Oteil Burbidge on The Allman Brothers Band Bassists: “Standing on the Shoulders of Giants (Berry, La

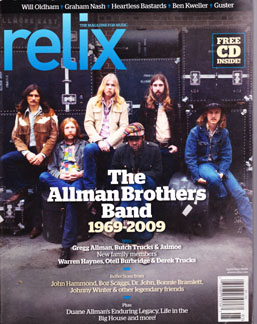

The Allman Brothers Band will continue their 2013 Beacon Theatre run tomorrow night in New York City. Since today offers a breather, we present this article from our April-May 2009 cover story on the Brothers, in which bassist Oteil Burbridge reflects on his predecessors.

It’s been a real honor, pleasure and challenge to hold down the bass for The Allman Brothers Band for the last 11 years. Fortunately I’ve had the rock-like shoulders of Berry Oakley, Lamar Williams, and Allen Woody to stand on. They were each so different from each other but they all possessed that combination of strengths that you need to be an improvisational musician. First, you need physical command of your particular instrument. Secondly, you need command of the harmonic and rhythmic traditions that you are dealing with, be it gospel, blues, jazz, bluegrass etc. Third, you need a strong sense of melody which is the beginning of composition, which is the beginning of improvisation. Most importantly though, is that personal fearlessness and humility that allows a musician to embrace his own uniqueness, to be himself in front of an audience, to reveal their true spirit. Most are lucky just to get just the first two.

Berry was a composer, not just a bassist. Listen to the basslines he crafted in songs like “Stand Back,” “Don’t Keep Me Wondering,” “Leave My Blues at Home,” “Every Hungry Woman,” “Melissa.” These are not just “bass grooves;” they are melodies that provide a groove as well as a counterpoint to the vocal melody. Like you see with McCartney and Family Man – it’s not even the same song if you change the bass line. Berry’s sense of melody and composition gave him the ability to apply the same concept to improvising. Berry Oakley was also a guitarist so he carried that mindset with him in his approach to the bass. In the spirit of the times he refused to accept the rules and traditional boundaries of the bassist’s role in music, and often departed from the normal path during the solos and jams. As Duane and Dickey developed their melodic themes in their solos, Berry was listening and responding with an equally spontaneous countermelody. They were like a flock of birds or a school of fish in their improvisations. Berry is the Book of Genesis for all bassists who want to learn about what it means to play bass in the Allman Brothers Band.

Lamar came more from an R&B and jazz background yet he still played with a pick in the ABB, with the exception of “Pony Boy” which he played on upright bass. He had that same great command of his instrument, understanding of rhythm and harmony, and sense of melody. Songs like “Come and Go Blues,” “Jessica,” “Southbound,” and “Can’t Lose What You Never Had” are testament to this. He tended to stick to the groove in long solos more than Berry. Butch says that Berry was more like a third guitarist, but of Lamar says, “When Lamar showed up, he was always at home, and you could count on him to be there. That freed me up to go away for awhile, and play what I wanted. I think it gave both Jaimoe and I more freedom on the drums, and allowed us to create more.” He also added a jazz feel sometimes that you’ll hear in songs like “High Falls” with its pronounced Latin jazz flavor. Some of Lamar’s more adventurous work can best be heard in Sea Level, a sideband that he was in with Jaimoe and Chuck Leavell. The important thing here is that Lamar played with confidence and command in the face of filling some extremely big shoes, giving much needed stability in a very trying time, and all without being a mere copy of Oakley.

Woody shared the same daunting task that Lamar did but times two (I don’t want to discount David Goldflies who is a consummate bassist, but all of the pre-Allen Woody songs that live on in our live shows today come from Berry and Lamar). Woody was such a force of nature that there was never any question that he would be a copy of his predecessors. God truly shattered the mold when he made Allen Woody. He has such heaping helpings of all those necessary qualities that I mentioned above. His personality was so much bigger than real life and that was truly reflected in his playing. He knew that on the one hand you had to be true to Berry and Lamar but that you have to put your own stamp on things or else it’s not really improvising, not really composing. Like Lamar, most of my favorite work of Woody’s is actually with Gov’t Mule. He was actually the hardest one for me to ever try to “copy yet make my own” when I had the pleasure of playing with Gov’t Mule. Technically I could do it, but the attitude… well if you knew Woody personally then you would know that it’s impossible to even get close. Woody’s spirit was so strong that you realize there’s a gaping hole bigger than you could have ever imagined after he was gone. If you doubt me then please direct your attention to exhibit A, the first 15 seconds of Gov’t Mule’s “Blind Man in the Dark.” The defense rests.

If I had to pick one word to describe the dominant feature of their roles in the ABB, Berry’s would be “revolution” for the way he refused to be bound by the conventional rules of bass, Lamar’s would be “foundation” for the rock-like musical stability that he provided when the band so desperately needed it in the wake of Duane and Berry’s deaths, and Woody’s would be “spirit” for the enormous injection of spirit that he gave the ABB when they needed it so badly to comeback after many years off. They were all complete musicians to me. They merged technique and a vast knowledge of their traditions and imbued it with their huge spirits. The proof of the size of their spirits is in the fact that 40 years later I am blessed to pay tribute to them nightly onstage. It’s all very humbling.

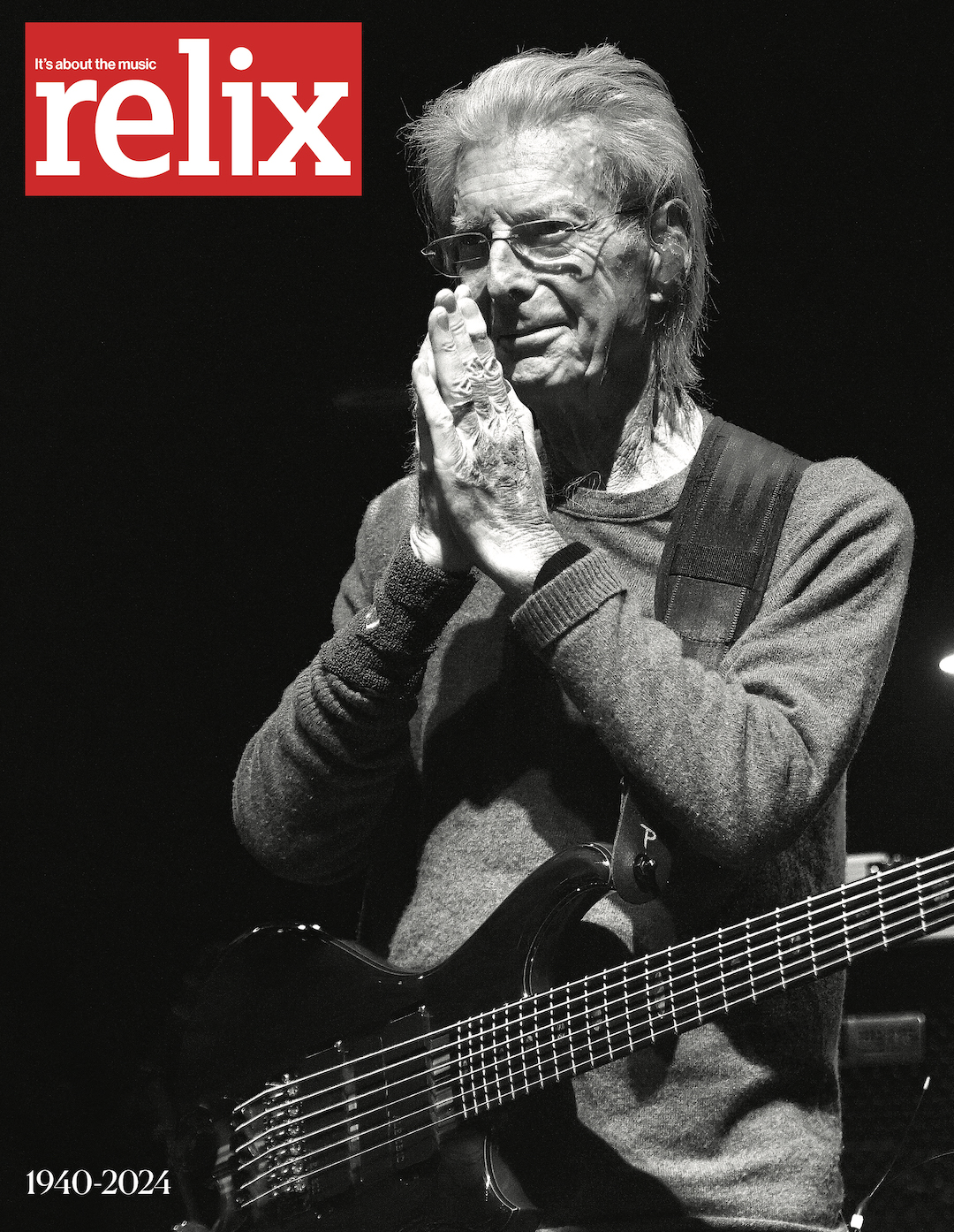

Oteil Burbridge joined The Allman Brothers Band as bassist in 1997.