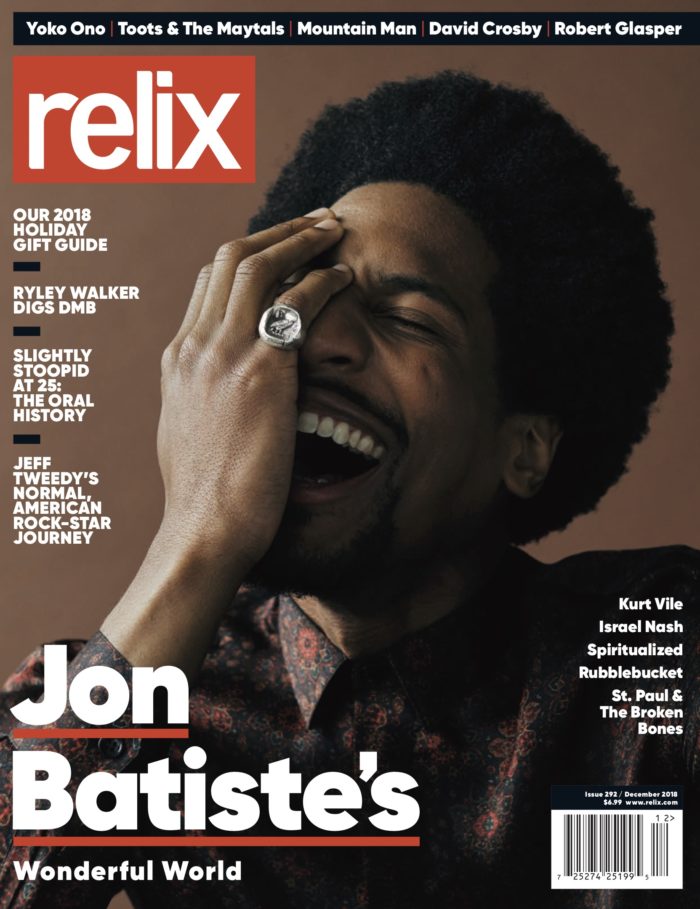

Jon Batiste: Man of the World

photo by Oliver Schrage

The major-label solo debut from Late Show with Stephen Colbert bandleader Jon Batiste surveys the sounds of his native New Orleans and beyond.

“I’ve come to realize the world needs more love. That’s what I try to do on the Late Show, with my own performances and when I’m making records,” Jon Batiste explains, describing his role as bandleader and musical director for The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, as well as his efforts with his group Stay Human and his major-label solo debut, Hollywood Africans.

“Every performer and every artist represents an emotion,” he continues. “If you strip it down to its barest form, each artist represents an emotion, or is giving people an emotion to help them, almost as an elixir. A lot of times, people look to me for hope. They look to me for a sense of joy and for a spark that they can ignite within themselves, whether they’re an artist or not.”

Batiste has been generating that spark since elementary school. He was born into a lineage of Louisiana-based musicians, joining his family’s Batiste Brothers Band at age 8. His father Michael, a bassist, co-founded the group with Jon’s uncles and the next generation eventually joined in, including older cousin Russell Batiste, Jr. (funky Meters, Vida Blue).

Although he initially focused on drums and percussion, Batiste moved to piano, while still a preteen, at the suggestion of his mother. His father then facilitated a deep dive into the instrument by steering the neophyte toward vital albums and contextualizing them.

“He would play Oscar Peterson and Sunny Stitt’s duo record for me [Sonny Stitt Sits in with the Oscar Peterson Trio]. I’d listen to it and be like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing. I can’t believe somebody can do that,’” Batiste recalls. “He not only played me those records, but he also showed me a connection since I grew up and played the same clubs as these musicians. James Booker sounded like four people playing the piano at one time and he recorded Spiders on the Keys: Live at the Maple Leaf Bar, which is where I used to play every week. In fact, when I was 14, Trombone Shorty and I co-led a band that is still his band today, Orleans Avenue. We played the Maple Leaf every week and a place called Café Brasil that no longer exists on Frenchmen Street.”

In 2004, the 17-year-old Batiste departed his Kenner, La. home for New York City, where he enrolled at Julliard and eventually received both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in piano. There, Batiste not only expanded his musical reference points—for one stretch listening to little more than Thelonious Monk—but he also founded the jazz-funk collective Stay Human. By 2013, Batiste was touring internationally with the group in support of their album Social Music, which eventually reached No.1 on the Billboard Jazz charts.

During this era, Jon Batiste and Stay Human even made a notable appearance at Relix for a cover of Miley Cyrus’ “Wrecking Ball” that continues to rack up YouTube plays. The video captures Batiste’s spontaneous decision to perform the tune, which he arranged on the spot, offering insight into his creative process. “That was a big song at the time,” he reflects. “I’m a big fan of hers and I had just listened to it. I love listening to songs as songs, not just the recordings—that actual song was a really good one that also reminded me of a blues lyric. I wanted to make it into that, and that idea just came to me at the time. I’m always having ideas, which is another great thing about the Late Show—I can follow my ideas and it’s never enough because there’s another show tomorrow. It’s beautiful to have the opportunity to do that. I just follow the spirit of the moment.”

Batiste’s Late Show gig was set in motion through his band’s memorable July 2014 performance on The Colbert Report. Five months later, it also yielded an invitation for Batiste to appear on the guest-laden final episode. He remained in touch with Colbert, who solicited advice on the musical direction of his future program, as he prepared to move from Comedy Central to CBS. These musings became formalized after Batiste agreed to come onboard and even write the theme song.

Batiste boils down his role on The Late Show to “contributing the love, the hope and the uplifting vibes of the music. That’s what I try to do in any setting, really. My goal is to always to keep it in a place of joy and humanity. My political views are rooted in the fact that people need more love. That’s really what all this is about—the right-wing conspiracy theorists and the super liberals all just want to be seen and heard. Everybody just wants to be seen and heard.

“Musically, it’s been amazing, the level of development that I’ve gone through in the last three- and-a-half years. I’ve had the responsibility not only to write music and arrangements for the band, but also to be spontaneous and turn on a dime, while figuring out how to play to the camera and also to the clapping, shrieking audiences. The range of different things I’ve learned to be able to do that aren’t musical, while playing music, has changed the way that I perform. Now, when I perform for a crowd of people who are just there to see me and hear my music, it’s almost like a cakewalk.”

Batiste has made time for such outside work with Stay Human and as a solo artist. This past summer, he closed out the Newport Folk Festival, leading a rotating cast through what was billed as “A Change Is Gonna Come.” His approach was “to have a lot of hope and a lot of joy on the stage to represent the historic, monumental moments that have happened at that festival and that happened in the ‘60s. I feel like we’re in a similar time where people are really called on as artists, not to just play music, but to have a message and uplift people.”

He was joined for much of the set by his summer touring partners The Dap-Kings, running through tunes like “A Change Is Gonna Come,” “Freedom Highway,” “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and “Ohio” (which Batiste, Leon Bridges and Gary Clark Jr. recorded in 2017 after receiving Neil Young’s blessing). This drew in guests such as Mavis Staples, Chris Thile, Brandi Carlile, Brittany Howard, Valerie June, Maggie Rogers and Preservation Hall Jazz Band, along with Bridges and Clark.

The Newport set also included “Don’t Stop,” the stirring ballad that closes Hollywood Africans. In late September, Verve released the album, which is named after a painting by Jean-Michel Basquiat, the subject of Batiste’s forthcoming Broadway musical. Hollywood Africans presents Batiste in an intimate environment, performing original songs and Crescent City classics under the watch of producer T Bone Burnett.

“The idea was to strip it back to me alone in the studio in front of the piano. I was talking with T Bone at Bono’s birthday party in 2013, about American music, history and all these different things,” remembers Batiste. “Then, by 2015, we decided to go in the studio in New Orleans and just do something basic, as an exploration, but I was not really thinking of making a record. And then in 2016-2017, the world changed. I went back for two more sessions and I felt like it was something appropriate to put out into the world right now.”

Your arrangement of “What a Wonderful World” on Hollywood Africans is more contemplative than the well-known Louis Armstrong version. What led you to approach the song that way?

I wanted to create a meditation on the lyrics that reminded us of the grandeur and beauty of this amazing planet that we live on and how much our problems are just a speck of dust in the timeline of eternity. We’re here for a short time and everything we’re arguing about and fighting about is really small in comparison to how long the planet has been here and will continue to be here, long after we’re gone. It’s something that doesn’t give people a solution to whatever they’re fighting for or up against, but it gives perspective so they can approach it from a more human place.

I feel that music like that and songs like that are rare to come by, so I wanted to transform “What a Wonderful World” into that. I thought the lyrics already represented that sentiment, but the music that surrounded Louis Armstrong’s version didn’t necessarily accent the lyrics in the way I wanted it to. I wanted to make it a meditation so people could listen to it and zone out into it.

“What a Wonderful World” is the second track on the record. It is quite a contrast with your original, “Kenner Boogie,” which opens the album in a much more spirited fashion. What informed that composition and why did you decide to lead off with it?

I’m from Kenner, raised in a New Orleans musical dynasty, and that sound is the original sound of rock-and-roll, which is piano or guitar imitating piano. Chuck Berry was imitating a pianist with his guitar. So it is not typical for that piano sound to lead off a modern record. It’s a 1950s rock-and-roll sound.

It’s particularly appropriate for what we were doing with this record, especially given that I come from the same lineage as these great musicians. So it’s carrying the torch and paying homage to them at the top of the record. I wanted to do that and also pay homage to the soil where I’m from. It’s just a tone that breaks it in, brings the light and gives you a chance to get set up for how emotionally deep the rest of the album gets. It’s almost like a decoy that leads you in one direction, then “Wonderful World” hits, and that’s almost like the real beginning of the record.

When you moved to New York and began attending Julliard, did the geographic or cultural distance lead you to recognize some aspect of your musical heritage that perhaps you had taken for granted?

I was just talking with Terrace Martin about this. He produces Kendrick Lamar, and we were talking about his time in New Orleans and how he saw the culture. He lived down there for a while with Snoop Dogg.

It was interesting to see how someone like him, who’s from the West Coast and comes from a very specific tradition of West Coast hip-hop and West Coast jazz, talking about the connection and influence New Orleans music had on him. He spoke about how rich the tradition is, especially the lineage of the Batiste family, and how the raw roots of American music were born in New Orleans.

I took that for granted, because I grew up around it. I moved out when I was 17 to go to Julliard and I’ve been in New York ever since. But Terrace was telling me, “Man, your family is a central part of the lineage of the roots of American music.” I didn’t see it like that at all. I was like, “Oh yeah, my dad plays bass, my cousins play instruments. It’s just something we do in our spare time in between basketball and chess.” So I did take it for granted and I didn’t originally think I’d be a musician; I was just playing because everyone in my family played. But I suppose by the time I was in New York and I had my own band and I was making money doing it and meeting my idols, I had become a musician. It kind of chose me.

Batiste at the 2018 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival (photo by Marc Millman)

Batiste at the 2018 New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival (photo by Marc Millman)

In many respects, mainstream American music has absorbed the sounds of New Orleans. Can you pinpoint a pop song or commercial setting drawn from that tradition but people might not realize it?

Absolutely. If you think about Drake and his song “Nice for What,” that song is heavily influenced by the New Orleans tradition. You can hear it in a lot of Drake’s music—the bounce rhythm, which comes from the bamboula rhythm. That’s at the root of all New Orleans music, from early second lines to bounce music. And if you think about it, Lil Wayne, who was a huge influence on Drake, grew up in the same places I grew up and experienced the same culture. On Lil Wayne’s latest album Tha Carter V, you’ll hear all types of New Orleans traditions.

People have been influenced by it across generations. Even now, Drake is one of the biggest artists in the world and one of his hit songs has a New Orleans rhythm. It’s amazing. People have been aware of it in a certain sense, but I don’t think they know how deep it goes. It’s really exciting for me to have that at the root of what I’m doing because I feel like I have been creating something from a perspective that’s very special.

Meanwhile, other people you grew up with are also sharing that tradition from their own perspective. You attended high school with Trombone Shorty [Troy Andrews].

Even before that, we went to a camp called the Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong Summer Jazz Camp, when we were preteens. He was among the first group of musicians, outside of my family, who I was inspired by.

I was also inspired by a lot of the elders—hearing guys like Henry Butler, Ellis Marsalis or Donald Harrison Jr. play live or talking to them and having them give me direction and encouragement while still being stern. Alvin Batiste was one of my greatest educators and mentors. [The avant-garde jazz clarinetist was a cousin of Batiste’s grandfather.]

But I’d also get a lot of my motivation from guys like Christian Scott or Sullivan Fortner, who I grew up with and who were developing at the same time as me. We were peers. Troy and I were really like brothers—we’d stay over at each other’s houses, trade records and do regular stuff too, like go to the mall. Then, as time went on, we’d do more professional things together. By the time we were 14-15 we’d be playing gigs. I remember we went to New York to play at the Apollo and play SummerStage when we were both 15-16.

Now, I look at everybody doing different things. I just saw Christian Scott and his band with Robert Glasper [R+R=NOW] at the Blue Note a couple of nights ago. It’s really cool to see what everybody’s up to. Sullivan is an amazing pianist. We used to be in the practice room together every single day at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, the high school we all went to. We would just be playing two pianos for hours at a time, just trading ideas.

Was your cousin Russell was an influence as well?

He was my oldest cousin, almost an uncle to me. He used to babysit me when I was a kid. I would go and sit on his lap while he was playing the drums when I was baby. Sometimes I would go to his house and even play in his band, The Orkestra from Da Hood, when I was a teenager. I would see how he would lead rehearsals. He’s such an extremely talented, genius of a musician. He’s very much an influence on me in terms of everything that I’m doing today. He enjoined me to figure out my voice and sound as a musician because he had such an original approach to the drums, but he’s also an original composer. When I was a kid, it was exciting to see how he put his music together in such unorthodox ways.

It was amazing just to be around that, and I loved the experiences I had playing with him. We did some stuff with George Porter Jr., and also with some members of the band Phish. Those were super fun experiences for me. There’s a great photo out there of me and Page [McConnell] sitting at an organ next to each other playing. Those experiences were great because the feeling that I had was that anything could happen at any moment. It can be exciting if you’re into that, although if you’re not used to it, it can feel like there’s no safety net. But I loved it.

With Stay Human, you’re well known for what you call a “love riot,” in which the band will lead a processional out of a venue onto the street. Can you talk about how this developed from New Orleans funerals and parades?

The love riot is the sound of catharsis. In New Orleans music, second-line music in particular, there is that spirit of unbridled joy. I don’t say “happiness,” I say “joy” because the thing about the second line, as opposed to the love riot, is it’s tied to different traditions. Whether it’s the Mardi Gras Indian tradition or the funeral procession, it’s tied to the different functions of life that happen in New Orleans. There’s music for everything in New Orleans, so that’s what the beauty of it is; it’s part of a bigger cultural occurrence. Whether it’s the death of someone in your family or the birth of someone or a Sunday dance or the Sunday traditional second lines or a Mardi Gras Indian ceremony or Mardi Gras, it’s always tied to something.

The love riot takes that catharsis—that sound of release and joy—and almost makes it agnostic. We can create the sound and that feeling anywhere; we can create this connectivity and love and community anywhere we go. We’ve done that across several types of venues, whether it’s playing in the subway or Dubai and Doha in the desert. We’ve played Carnegie Hall and done the love riot. You can do it anywhere. It’s not tied to a specific tradition, although it’s influenced by the culture that I come from.

What was the audience’s engagement and response in Dubai?

Back in 2012, into 2013, we did a long tour. It was about nine-months long or so, and we went to several different places. We went to the Middle East and Doha; we were there for about three weeks. We also went to Istanbul and did a love riot, and it was insane because you could feel the tension in the region. You could feel the tension from folks who weren’t used to that kind of expression, and you could also feel that the younger folks were all for it. It was really something special to see how people came together, even though there was a sense of danger around it.

When you first appeared on The Colbert Report in July 2014, you led the audience onto the street for a love riot. That was unlike anything that had previously happened on the show. Did you need to have a long conversation before you received permission for that?

By that point, I’d been doing it for years and a lot of fans who would come to the concerts would be waiting for the love riot. That feeling and that energy just came with us, so when we got the call to do The Colbert Report, that was a hard line for me. I wanted to do the show, but not if we couldn’t do our thing. We wanted to play the single at the time, “Express Yourself,” but we told them we’re going to need another segment to do the love riot. And they just said, “Yes”—it wasn’t even a conversation.

I was taking a hard line because I wasn’t familiar with The Colbert Report at the time. So I said to my manager: “If we can’t do the love riot, I don’t really want to do it. I don’t think it’ll represent the whole picture of what we do.” But they just came back immediately and were like, “Yeah, we’d love to do that.” The stars aligned; everybody got it. That’s kind of how it’s been working with Stephen ever since. We became friends after that performance. It was beautiful to see how his mind worked and to meet his team and crew before I worked with them on The Late Show.

When you were talking about Drake, you mentioned the bamboula rhythm, which played a unique role in New Orleans cultural life and beyond.

The bamboula rhythm is an African rhythm that goes back to the Congo. When slavery was happening in New Orleans, there was a place called Congo Square where the enslaved people could play and keep their traditions on Sunday, almost as a form of worship and communication. That was only allowed in New Orleans where it was able to sit and marinate, culturally. Congo Square was a unique place and, once slavery ended, that culture was instilled into the culture of New Orleans.

That’s a beautiful thing because, in all of the early music, whether it’s Jelly Roll Morton or Louis Armstrong or Buddy Bolden, you hear that bamboula rhythm. And if you go down the lineage, you continue to hear it in Fats Domino’s music, you hear it in The Meters, in the funk and soul of Allen Toussaint or Lee Dorsey or Harold Battiste, and you hear it in the rhythms of all the great jazz composers—Ellis Marsalis or Alvin Batiste or Henry Butler. That range, and how that rhythm has also gone into rock-and-roll, is incredible. To me, Fats Domino and Chuck Berry, two guys from the South, are the fathers of rock-and-roll. You can also hear it in Bo Diddley, that “I Want Candy” rhythm.

It originates from Africa, has gone to the Caribbean and Brazil and is a prevalent part of their folk music. So there’s a line that you can trace from New Orleans, which is, to me, the northernmost tip of the Caribbean, down to parts of South America and across the pond to West Africa. And you can trace the lineage of the bamboula rhythm if you follow that line. It’s kept its integrity over the years in a way that’s rare. It’s a really deep thing as an artist to realize and see how it manifests itself, even when you listen to the trends that are happening today—trap music is just African rhythms. And if you listen to trap music and you really dissect it rhythmically, it goes back to Africa.

New Orleans is a special place in that lineage because it was such an important port city at a time when all these different elements could blend and create a new culture—it was almost like a microcosm of what the world has become today. Over several hundred years, it became cemented into the culture in a way that, when I was born in 1986, those traditions were still alive. And that’s still true. My nephew is two years old, and he’s eating red beans and rice, and he’s going to the French Quarter and the French Market, and seeing the architecture from the Spanish and the French, and his great-grandfather is a Creole man from Lafayette who speaks French. These things are amazing. I don’t know how you’d explain it other than just divine timing.

“A Change Is Gonna Come” at the Newport Folk Festival, 7/29/18 (photo by Dean Budnick)

“A Change Is Gonna Come” at the Newport Folk Festival, 7/29/18 (photo by Dean Budnick)

The title of your new album is drawn from a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting. You’re working on a musical about his life, so I’m sure you’re immersed in his work, but how did you come to select Hollywood Africans?

It’s an homage to the great musicians and entertainers who gave so much to the world through their art. A lot of them had to deal with marginalization and oppression because people didn’t accept them for who they were; they had to wear a mask. That’s a lot of what’s being referenced in the Jean-Michel Basquiat painting. But I wanted to not only pay homage to that by framing the record with the title Hollywood Africans, but to also make a statement saying no amount of oppression or marginalization is going to keep the infinite power of the art that was put in that lineage—this lineage that I’m a part of—nothing’s gonna keep that from reaching the world.

Thanks to those musicians and entertainers, I don’t have to wear a mask. I can do my thing and express that, and share it with people across the globe. It’s a beautiful thing, and I thought it was a great way to frame the record because I’m tapping into all these superpowers that they left in blues and folk and jazz and R&B and rock-and-roll. I didn’t want to frame it as a retro project; I wanted to frame it culturally.

At the time, I was studying Basquiat for the musical, and I came across that painting and thought it was a really appropriate way to frame the music I recorded. It gives people something to dive into. If you’re not familiar with the work, then you can check it out. And when you listen to the album, I think it’ll give you an even deeper sense of what all that music means. It’s so heavy and amazing and profound.

In terms of the musical itself, how far along are you with that and what approach are you taking?

We’re still working on it. The great John Doyle, who’s an amazing, Tony-winning director—The Color Purple was his most recent piece on Broadway—is involved and the Basquiat estate, the Marks family, is producing. All of these different people who are involved are just looking to me to lead the creative on this and not only tell his story, but also share his art and give people that hope and, again, that creative spark of their own by coming to see the musical.

The timeline is not something we want to rush because we have so many resources at our disposal, given that it’s the first project the Basquiat estate has ever really given life to. There are so many different pieces of his artwork and notebooks we have access to that no one who’s done anything in relation to Basquiat has had access to in the past. It’s just a great opportunity for me to do something about an artist whose work has been an inspiration for me ever since I was 19.

When people think of Basquiat, a hip-hop, punk aesthetic comes to mind. Is that going to inform your music, or are you looking to make something broader?

His art and his approach are global. The new wave, punk and burgeoning hip-hop scene are all a part of it, but it’s so much bigger than that. Because of the Haitian and Puerto Rican lineage

he comes from—going back to what we were talking about with New Orleans, the Caribbean and Africa—all the different elements are essential in the context of how he’s been received as a black artist whose painting was just auctioned at Sotheby’s for $110 million. Framing all of that musically is bigger than just the early-‘80s and that’s exciting. It’s a rich, rich subject matter.

This article originally appears as the cover story in the December 2018 issue of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more, subscribe here.