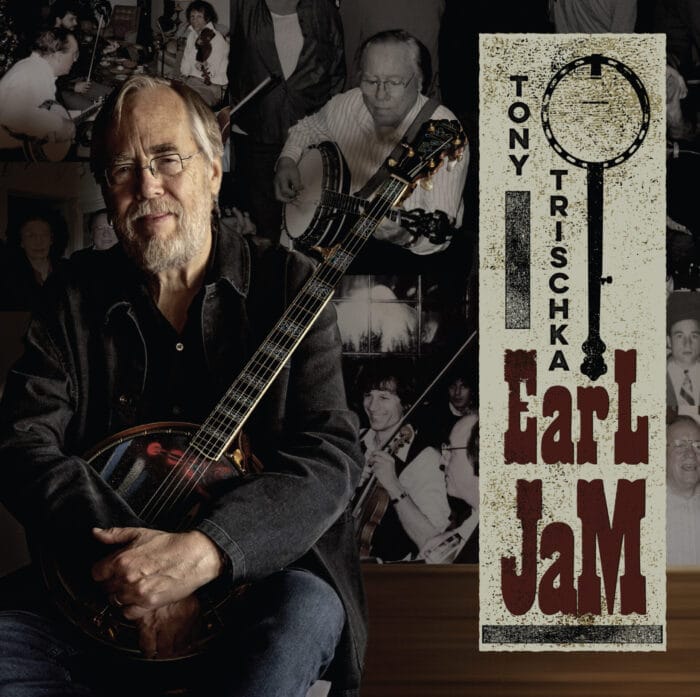

Tony Trischka Shares Earl Scruggs Solos Alongside Del McCoury, Béla Fleck, Sam Bush, Billy Strings and Molly Tuttle

***

It all began with a thumb drive.

Renowned banjo player Tony Trischka was helping fellow Earl Scruggs aficionado Bob Piekiel correct some transcriptions for a revised version of The Earl Scruggs Banjo Songbook when he received a gift that continues to resonate.

Trischka recalls, “While we were working together, he would email me a tune from these jam sessions with Earl Scruggs and John Hartford. Then, after a little while, he sent me a thumb drive with over 200 songs from the sessions. Most of them took place at Earl Scruggs’ house during a 10-year period in the 1980s and 1990s when Earl was sort of off the scene. John wanted Earl to keep his chops up, so he’d say, ‘Hey, Earl, let’s jam.’ Bob went to a few of these, and at some point, John Hartford got in touch with Bob and said, ‘Look, if my house burns down, all this music’s going to be lost, so I’m going to send you copies of all these cassettes.’ Bob eventually digitized them and sent me the thumb drive, which was one of the great blessings of my life.”

Trischka has been a Scruggs enthusiast since he began to play the instrument as a teenager in the mid-1960s. By the time Trischka started listening to the banjo innovator known for his signature three-finger style, Scruggs and guitarist Lester Flatt were near the end of their 20- year partnership, which began when they left Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys in 1948. Trischka notes, “My parents found me a teacher who actually was more of a folk singer than a banjo player and he tried to teach me claw hammer style, but that’s not what I wanted to do. Then I went to a hootenanny at Syracuse University, where my father taught, and these two guys got up there—one of whom was playing Scruggs style banjo. So I got in touch with him and started taking lessons. At the very first lesson, he taught me a tune in the Scruggs style and suddenly all these notes were in my hands. I was like, ‘Oh, my God, this is what I want to do.’”

Over five decades later, after listening to the songs on the thumb drive, Trischka had an idea that ultimately led to his new Earl Jam project. “I started thinking that these recordings may never see the light of day and people would miss out on all this music,” he says. “But if I record these tunes and play note for note what he played, then through me, people will be able to hear what Earl did. So my concept was to share this music with the bluegrass or banjo worlds, however small that might be, so that people who are nerdy like I am would get to hear exactly what Earl Scruggs played through my fingers.”

This began in the live setting with a show at Joe’s Pub in New York City. When Ken Irwin later heard the performance, he approached Trischka about recording some of the material in the studio. Irwin had originally founded Rounder Records in 1970 with Marian Leighton Levy and Bill Nowlin. Then, many years after selling it to Concord in 2010, the three decided to launch Down the Road Records, a new label with the same spirit as the original. Rounder had released over a dozen records with Trischka, and he was thrilled to work with the trio once again.

Earl Jam: A Tribute to Earl Scruggs finds Trischka recreating the solos from the tapes while performing with a variety of guest musicians, including Del McCoury, Béla Fleck, Sam Bush, Billy Strings, Vince Gill, Molly Tuttle, Sierra Ferrell and Michael Cleveland.

While this all came together, Trischka had another tool at his disposal, as he received copies of a notebook with a Mickey Mouse cover that currently resides at the Earl Scruggs Center in Shelby, N.C. “There in Earl’s own handwriting are 60 pages of his thoughts about his childhood, about joining Bill Monroe, etc.” Trischka says. “So not only do I have this much deeper insight into Earl’s playing from the recordings, but a much deeper insight into his life from these pages.”

Brown’s Ferry Blues

“Brown’s Ferry Blues” is a tune that I’ve always loved and Billy’s done it a few times, which you can see if you go down the YouTube rabbit hole.

I’ve known Sam since 1965, at the very first bluegrass festival in Fincastle, Va. I noticed this 17 year old playing fiddle off in the field and it was Sam. His groove is so deep, and his chops are so amazing.

I’d jammed a little bit with Michael Cleveland, but never really played with him. Béla was the one who said, “Let’s get Michael Cleveland on this.” It was a huge blessing to play with him because he’s so ferocious, so in tune, and his timing is impeccable.

Mark Schatz was another amazing addition. I think he was up in New England but he came down before he went back out to California.

One of the cool things is in the last verse, when Billy goes, “Well, here we are and here we are and here we are,” then he names everyone. That’s because I sent Billy the jam recording of that tune where, at the end, John Hartford forgets the lyrics so he lists whoever was in that jam. I wasn’t expecting Billy to cop that, but when we were in the studio and he did it, I was like, “Yessss!”

Béla and I are dear friends, and I asked him to produce this session. He was behind the board and there was space for another Earl banjo solo, which I’d had trouble transcribing because it was a little hard to hear. I was staying with Béla and he helped me finish out the transcription, but I didn’t have a chance to get it in my fingers, so I was going to overdub it later. Then I said, “Béla, you’re sort of good on the banjo. How about you take the solo and fill this last place?” [Laughs.] So he did and it was a remarkable solo. [In the liner notes, it’s identified as “definitely non-Scruggys banjo solo.”]

San Antonio Rose

We really wanted to have Sierra Ferrell on this project. I didn’t know her, but we reached out from a couple of different directions, and I called her up. I gave her a choice of five or six tunes from the jams that I thought would be nice for her to do and she chose “San Antonio Rose,” “Amazing Grace” and “I Still Miss Someone” by Johnny Cash, which will be on another album about a year from now.

She sings “San Antonio Rose” so beautifully. I wanted Darol Anger to play fiddle on that, and the day we were recording, I found out that my good friend Casey Driessen, who’s another amazing fiddler, happened to be in town. So I got them to do the double fiddle part. Then, at the end, we had Phoebe Hunt, who added something that’s not quite a yodel but makes you think of Bob Wills.

What I like about having “San Antonio Rose” second is that it starts with this very sparse banjo solo. So rather than having a whole album of just burning solos and lots of notes, it shows another side of Earl.

Chinese Breakdown

This is an instrumental that Earl never recorded. His playing is so deep and exciting on this one. He’s jumping all over the neck, playing notes that are not within three or four frets of each other. He’s going from the 12th fret to the fourth fret, which is a big leap. Whenever I play “Chinese Breakdown,” I get applause for that solo, which I play just about exactly note for note.

On this one, I have Stuart Duncan, one of the greatest fiddlers ever, Michael Daves on guitar and Dominick Leslie, a wonderful mandolin player based in Nashville. Everyone takes great solos and I take a great solo, which I can say without bragging because it’s Earl’s solo. [Laughs.]

My Horses Ain’t Hungry

Earl and John did two or three different versions and I liked that it had an old-time flavor, so I wanted have one tune on the album that recreated that. Here, it’s with me and Bruce Molsky, a dear friend of mine and an incredible old-time fiddler, among other instruments. He’s at the vanguard of old-time music—one of its greatest proponents—but he can stretch in different directions too, and I love his voice.

Plus, he was very close friends with John Hartford. So not to get too spiritual about it, but on some level, it seemed very appropriate to have Bruce represent that aspect of John Hartford on the album.

Roll On Buddy

They did “Roll On Buddy” in the jams, and I knew that Del had sung “Roll On Buddy” on Bill Monroe’s album Bluegrass Time. Bill was singing lead on it back then [1967] and Del sang with Bill. So I thought, “Let’s update this and have Del, as sort of the current father figure of bluegrass, fulfilling the same role that Bill Monroe fulfilled back then, now that Del’s in that position.” Still with great hair, as always.

Ronnie [McCoury] sings the harmony and it’s unbelievable. I’ve known them for years. I did an album in 1983 that Del and Ronnie played on when Ronnie was a teenager, called Hill Country. I first met Del in the late ‘70s, when I saw him at some country-music park in Pennsylvania.

This past January, there was a 100-birthday celebration of Earl’s life at the Ryman Auditorium. I was invited to be a part of that and Jerry Douglas, who was sort of the host, asked me, “What band do you want to play with?” I told him I’d take Del’s band because they’re on the album and we’d do a couple of those tunes. My rehearsal slot was at 10 in the morning, and when I showed up to play with Del and the band, I thought, “What a great way to start the day.”

Freight Train Blues

I’ve been really friendly with Dudley Connell for a long time. I always thought of him as a real traditionalist because the Johnson Mountain Boys would jump onstage in matching suits and string ties and do real straight-ahead bluegrass. Then I got friendly with Dudley and he said, “Oh no, man. I’m into The Beatles and James Brown.”

We’ve done projects here and there, and I thought he’d be great for this tune. Some people know this from Bob Dylan’s first album, but I went back to Roy Acuff’s version from 1936. It starts with the band slowly picking up speed like a train, so I decided to replicate that. It’s a fun way to approach the tune.

Casey Jones

In the ‘80s, our band Skyline opened up for John Hartford at the Birchmere in Alexandria, Va. I was talking to John afterward and he said that he’d just been at this jam session at Earl’s house and that Earl had played “Casey Jones.” I’d never heard Earl play “Casey Jones”—it’s not on any recording—and I asked John if he’d play it for me the way he remembered Earl playing it. He said, “Something like this,” and he did it in drop C tuning.

Then when I got these jam sessions, there it is, except Earl does it in a completely different tuning—regular G tuning—which means he had two completely different ways of playing this tune. I thought it was cool that he could do that.

Dooley

I’ve known Molly since she was a teenager. I was invited to teach at Shasta Camp up near Mount Shasta in Northern California. There was one banjo student and three of us who taught banjo, so we all taught one lesson to this young lady, who was a really good Scruggs player. That was Molly Tuttle.

I didn’t even know she played guitar at that point. Then she was living in Boston and I do this Christmas show every year—I’ve been doing it for about 26 years—and she did two years with me, one of which we recorded at Levon Helm’s barn in Woodstock. So we go a long way back and I wanted to have her on the album because she’s such a great singer and player.

I gave her five or six choices of tunes to do, and she chose “Dooley” and then “Red River Valley,” which will be on the second album.

Cripple Creek

One of the things Earl said in these writings from the Mickey Mouse notebook was that when he first started, before he was playing with people, he would play one song for 10 minutes. He’d be sitting around by himself at home on the porch of his rustic house in Flint Hill, N.C., and he could play a tune as long as he wanted. But then he started playing with some local musicians, older guys, and he could only play one or two solos in the tune. He couldn’t stretch out, which frustrated him a little bit.

He also said that the people he was playing with looked very serious when they played and it sort of bothered him because he thought, “You’re enjoying playing music; you should be smiling when you’re playing.” That’s when I realized, if you look at the old videos of him from the Martha White shows in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s that you can find on YouTube, when he takes a solo, he looks out at the camera and there’s almost always just a little bit of a smile on his face.

The thing that blew me away about “Cripple Creek” is there were four or five versions of it at different jam sessions at different times. On a lot of them, he played close to what he had played on Foggy Mountain Banjo, which is the all-time great banjo album. But on this one version of it, he took this highly syncopated, bluesy solo, and it blew me away. I thought, “This is amazing. It’s not a blues tune, it’s a fiddle tune and he just wanted to play this blues thing.”

That’s why I had to record “Cripple Creek,” so that people could hear it. Dudley sings it and he has to go pretty fast to get all those words in. Then he finishes with, “I’m going up to Cripple Creek to see Old Earl” rather than “to see my girl.” He threw that in and it was a great moment.

Amazing Grace

It’s such an amazing song, and similar to “San Antonio Rose,” what I love about it is it’s much sparser than what he usually does. It’s just the bare-bones melody for the most part, and it’s so beautiful, which shows that you don’t have to get all fancy with it sometimes.

We did it with Sierra and the band, she sang it beautifully, and I thought, “OK, that’s it.” I hadn’t thought we should do anything more to it. But then Ken Irwin suggested the McCrary Sisters, a gospel group whose father [the late Rev. Samuel McCray] started the Fairfield Four. So I reached out to them and they said yes. They were amazing, wonderful and fun, and they just knocked it out of the ballpark with their backup singing.

Lady Madonna

I wanted to do some things that people might not have heard Earl do before. He never recorded this but he played it with the Earl Scruggs Revue [which featured his sons Gary and Randy.]

Earl continued to evolve. After he and Lester Flatt broke up, Earl put out an album called Nashville’s Rock, and on the back, he’s standing in front of a bank of Fender amplifiers and they’re doing tunes like “Hey Jude.” When Lester Flatt put out his first solo album, it was a much more traditional album. One of the songs on there was “I Can’t Tell the Boys from the Girls.” The lyrics then go, “And friends, it’s really messing up my world/ They all wear long hair and bouncy curls.” So they were going down different paths.

Here, I had Jacob Jolliff on mandolin and Michael Cleveland, so I said, “Let’s just jam out at the end.” The playing is ferocious—what Michael and Jacob do on that, it’s just ridiculous.

Bury Me Beneath the Willow

I would give people a few choices, and Vince Gill wanted to do “Bury Me Beneath the Willow.” I’d met him when he was in Pure Prairie League in the ‘80s. Our band Skyline played at this festival in Milwaukee, and they were on the bill, so we went backstage for a quick shake and howdy.

I think Ken Irwin suggested him, and when I called Vince up, he said, “Hey, Banjo Man.” I barely know the guy, but he immediately put me at ease—he was so friendly, warm and fun. This session was at noon and I figured I’d show up 15 minutes early but he was already there. He got there half an hour early. That’s Nashville time—15 minutes is too late to show up early. You need to make it half an hour early. [Laughs.] So I’ve taken that to heart whenever I can.

Vince did an incredible job on it. I also had Brittany Haas on the session, along with Dominick Leslie and Mike Bub. Then I decided to add Michael Cleveland in post-production, as they say, because I decided I wanted a double-fiddle break for a real heavy-duty bluegrass sound.

“Bury Me Beneath the Willow” is a really sad song, so when I got Michael into the studio, I also asked him to play a more atmospheric solo at the beginning. What he did was achingly beautiful.

Shout Little Lulu

I love this because it’s one of two solo tunes that I’ve found on all these recordings—the other being “Boil ‘em Cabbage Down,” which is going to be on the second album.

On “Shout Little Lulu,” he’s just sitting around talking to John and he says something to the effect of, “This is a tune that I used to play at square dances when I was very young, when there were no other musicians.” It’s in drop C tuning and it’s fairly straight ahead, but it’s just beautiful. What really knocks me out about it, is assuming that what he played in this jam session was similar to what he played when he was 13 or 14 years old, it’s the earliest example of what he was doing.

The earliest recording we have is from 1946 or thereabouts, which is “Heavy Traffic Ahead,” the very first tune he recorded with Bill Monroe. That was the first time Earl went to the studio. There are no recordings before that, but at least with this, it’s probably the earliest example of his playing. It may not be exactly note for note, but I think it’s a really important tune to have on there.

Little Liza Jane

This is a great old fiddle tune and I really liked what Earl played on it. There’s one place where it sounds like he meant to get up to the eighth fret on the second string, but he missed it by a fret—it hangs on the seventh fret. Rather than immediately switching to the eighth fret though, he stayed on the seventh fret for a couple of rolls. When we play out live, I do that because I think it’s so cool. It sort of creates this tension. He’s not quite getting up to the tonic note, he’s just nibbling at it one half step below that.

When we recorded it, I had Mr. Bass Man himself, Mike Bub, and Brittany Haas, one of my all-time favorite fiddlers—I always talk about her bionic bowing arm. We also had Del in the studio this day. I asked if he wanted to sing on it, and he said, “OK,” because Del’s so obliging. So I got him on a third song, and he’s way at the top of his range, just killing it.

Amazing Grace – Postlude

On this take of “Amazing Grace,” I thought we had finished but Sierra spontaneously started clapping and made one additional run through the verse. It felt like a perfect outro for the album.