it as drumming without drumming, while Kreuztmann makes the point that, for him, drumming is not about keeping time.

The challenge and the glory of it all is that Dead & Company offers both a continuation and a new jumping-of point. Weir reinforces this as he notes, “Mickey and Bill and I go back a ways and Jeff and I go back a ways, but when you put the whole ensemble together, it’s a new band—it’s a new outfit.”

In comparing the group to Furthur, Weir suggests, “There’s a great deal of difference in the focus of the presentation. With Dead & Company, the focus is more on the songs and, with Furthur, it’s more on the playing. With Furthur, we started off a couple miles down the road from where the Dead left of because Phil and I both had a lot of miles under our shoes since the Dead played, and we brought that with us and we readily understood each other with that. We were ready to move on, whereas, with Dead & Company, we started close to where the Dead left off.”

So he instructed Burbridge to learn the last iteration of the songs performed by the Grateful Dead, focusing on 1992–1995. “In order for Dead & Company to make those tunes their own, it’s best that we go back to the original well,” Weir explains. “I envision this going on for some time, and the songs will continue to grow and evolve with new aspects and all that kind of stuff.”

Some of his intention is manifested in the mechanics of creating a setlist. At present, the band drafts it in advance; however, Weir aspires to return to the era in which, “typically, what we’d do was Jerry and I would figure out whose tune we were going to start with, and then we’d pick the first couple tunes of a given set and what we were going to close with. That was the extent of our set writing because everybody knew the tunes, so we could pull up whatever seemed appropriate at the time. And then, in the second set, we would do the same thing—just write the first couple of tunes and, oftentimes, we wouldn’t even get so far as to what we were going to close with. At that point, we’d just take it from go.

“Dead & Company is not quite there yet to where we can start relaxing and just working off memory and seeing what feels appropriate at any given point. But I’d be surprised if Dead & Company isn’t ready to do that soon.”

As for what happens in the moment, “Time is what you make it,” Hart explains. “You can think of the Grateful Dead as a rhythm snake: We expand, we contract, we go faster, we go slower. We’re constantly updating the groove to find the best possible feeling because that’s what we’re chasing. We’ve been chasing the feeling all our lives, and sometimes we catch up with it, and then we do our business in that groove. But it’s not necessarily linear; it’s not a straight furrow. It moves and it breathes, it expands or contracts—faster, slower, louder, quiet. It’s dynamic. It’s also a series of conversations. Bill and I have been having a conversation for 50 years, so what you bring to the table is really important because there needs to be two in a conversation. Whether it be with Bob, with Bill, or with John or Oteil or Jeff, there are all kinds of conversations going within the rhythmic structure of a band. Sometimes, of course, it goes into chaos, which is the way it’s supposed to. Chaos-order, order-chaos.

“The physiology of this whole thing is that Bill and I are driving the train along with the guitarists and everybody else. First, the conversation is with me and Bill. Then, we’re reaching out to both Bob and John, mediating the tempos and interacting with where they go—and they interact with where we go. In this band, you really have to listen because people are doing cool things all the time, and you want to pick up on the coolest of them. Then, I have a conversation with Bob, and Bill has a conversation with Bob, and then we’re there with John and Bob, and we try to set the record straight exactly where we want it to be. Once it’s there, then we just fly. The idea is coming to the place that we all agree is cool. It works, it feels great and everybody’s smiling. Then, you know you’re in the groove and you can do your business. That’s where you do the big business.”

Hart continues, “I’m in contact with Jeff because he’s on my side of the stage, and we talk all night. And then with Oteil—I stand on a vibrating piece of wood that has these motors on it, and I have Oteil coming through my feet. I can feel him coming up my pant legs. So I’m locked to him not just through my ears, but through my whole skeletal apparatus being vibrated. Same with Bill. I have Bill coming up—all the low end, the bass drum and all the stuff. I’m not hearing it, I’m feeling it as well. So, that really grounds you because you can hear and feel exactly what’s happening while this organism is being formed right in front of you. A band is just like an anthill: It swarms. That’s the goal: to get all together for one purpose, not individually, not thinking about you. It’s not you; it’s us.”

**

John Mayer’s fortuitous “Althea” encounter was by no means inevitable. When one is on a particular Pandora station, suggestions are generated not only through musical compatibility but also by a demographic component. In Mayer’s case, Neil Young is a generational peer of the Grateful Dead, which provides a nexus beyond the connective tissue of their song catalogs.

However, if one is listening to contemporary folk on the service, this will not necessarily lead to the complementary sounds of the genre’s iconic forbearers. Speaking from personal experience driving in the car with my teenage daughter’s Pandora app providing the soundtrack to our travels, we’ll often hear multiple songs by The Milk Carton Kids but nary a selection from Simon & Garfunkel. So too, Pandora steers us away from Workingman’s Dead or the all-acoustic Reckoning.

Mayer, who will turn 40 this fall, acknowledges, “Most of the time, it takes somebody to do something again for the new generation to find it. As an aging musician, you have to accept that there are better iterations of a design that still exist but that aren’t as popular as the current derivative version of it. But people want to participate in real-time with the artist. They want to know that the song they hear was written in the same air they breathe.”

To be clear, Mayer, is not referencing The Milk Carton Kids here, just the mechanism by which younger ears receive music.

“That’s just the way it is,” he continues, “and I have to imagine that, one day, when I have kids, my kid is going to run in the room and go, ‘Listen to this song.’ And I’m going to say, ‘You know that song is just like this other song but not as good. Let me play you this other song.’ And they’ll go, ‘No, not interested.’ There’s a certain modernity to it, where it doesn’t feel like it’s happening in their universe.”

When asked whether this perspective informs a certain missionary zeal that he brings to Dead & Company, Mayer responds, “Absolutely. That’s my nesting place in this. I think if I wasn’t looking at it that way, I’d be milling around inside this thing, trying to find a place to stand comfortably. The way that I have found to stand comfortably in this is I am helping to keep the portal open. I think that’s what people have responded to.”

“I get a lot of people’s feelings told to me about this music,” he adds. “They tell me how many times they saw the Dead and, then, they’ll talk about how this band makes them feel. And every time someone comes up to me and wants to talk about the Grateful Dead or Dead & Company, I just go into the most placid, satisfied, comfortable zone because it’s almost like somebody talking to me from a rotary club in some other state—‘Oh, we’re both in the rotary club.’

“But when they’re talking to me, they’re talking to one representative of this larger thing; they’re not talking to the guy who does it. My strengths as a musician are only coming into play as an assistant to the entire thing. For the first time in my life, it’s not about me doing the best this or the best that. I’m there as a brace that helps keep this thing open, so that people can get where they want to go. They’re not even really making eye contact with what I’m doing or with me. I’m there so that they can make eye contact with what they want to see that’s above all of us.

“They wish it was a different way,” Mayer adds. “We all wish it was a different way. We all wish it was the Grateful Dead, but what I think people have figured out is that, in many ways, you can still make it to that destination. You can still make it home.”

In late May, Dead & Company will begin their third round of “transportation work”: moving minds and elevating spirits. Their summer 2016 tour built on the momentum of their fall 2015 debut.

From Hart’s position on the drum riser, “I look out and the people are the same age. We’re getting older, and they’re still in their 20s and 30s. It flipped generations somehow; the music was passed on to another generation, and yet again, to another. A very unusual situation happened here where the music was vital, for many decades, and that’s because the brother passed it on to the sister, to the son and the daughter, and it became a good thing to do together as a family as well. That’s the power in being able to feel confident with your audience—that they’re really there for you.”

Weir has indicated a willingness to enter the studio with the group to record a mix of chestnuts and new originals, but there are no immediate plans. “I would like to do that with this band,” he affirms, “but right now, everybody has a bunch of commitments.”

Meanwhile, Burbridge explains that in his free time, “I like to check out as many different decades of the same song as I can for my own pleasure—just to see how Phil changed his approach, how the whole band in general changed their approach, how it all evolved over time. It’s amazing to see the different ways they approached the same song and I learn something from each one. So that’s really fun for me. It’s one of those things where you could look at it like it’s a lot of work, or you could just look at it like this enormous buffet where you have 10 different takes on bread pudding and 10 different takes on spaghetti and meat sauce, and you can’t do it all in one sitting. So the next day, you go back and try a different one.”

Mayer observes, “What Oteil brings is a sense of syncopation that really modernizes the band. He also brings the ability to respect the song but be himself. He and I being admitted latecomers gives us the perspective of having a lot of other influences by the time we got here, and the balancing act is: How do we represent our influences and how do we shape this music that’s been created over these many years? That’s an ongoing process. On the ‘15 tour, I was taking a bluesier approach to it and Oteil was taking a thunderous approach to the bass. Then, on the ‘16 tour, I remember having a discussion with Bob and Oteil, where he would bring the bass up to a bit more of the guitar register and I would bring the guitar a little further away from minor pentatonic blues into a more melodic thing. Bob and I have talked about this summer being the study of patience. When I listen to ‘77 Grateful Dead, and Jerry is playing this incredibly slow-thinking, mellow Zen guitar—it’s brilliant. It reaches this other level.”

“We’re still learning each other’s moves,” Weir suggests. “The music we play requires a lot of intense listening and a lot of experiencing it together. We’ve learned to play as a band and, the more we play, the better we get at. It is a work in progress, but we’re coming along.”

“When we first started with Dead & Company,” Mayer reveals, “I really wanted to get to a point where we could use the Stealie on a T-shirt. I thought it would be like being embraced if people could accept that the Stealie also meant Dead & Company. I have to reveal some total selfishness in that—‘Oh, my God, I want to be in this thing where we get to use the Stealie!’ But Bob, to his wisdom and credit, said, ‘Let’s earn that.’

“Then, by the time we went out on the summer tour I looked at the Dead & Company logo, and because of the way that we had played and because of the experiences that we had, I went, ‘No, that’s us. We did that.’ I think it’s a great testament to what Bob and Billy and Mickey put together to keep this spirit alive that by the time I was finally asked, ‘Do you want to put a Stealie on a shirt?’ it didn’t matter to me anymore because I realized we’re Dead & Company now.”