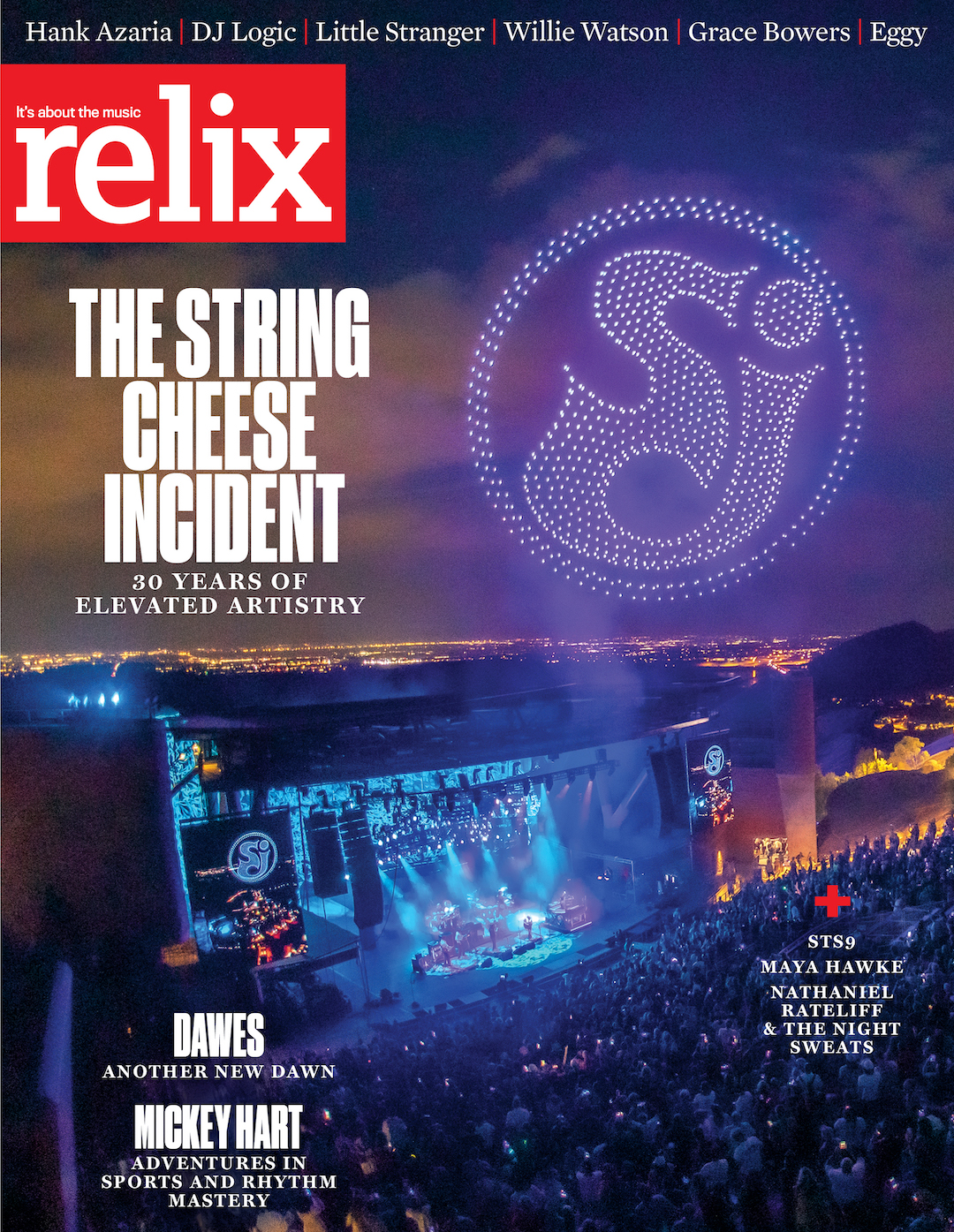

Ron Rakow on His Early Days Documenting Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead

(© Ron Rakow/Retro Photo Archive)

**

The cover of the current Relix features a photo of Jerry Garcia taken by Ron Rakow, while the Grateful Dead were recording their debut self-titled record in 1967. It is among a treasure trove of images that has been tucked away in Rakow’s garage over the past few decades.

Rakow was a Wall Street arbitrageur, who relocated to San Francisco in 1965. He would become part of the Dead’s management team, helping to create the band’s record label, before leaving during a period of tumult a decade later. His initial connection with the group was facilitated by his love for photography, which he explored during his years with the band.

He credits Garcia with supplying confidence during a moment when he started to doubt his camera work. “It took me a lifetime to get good with numbers and deals. I went to college for it,” Rakow recalls. “I wasn’t sure about my photos but Jerry told me early on, ‘Don’t be insecure. I will guarantee you this, if you like it and I like it, then it’s a good picture.’ I didn’t have that much faith in my own ability to judge, but I had 100% faith in Jerry’s ability to judge. So I used that as an operating principle.”

Thinking back on this era, Rakow also fondly recalls a conversation between his father—who worked in the garment business—and Garcia.

“He made ladies clothes and his business was a mile away from the Navarro Hotel where we were staying,” Rakow remembers. “So he came down because he wanted to meet the band and figure out what I was doing. I remember he shook Jerry’s hand and said, ‘Garcia, let me ask you a question. Why do you play so loud?’ Now that kind of question could elicit a sarcastic answer, but that wasn’t Jerry, who said to my father, ‘You know Mr. Rakow, we live in a society that has so much bullshit and it’s coming at you a mile a minute. The only way to stop it is to overwhelm it. That’s why we played so loud.’ Later, when my dad left and we took a cab to his house in Brooklyn, he said, ‘You know, I thought you were wasting your time with these guys, but that Garcia is a really smart guy.’”

Rakow adds that Pigpen had slept through the encounter but requested to meet Rakow’s dad the next day. “So we jumped in a cab and after introducing Irving Rakow to Pigpen, my father said, ‘What did your mother call you?’ Pig says, ‘My mother calls me Ron.’ So my father said, ‘Would you mind if I called you Ron?’ and Pigpen said that was fine. You see my father was a religious Jewish guy. He couldn’t call somebody Pigpen because that’s traif.”

Rakow had entered the Grateful Dead scene after setting up an office on Lombard Street where he partnered with a brokerage firm on a financial project. However, during early morning archery practice at a nearby installation, he had struck up a friendship with a pressman at the San Francisco Chronicle named Speedy, who in turn, talked him up to Grateful Dead managers Rock Scully and Danny Rifkin. They paid him a visit one day to gauge his interest in rock music and assess whether he might wish to work with them.

Rakow recalls, “This led to a meeting with Augustus Owsley Stanley III. It turned out the day he came, a package arrived from B&H photo supply store in Manhattan. It was a Hasselblad camera with an extra back where the film cassette goes, so you can go from black and white to color or whatever. I had become interested in photography to take photos of my kids. Owsley was so impressed with this talk where we didn’t even mention the Grateful Dead or music or the rock-and-roll scene, that he went back to the Dead and said, ‘This is the guy.’ So now the band wanted to meet me.

“They were playing someplace on Friday, so I go there and somebody gives me a Pepsi Cola. Well it didn’t happen immediately, but after a while I felt that my respiration was matching the respiration of the little backstage room we were in. This is while I was talking to a guy named Garcia. I had never heard of him before but he was clearly a smart guy and a very nice guy, although he asked me a question that absolutely fractured me. He wanted to know if there were no such thing as money, how would I provide for my family. Once I determined that he wasn’t fucking with me and that it was a real question, I gave him as real of an answer as I could. I told him that my one talent aside from making money was taking photographs. So I would find a group of people who were wealthy and curious and wanted somebody to go to the world’s hot spots and come back with the truth—words and pictures. I told him I thought I could do that better than anybody. Then he said to me, ‘If you mean it, if that’s true, the world is going to be at the foot of our stage, and you can take a lifetime worth of pictures.’ Well, I closed my office two days later.”

How did the rest of the night go given the Pepsi and all?

That material was made by Augustus Owsley Stanley III, so it was the real deal. The second set was about to start, so I walked to the front of the stage, took off my corduroy jacket, rolled it into a ball and lied down on the floor right in front of my new friend Jerry Garcia. I had never heard him play his guitar before.

Then all of a sudden they started playing a really simple song in 3/4 time. It was about a guy who went to jail and was alone in the world, then all of a sudden he got a letter. So he answered it and he sent his answer in the mail by air, which proved “I have a friend somewhere.” [i.e. “Viola Lee Blues.”]

Anyway, I’m lying on the floor at this guy’s feet and all of a sudden at the end of a run of 3/4 time there were five guys with loud instruments who went apeshit. I don’t know what else to say. They were so loud and so discordant that I could not formulate a thought.

I have lots of theories about living and one of them is that life is a dance between order and chaos and neither side can win. But in that moment the world was ending because chaos was, in fact, winning. That’s my principle. If either side wins, life is over.

I’ve run through this in my mind many times, but no matter when I talk about, or when I think about it, it has an unbelievable effect on me, just like it did there. Chaos was clearly winning while I’m writhing on the floor with my head on my corduroy jacket. Then all of a sudden, the music stops. It doesn’t get low, it stops. There’s a hole in it, like a cavity. Then it’s back to 3/4 time and “I got a friend somewhere.”

I opened my eyes and at the very tip of the stage with his shoes over the edge was my new friend who was looking down at me laughing. He had asked me that question earlier, “What would you do if there were no such thing as money?” “I’d be a photographer.” Well, now I’m a photographer. End of story.

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think back on shooting the Grateful Dead as they were recording their debut album?

Danny had said, “There’s going to be pictures, so why don’t we weave into the deal that Cadillac Ron will go down there with the band to the studio?” By this time Jerry had named me Cadillac Ron.

However Warner Bros. responded, “We are not paying any more money. If you want a photographer in there, you pay him.” So I said to Danny, “Tell them we’re going to pay the guy and then ask if he can have a purchase order for the film.” This way the Warner guy would have a win, even though it only would have been a hundred dollars a day.

The guy was Mo Ostin, the Chairman of Warner Bros. and he agreed, but I still felt fucked over. I certainly wasn’t going to charge the Grateful Dead a hundred dollars a day for my time. This was part of my job. We all got paid the same thing— room and board and $5 a week. I always roomed with Pigpen and I would take acid while he would drink Southern Comfort. The $5 a week meant that if you smoked cigarettes, you could buy a carton of cigarettes. Jerry and I both smoked Paul Malls and we wore Levi’s. So in one week you could buy either Levi’s or cigarettes. You could never buy both.

So, when I went to the photo supplier I had a score to settle with Warner Bros. because they cheaped out. I drove there in my Cadillac with the purchase order and I got so much film that I still have some today. When I was done filling the trunk you couldn’t get a cart of cigarettes in there and I went back six or seven times. Nobody called to check because I had it in writing. Mo Ostin and Joe Smith talked about that for 15 years. They would relax around the Grateful Dead until you mentioned Ron Rakow.

**

Ron: I took this at Columbia during the summer of the student riots. We smuggled the Grateful Dead’s equipment into the quadrangle. The musicians walked in but everyone else pushed these cases with wheels on them from four different places.

We all met up at the student activities department that did the events. Then we plugged in and, all of a sudden, it turned out that this wasn’t just a bunch of random guys, it was a rock-and-roll band. The students saw it and the cops that were keeping people out of the campus saw it, but they couldn’t get through the students. Before they could even react, the Grateful Dead played “Dancing in the Streets” and you cannot listen to the Grateful Dead play “Dancing in the Streets” without movement. You cannot. They could use that as a cure in hospitals because you’re not going to be able to stay still. I couldn’t, anyway.

The Grateful Dead played the way they did for almost four hours. And when the Grateful Dead left the stage, everybody left. The only ones still there were the cops who all had flowers sticking out of their pockets. About a third of them had their hats turned sideways, too. The riot was over.

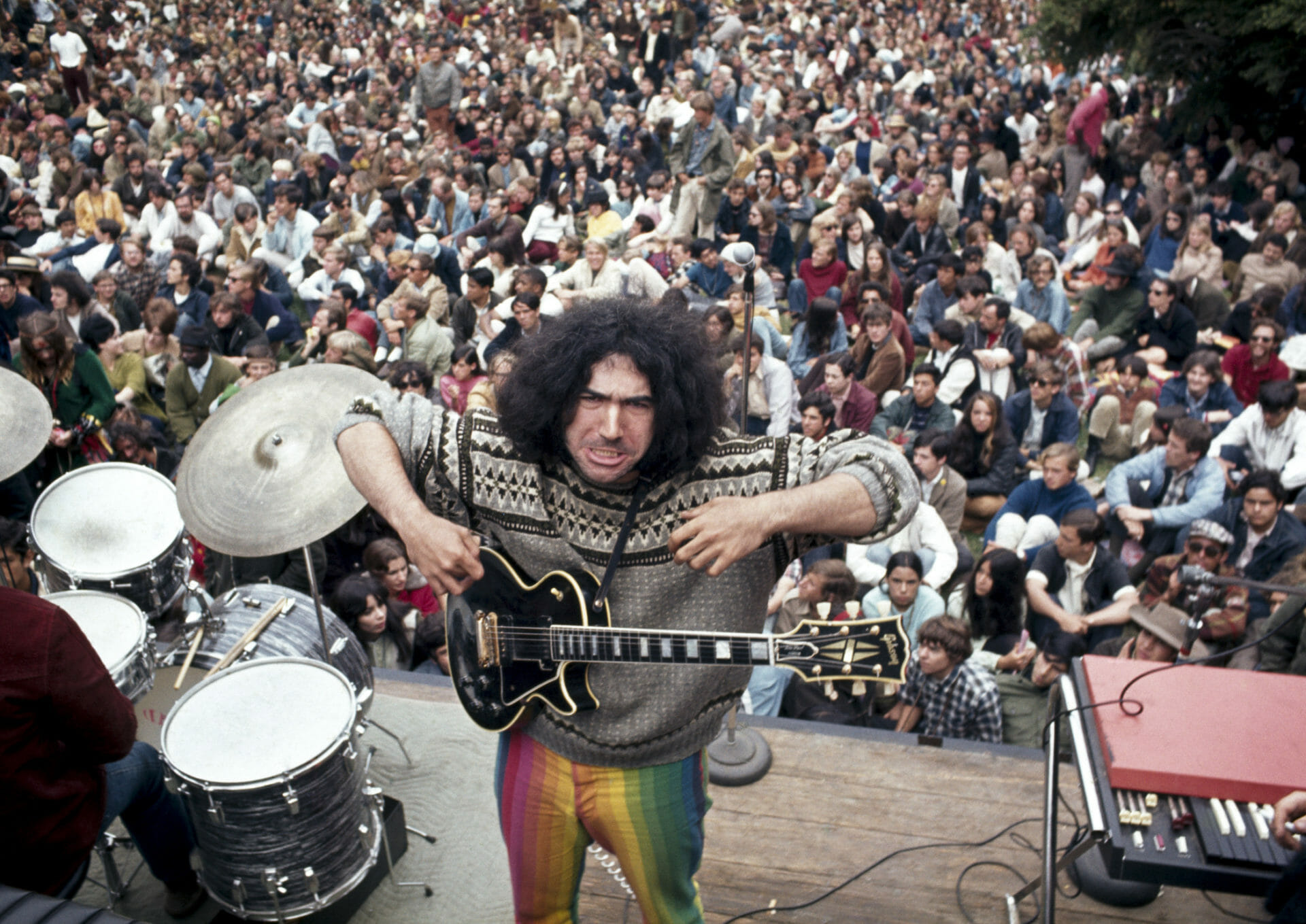

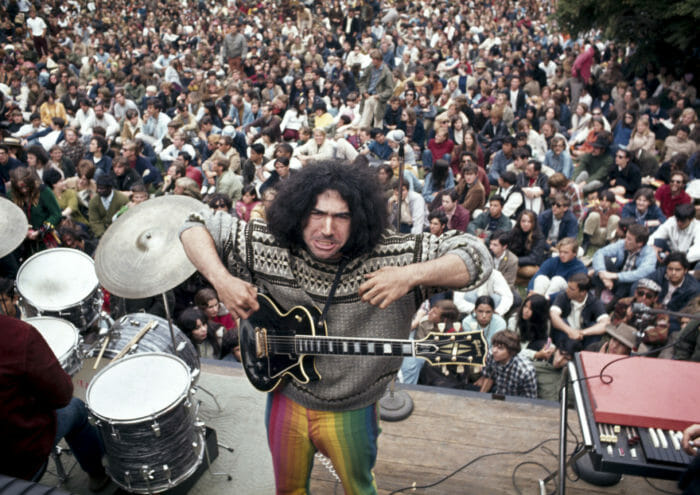

Ron: This was in the Speedway Meadow of Golden Gate Park. We had two flatbed trucks back to back. I sat down on top of the driver’s compartment but I wasn’t there to take pictures, I was there to listen to the music. I would get stoned and I had three Nikons around my thigh—a wide angle, a normal and a small telephoto.

Nothing made Jerry happier than an audience that didn’t have to pay, that was getting off on his music and was sitting right in front of him. So everything was perfect and he expressed his happiness by doing these silly things, like turning to somebody he was really familiar with and making those kind of ape faces.

I remember the pants too. Mountain Girl went shopping one day at a fabric store and bought this heavy canvas that was used to make beach chairs. Then she took apart one of Jerry’s pairs of Levi’s, created a pattern and then used the canvas to make these pants.

Ron: That’s the guitar I bought for Jerry. This was when I lived still over the hill in my fancy house before I moved into 710 [Ashbury St]. I was getting broke, it was a Saturday morning and I had counted up how much money I had, which was 900 bucks. That’s not a lot if it’s all the money you have in the world and you have $5 a week in income—although I think by that time we got it raised to $15.

Anyhow, just like I did every day, I drove over to 710, parked my car and went into the house. That’s when Jerry said, “I found my guitar, help me raise the money to buy it.” Now, this whole association with the Grateful Dead was more like a religious experience than anything else that I could name. Nobody was making any money. It wasn’t about money. It was about commitment and feeling and lifestyle and all that stuff. I had 900 bucks and when Jerry said, “Help me raise the money to buy the guitar,” I asked, “How much is it?” He told me, “900 bucks,” so I said to him, “I have 900 bucks.”

So I drove back to my crib over the hill to get my 900 bucks. Then I came back to the house, put Mountain Girl, Jerry and Sunshine in the back, and I rode in the front like a chauffeur to Dana Morgan’s Music Store in Palo Alto where Jerry used to work. Now usually I don’t buy anything without negotiating but Jerry wouldn’t even let me speak.

There he is on the top of Mount Tamalpais with the guitar. It’s the same place where my picture “Garcia Playing for God” was taken.