John Simon: The Producer of The Band, Janis and Leonard Cohen “Vitalizes” His Career

It’s difficult to list John Simon’s accomplishments as producer. You can start reeling off titles such as The Band’s Music from Big Pink, their self-titled second album, and The Last Waltz ; Cheap Thrills by Big Brother And The Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin; Leonard Cohen’s debut album; Bookends by Simon & Garfunkel; The Electric Flag; The Child Is Father To The Man by Blood, Sweat & Tears … but after a while the names and the history surrounding them get a little overwhelming.

In the end, you have to stop and ask, “Really? The same guy produced all of these?” And the answer is, yes – and more. He has also written songs of his own, recorded a number of solo albums (with some very talented friends, as you might suspect), and plays a mean jazz piano. We won’t even get into his accomplishments in the worlds of television, movies, and on Broadway – then you’ll really be overwhelmed.

The point is, John Simon has been there and back – although up until now, he’s never talked a lot about it. That’s about to change, however, as Simon will be appearing at Joe’s Pub in New York City on April 25, debuting his one-man “No Band: John Simon’s Songs & Stories On The Road To Now” . (Details about Joe’s Pub and other upcoming gigs can be found here).

A blend of music and memories, Simon’s performances are bound to be entertaining – as was our recent conversation with him about the past, present, and future.

This is an impossible task, John – trying to cover your career in a single interview is crazy. It’s worthy of at least a three-part mini-series – (laughter) – or a book … which you should write.

You know, Brian, so many people tell me I should write one and who knows – I may sometime. But in the meantime, I’m just pulling memories out for these live shows like the one we have coming up.

Well, I wanted to ask you about your one-man performance at Joe’s Pub. What can folks expect to see and hear when they come for a night of John Simon?

It’s about 50/50: I’ve been writing songs all these years as well and I actually have people who are fans of those songs and come to hear them, so they won’t be disappointed. And then I know others will come to hear stories about the people I’ve worked with and have gotten to know, so they won’t be disappointed, either. It’ll be a mix.

To start with some of those folks you’ve worked with, I think it’s worth noting that as we speak it’s the one-year anniversary of Levon Helm’s passing. You were producer for The Band’s first two albums, along with being involved with The Last Waltz – both the album and the performance itself. How about we talk a little about some of your experiences with Levon and The Band?

Sure. Actually, I was musical director for the concert, but I wasn’t the only person who worked on finishing the record. My favorite part of The Last Waltz itself was at the dress rehearsal.

Really?

Yes, we were at the hall – Winterland – and I felt like the ringmaster at a superstar circus, you know? (laughter) I ran the rehearsal: “Okay, Joni – now you sing …” It was wonderful.

What a time! How did you first cross paths with The Band?

At that point, they were Bob Dylan’s backup band. When Bob had his motorcycle accident [in 1966] he put them on salary and put them up in a small house in Woodstock and they practiced in the basement. [In 1967] I was in Woodstock working on a movie called You Are What You Eat with Peter Yarrow and Howard Alk. Howard knew the guys in The Band and thought we’d be a good match.

Levon had just returned to The Band the day before I met them. When Dylan started using them as a backup band, he would do a solo acoustic set first and then do the second set with the full electric band. His diehard folkie fans were just so dismayed and felt betrayed because Bob had gone electric … and they booed. And Levon didn’t like to be booed.

He left and went back down South. When Levon showed up in Woodstock he’d just come from working on an oil rig in Louisiana.

He definitely was the real thing in so many ways. Do you have a favorite Levon story?

I think one of my favorite memories of Levon was when we both tried raw fish for the first time together. We had sushi out in LA at the Imperial Gardens restaurant next to the Chateau Marmont. He would often joke about that when he saw me: the time we took that courageous step to eat sushi together. (laughter)

John’s on tuba here

As well as producing The Band’s first two albums, you contributed musically, as well.

Yeah, I played a little bit. Producers come in different stripes; some are engineers, which I am not at all. People will ask me questions about what microphone I used for such and such and I have no idea. I’m a musician; I get off playing and contributing and arranging, you know?

Once I got involved with The Band as a producer, I started contributing my arrangement ideas. I was brought in on piano, say, when Richard Manuel thought the part was a little beyond him … and I was glad to step in.

At one point on the second album, everyone was switching instruments around on the song “Rag Mama Rag” . When Rick Danko picked up a violin to play instead of his bass, there was no bottom; no foundation. And that’s when they asked me, “You play tuba, don’t you?” (laughter)

And I didn’t, really- I play the baritone horn, which is pitched an octave higher and has a smaller mouthpiece and doesn’t take as much wind to blow it. But it was the same thing, really, so I could probably figure it out.

And you’re the tuba …

Yes, I played the tuba on “Rag Mama Rag” and it took all the wind I had. I actually got dizzy playing. (laughter) But it was wonderful to be part of it and I had a great time doing it.

There are so many great albums we could talk about, John. Another one that I think our readers would love to hear about was Big Brother And The Holding Company’s Cheap Thrills.

That was also related to Woodstock: Albert Grossman was the connection, as he was the manager for so many of those acts. I went out to the Monterey Pop Festival about the same time as I was getting done at Columbia Records, where I’d been working. I sort of hung out with Albert at Monterey and Janis was there – he just paired us up. It’s another fish story, actually … (laughter)

Go for it!

Albert and I flew out to Haight-Ashbury to meet with Janis and Big Brother And The Holding Company. We went to a Chinese restaurant that was one of Albert’s favorites and were seated in a back room for a private dinner. They brought out this huge fish – I don’t know what it was, but it had to be three feet from snout to tail. (laughter) The guys from Big Brother were fighting over who was going to get to eat the eyeballs.

And that was when I knew I was not in Kansas anymore. (laughter)

We’re lucky to have to film footage of Janis on stage that gives us a sense of her power and energy. What was it like to work with her in the studio?

Oh, man – she was a pisser. She was tough; she was really tough. I mean … I was recording two albums at once in adjacent studios at Columbia in Hollywood: I was recording the Electric Flag in the daytime and Janis and Big Brother at night. I was in the studio with the Electric Flag playing some piano on a song one day when Janis came sauntering in.

She says, “Hey, you!” – which is what she called me. “How come you’re playing piano on their album and you’re not playing piano on my album, motherfucker?” (laughter)

That was another affectionate name she had for me. (laughter)

Well, you were obviously someone special.

Yes – special. (laughs) But yeah – she was tough.

Another thing about the Cheap Thrills album: you know how sometimes things get printed and they become history even though they’re not true?

Sure.

Somebody printed that I didn’t put my name on Cheap Thrills because I was embarrassed about it or didn’t feel right about it or whatever. But that wasn’t true

The reason I didn’t put my name on it is because Howard Alk had convinced me in theory that “credit corrupts” – if you put your name on something, it becomes less of a pure piece of art and you’ll be wondering what people will think of it and it’ll affect your career from that point on. So we both made a pact to not put our names on the next project that came along … which happened to be Cheap Thrills for me.

People asked, “You don’t want your name on there?”

And I said, “No – credit corrupts.” (laughter) So it got turned around that I was embarrassed by the album, but that’s not true.

And subsequently I said, “Put my name on it.” (laughter)

So the early copies of Cheap Thrills didn’t have your name on them?

That’s correct.

Well there – there’s something for all you boys and girls out there in record collector land to look for: the early presses of Cheap Thrills that don’t have John’s name on them because he thought “credit corrupts” .

Yeah, yeah … (laughs)

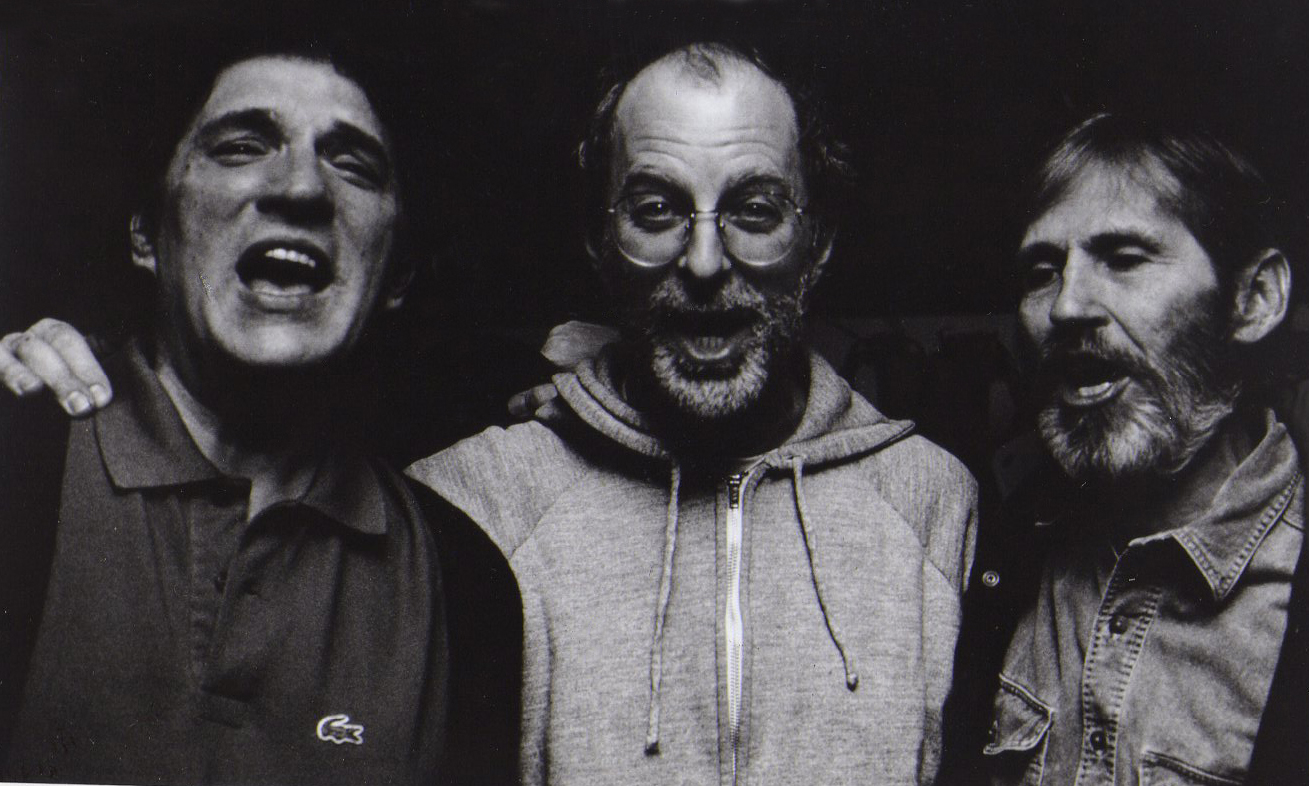

Flanked by Rick Danko and Levon Helm in 1991.

Do you think that one of the reasons why you had the success as a producer with so many of these artists is because you weren’t approaching things from the technical aspect?

I think that’s true. I’ve always been a musician and have always been interested in the musical end of things. People will write me fan letters and say, “I like your work” but they have no idea what my work is, you know? I have to stop and ask myself, “What have I done on these albums?”

I think one of the things for sure is that I’ve been a filter for the music that I’ve produced – to say, “I like this; this could use some work; I love this …”

But the thing is, it’s always been the artist’s album – I’m not going to force anything on an album that goes against the grain of the artist. I’m not a Phil Spector kind of producer who have their own sound that they want to hear … I’m at the artist’s service.

I was going ask you if there was ever an occasion where you tried to direct things in a different direction, but it sounds as though you’ve always let the artists be themselves.

Pretty much … I was producing at a pretty early age before I figured all this stuff out. There was one point when I tried to impose my musical will on an artist and she got so upset she let the air out of the tires of my car. (laughter) She will remain nameless – it was not Janis Joplin, or Mama Cass.

Oh, dear …

I’ve learned a lot since then. Now that I know what it takes to be a producer, I hardly do it anymore.

Is there someone who’s out there now making music that you would like to work with?

I’m sure there is, but I don’t know who it is. (laughter) I mean, I don’t keep abreast of modern music too much – I’ve gone back to what my real tastes are.

Which are?

I’ve always been a jazz lover. Every Thursday night for the past seven years now, I’ve been playing at a local joint with my jazz trio to keep my piano chops together. I call it my “jazz gym.”

*Super! Just for the record, I do remember when your first big hit as a producer – “Red Rubber Ball” by The Cyrkle – was on the radio in 1966. I was eight years old and I loved it. *

Well, thank you. (laughs) I loved it too, obviously. (laughs) It’s one of the things that changed my life. Columbia Records had just been folded into the corporate world of CBS. Prior to “Red Rubber Ball” , I had a little 10′×10′ office with no window. After it went to #2, they gave me an office with a window and a plant. (laughter) That was my first taste of success.

And a plant – you knew you’d arrived! (laughter) We talked about your tuba talents; how about some more musical contributions to other artists’ albums that you’re particularly proud of or fond of?

Oh … let’s see: going back to The Band’s first album, the rhythm underneath the intro for “Tears Of Rage” was something I came up with. On the second Band album, I loved the keyboard on “King Harvest” . Leonard Cohen’s first album: the arranging of the background vocals – I was really proud of that … Michael Franks’ “Tiger In The Rain” album … and then … ohhh … (laughter)

I know, I know … I won’t pursue this line of questioning. (laughter) How about your sessions as a solo artist – was it hard to make the transition from one side of the glass to the other?

Well, I’ll tell you – in 1969, Paul Simon came over to my house – I’d worked on the Bookends album with Paul and Artie Garfunkel. I played some of my songs for him and he said, "Hey John, you’re an artist " – and to hear that from Paul Simon was music to my ears.

That’s when I started thinking about making my own album, which turned out to be a lot of fun. I called on a lot of the people I’d worked with: Merry Clayton’s on that album; Richard, Rick, and Levon from The Band; a bunch of people from Delaney & Bonnie’s band: Carl Radle, Bobby Whitlock, Jim Gordon, and Delaney himself; Jim Price and Bobby Keys on horns; John Hall from Orleans … a lot of great people.

And who produced it?

I did. I mean, I always checked with the musicians playing with me to see if they were smiling … (laughter) That was one of the things I always liked: having other people in the studio and record as much live as I can. That’s the thing about the Thursday night jazz gigs I told you about: the way the trio is set up, I have to play with my back to the audience, but I’m facing the other guys in the band. I find I’m playing to them … we play to each other … and something wonderful happens when you do that.

It’s the same in the studio: musicians inspire one another and … and that’s when the magic happens, you know? After a point, perfectionism does away with that. It’s like having someone come in a year after the original track was done to overdub their part.

Who knows – maybe it sounds slick, but to me it sounds manufactured and … sterile.

I agree with you totally. Beyond the Joe’s Pub performance coming up, what can folks expect further down the road?

Well, I’ll tell you – the Joe’s Pub performance is really a big gig for me. I’d been content with my lot, playing Thursday nights and occasionally getting consulting work here and there. And then one day I received an e-mail – a fan letter – and I often get them from all sorts of folks who always say, “If there’s anything I can do, let me know” – but this one came from a manager, who said, “If there’s anything I can do for you …”

And I said, “Wow … sure!” So I sent him a whole list of things he could do for me (laughter), from a Carnegie Hall performance down to playing anybody’s living room at any time (laughter), which I’m always glad to do. And he said, “Well, let’s set you up in a venue in New York City, sell it out, and take it from there.”

So that’s kind of what’s happening … and I feel like a race horse that’s ready for the Kentucky Derby, Brian – I really do. (laughter) My wife C.C., who’s a lot of fun, has been directing me on this and writing a lot of my gag lines. She’s being a real trainer for me.

So to answer your question, I’m hoping I can go from there and do it someplace else, because it’s fun to do.

It’s great to hear that after all the people you’ve worked with and all the history you’ve been a part of, something like this is exciting for you, John.

You know, Brian, I actually looked at your website and I read where you said you’re married to your best friend – I’m the same way: C.C.‘s my best friend. When those solo albums came out in 1970 and ‘72, my wife and I had just gotten together. I was contemplating going out on the road to support the albums, but I’d seen what the road did to a lot of other acts and I loved the new relationship too much and I didn’t want to take a chance of sacrificing it by going out on the road.

So it’s actually incorrect for anyone to say I’m “revitalizing” my career – I never had one. I think I’m vitalizing my career. (laughter)

Brian Robbins vitalizes over at www.brian-robbins.com