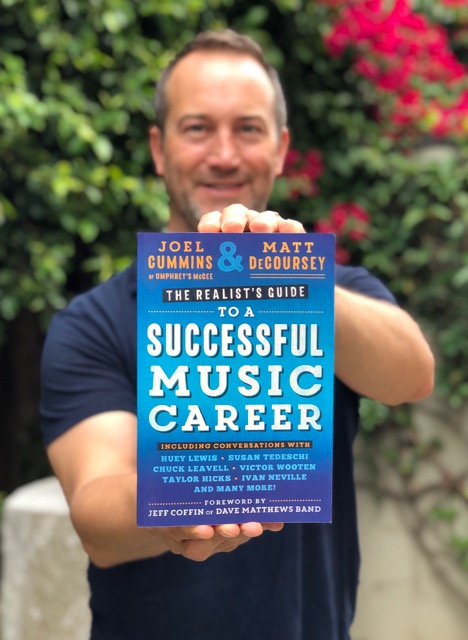

Behind The Scene: Joel Cummins of Umphrey’s McGee

“When Umphrey’s McGee started, I was the one managing and booking us,” keyboard player Joel Cummins explains while discussing the origins of his new book, The Realist’s Guide to a Successful Music Career, written with entrepreneur Matt DeCoursey. “I’ve stayed involved to an extent with that stuff throughout the band’s career. As a result, I’ve had a lot of artists ask me for advice, all across the board. I thought it would be a good idea for me to put all this stuff down because there are so many young artists out there who are talented, or have a foot in the door and are trying to figure out their next step. Of course, our first, biggest mistake was the name of the band. The second biggest mistake, three months later, was misspelling the name of the band on the spine of the CD.”

Beyond his own observations, Cummins’ book incorporates interviews with both musicians and music industry professionals, including: Huey Lewis, Susan Tedeschi, Victor Wooten, Chuck Leavell and Relix’s own publisher and multi-hyphenate Peter Shapiro. Cummins also speaks with Umphrey’s McGee bandmate Jake Cinninger, as well as managers Vince Iwinski and Kevin Browning. He explains, “I wanted to share my own perspective, but I also wanted to pepper it with all these other different experiences that would make the whole process a little less daunting for somebody who is trying to figure out where they fit into this world.”

Now that the book has been out for a little while, is there a particular topic or chapter that has sparked conversations or controversy?

The part of the book that has probably sparked the most controversy is the section about whether you can wear shorts onstage or not. That’s provoked a lot of really interesting conversations, with people sending me pictures of musicians in shorts, and me trolling people about wearing shorts. [Laughs.]

We have a rule in our band that you should not wear shorts onstage unless it’s above 90 degrees, you’re on a beach, you’re in a Jimmy Buffett tribute band, you’re on a punk tour or you’re Bob Weir. The example we gave was, “If Jeff Tweedy can play Bonnaroo in 95 degree heat with a jean jacket on [as he did in 2004], then you can ditch the shorts for a set.” If you’re trying to be taken seriously as a musician, then you should pay attention to how you are dressing. You should try to look a little more pro up there.

There are also a few more serious parts of the book that people have told me that they’ve really enjoyed. There was a very shocking moment when I was talking to Victor Wooten, who was very candid. He’d been on tour with the Flecktones, and they were doing really well. Then, he went out and did a duo or a trio tour for his album Show of Hands, probably back in ‘96 or ‘97. They were playing the Iron Horse Music Hall in Northampton, Mass. It’s a tiny little place and, at the end of the show, the soundman came up to him and said, “Hey Vic, here’s $25. Do you want to hold onto it or do you want me to hold onto it?” Victor told me that he assumed it was for a meal buyout or something. But, then, the soundman told him: “No, this is what we got paid.”

Victor said, “Immediately, I was furious but then I realized that I should have paid more attention to what was going on with management and contracts and everything because I would never have said we should do this gig. It was my fault that I didn’t know what was going on and, as a result, our band got paid $25.” That was a really important lesson: you need to know what’s going on with your business because you can’t survive and make art if you are always losing money.

That theme is at the crux of this book—the dynamic between art and commerce.

Yeah, when you’re in a situation where every dollar counts, that’s absolutely true. Our first tour manager, Don Richards, was famous for saying no every time you’d ask him something. [Laughs.] But there was a good reason for that: he knew we were on a very tight budget and he helped us really stick to that. Maybe in the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s, even the ‘90s a little bit, you could afford to be a little more of “the artist” and have this outside network taking care of things. But now the entire system is inundated with more people trying to create art than ever before. These days, it’s very hard to get someone to pay attention to what you’re doing and to care enough after they initially start paying attention to dive back into it again. That’s probably the biggest challenge out there. How do you make fans? How do you make people want to come back and see whatever you’re doing over and over again? That’s really the hardest thing.

The book is broad in its scope. I’m curious if there was anything you’d been thinking about for a while that immediately jumped out at you once you sat down to write.

The book starts with the most important question, which is the passion test. If you’re a solo artist, then you’ve got to have it yourself and, if you’re working with other people, then it’s something that everyone absolutely has to be on the same page with. You have to surround yourself with people who are so passionate about whatever it is that you’re going to create that they’re willing to say, “I want to do this regardless of if it becomes a career. I want to do this because I love doing this.” There are a lot of people in this business who start out with visions of grandeur but have misplaced priorities about why they’re getting involved in something, and those visions very quickly fade away.

Before you even get started, that’s a hugely important thing. One of the other crucial elements is surrounding yourself with people who you trust and people whose motivations are in the right place—people who are focused and driven, people that make you feel like you want to be a better musician. You want to work with people who are just good people, regardless of what you are working on.

One of the other challenging things is that, if you’re going to go out there and try to be a touring musician, then you’re only spending 25% of the time actually creating the music. You’re going to need to spend the other 75% with these people and that part needs to be an engaging and enjoyable experience—or that could also sink your ship.

Is there something in particular that struck you as essential during your interviews with these artists and industry folks?

Peter Shapiro’s story jumps out because he was just a huge fan of the Grateful Dead who had this specific passion for that music. I loved how it starts with him trying to produce a documentary about the fans of the Grateful Dead as a student at Northwestern University, and talking to people in the lots. He goes from trying to get some official statement from somebody in the band and totally getting shut down to, 20 years later, producing the largest Dead-centric event that has happened since Jerry passed away. Seeing that full circle thing should really give a lot of people hope about creating their own story and journey.

One of his most important bits of advice, which is also a recurring theme, is that you have to be out and meeting people face-to-face and creating relationships. So many of these things happen because you’re just in the right place. You obviously need to be at home working on music and doing your own thing too, but there should be an element of trying to connect with others.

I also love Huey’s story. I asked him: “What’s the most important decision you made early on?” and he said, without hesitation: “Finding my manager.” Bob Brown—who is still his manager today—found Huey and the guys after hearing them do this jokey demo of a song called “Exodisco.” They were hosting a comedy night on Mondays at this point—this was after his band Clover had broken up—and they had a disco version of the theme to the film Exodus. It is now on YouTube, so you can find it and give it a listen yourself.

Bob heard it, thought it was hilarious and tried to get into the club, but it was sold out. And he immediately thought, “Well, this is a good sign.” He got them a deal to record that song and then, with the additional studio time that they had to record, they made a demo of their other original music. They were being super crafty with what they had to work with to get started. You’ve always got to be looking at situations and saying to yourself, “OK, what are we not doing that we could be doing?” In that case, Huey was like, “We didn’t have much money, but we knew we had to record a demo. Once the engineer screwed up and said we needed more vocals on that one song, I told him, ‘We’re gonna need five hours of studio time to fix it.’ We went in there and did the vocals in 30 minutes and used the other four and a half hours to record our demo.”

That’s another great lesson: You have to get creative and there’s this element of not playing by the book in the music industry. You’ve got to make your own rules. That’s something that Umphrey’s has done, in a sense, with Headphones & Snowcones, which is basically handing out headphones to people at shows so that they can have a little more of a detail-oriented, personal experience. A lot of the things we’ve done have tried to use technology to create a more personal experience.

That’s our own twist on it, but there’s really that challenge to be out there and do something creative that people haven’t done before. In a way, that’s what is going to separate you from the pack of everyone else who is out there trying to do the same thing.

Peter believes very strongly not just in maintaining relationships, but also in doing so face-to-face. Has that been applicable to your own career?

Yes, and you can look at Umphrey’s McGee playing the Wetlands, which was Pete’s original club in Manhattan, which was really our introduction to him. What happened from that? We ended up playing the Jammys, which is where we met Huey Lewis and we got to perform with him, as well as Mavis Staples and Sinead O’Connor. That was this cool, surreal moment and now we feel like lifelong friends with Huey. He’s our buddy. We have Pete to thank for that. That relationship also led to us playing LOCKN’ Festival and the Brooklyn Bowls in New York, Vegas and London. And that led to us inquiring about going to Abbey Road, which is where we recorded an album. So all these little things led to different opportunities. Last time we played LOCKN’, Pete suggested that we link up with Jason Bonham and, this past year, we had Jason out to Red Rocks. It went well enough that Jason loved it and wanted to do it again. So Pete has been a catalyst for us to create more relationships just because of that exact spirit that he embodies.

This article originally appeared in the December 2019 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more subscribe below.