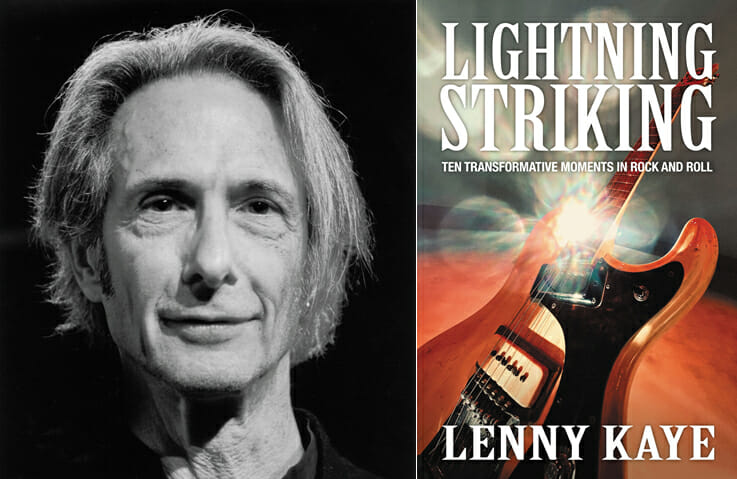

Interview: Lenny Kaye Tracks Ten Transformative Rock Moments

“I had no desire to write your standard-issue memoir,” Lenny Kaye says of his new book, Lightning Striking: Ten Transformative Moments in Rock and Roll. “I’m not too interested in celebrating my time on this earth. I’m interested in celebrating the music’s time and how it grew. I bend the knee to the music.”

Kaye, who recently celebrated his 75th birthday, has been entwined with the rock world ever since he joined his first band in the mid ‘60s. He began collaborating with Patti Smith a few years later and that musical relationship endures to this day. In 1972, he created and curated the pioneering garage-rock compilation Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1965–1968. Kaye has gone on to work with artists such as Suzanne Vega, Jim Carroll, Jessi Colter and Soul Asylum.

Through it all, he has maintained a career as a music writer. In addition to magazine pieces and liner notes—for which he’s received three Grammy nominations—he co-authored Waylon Jennings’ self-titled memoir and later penned the captivating work of cultural history, You Call It Madness: The Sensuous Song of the Croon.

In Lightning Striking, he chronicles rock’s evolution by exploring essential dates and locales. “It was really like going to a given city and becoming a part of what was happening,” Kaye reflects. “I really enjoyed the opportunity to dig very deeply into a musical genre and a conglomeration of creative artists. I didn’t want to be a tourist. I wanted to be a tour guide of these elemental places where rock was transformed.”

Even though You Call It Madness focuses on music from another era, it explores a number of themes that appear in Lightning Striking. To what extent do you see the two books as analogous or interrelated?

Lightning Striking seemed like a nice way to look at the music in the same way that I looked at the crooning era through three very different singers: Russ Columbo, Bing Crosby and Rudy Vallée.

In a certain way, I regard You Call It Madness as my great work of art. It’s certainly not a topic that many people are interested in these days. Bing Crosby is pretty much forgotten as an innovator and, of course, nobody knows who Russ Columbo is.

I wrote the book because I heard about Russ Columbo on late-night radio and I thought, “Man, what a wacky story. Who is this guy?” This was in the early ‘90s and maybe, if the internet back then was what it is today, then the next morning I would have found out more than I needed to know and never gotten into it. But instead, I had to go to the library and pull up microfilm of the Daily Mirror from 1934. All of a sudden, I got pulled into this tale, which was so involving. I was truly obsessed for eight years while investigating this corner of American civilization.

I was drawn to Russ Columbo because of the strange circumstances of his death and the letters they wrote to his mother for 10 years after he died. But, as I began to explore the surrounding social milieu, I came to understand what this music of the ‘20s and ‘30s did for 20th-Century pop music. It kind of moved the music in a weird way into the modern era.

I think we’re currently at that same part of the century where we’re leaving the music of the 20th century behind and there’s a whole new kind of music on the horizon. We’re not even sure what it’ll sound like. I can kind of tell what it will sound like by listening to hit radio. But it really hasn’t formalized into a specific genre, in terms of the way that we classify music. It’s very much based on hip-hop and there’s a lot of pop technology going on. But perhaps by the year 2032—when we are a hundred years away from the world of Bing Crosby and Russ Columbo—there will be something that is entirely new that will make the music that I write about in Lightning Striking as old-fashioned as the crooner era. I’m all for that.

Some of my favorite moments in Lightning Striking are when you focus on labels like Fortune Records that have fallen into obscurity. It reminds me that one can learn as much about culture from Charlton Comics, as from DC or Marvel.

I like ones that are under the radar because that’s where the truest reflection of the culture is. It’s funny you mention that because I have some boxes of comics that I hadn’t looked at in years and, for whatever reason, I’ve kind of gravitated toward them. There are a lot of those Charlton science-fiction comics from the 1970s that are really fascinating. They’re not as high class as Marvel or DC, but they’re definitely more revelatory.

That’s why I like Russ Columbo. He wasn’t Bing Crosby. He probably wasn’t going to transcend his time. Maybe he would’ve if he’d lived, but I’m not sure. So his tale reveals the truth beyond the superstars. That’s what I tried to do with Lightning Striking.

It’s that concept of “scenius,” the Brian Eno word, [which Eno describes as “the intelligence and the intuition of a whole cultural scene. It is the communal form of the concept of genius.”]

Yes, there are some superstars and there are geniuses that make a very big impact. But I’m more interested in the tales of what it was like hanging out in the club. Who were the minor players? Who were the people who would be left behind in a certain way? That tells the tale of their particular moment in time and space.

At CBGB—to take the scene that I’m most familiar with because I grew up with it—there were the artists who would graduate from the club and go around the world. But the ones that capture my heart the most are the groups that were there for a night or were third on the bill. They reveal the heart and soul of what that moment in time meant to the creation of this ecology of ideas. It’s not just the bands onstage, it’s the audience reflecting them. It’s the mood in the club; it’s the kind of off-the-beaten path sense of all these scenes as they have a chance to grow and understand each other. That’s what interests me.

Take the bands that have been elevated by Nuggets. To me, when you discover that strange group from Des Moines, Iowa—who’s not just listening to The Beatles, but also to some other local band—you get a real sense of what it was like at its most elementary level. It’s kind of exciting.

If you look at that bill that I talk about at the beginning of Lightning Striking—the Alan Freed show in 1952—Paul Williams was the headliner. But who was Varetta Dillard? Who was Danny Cobb? These were the ones who were work-a-day R&B artists, and this is what they did—they’d get on the bus and go on to the next show. These are not names that would become famous, but they definitely made everything happen. And in that happening, in the way it evolves and grows within any particular scene, is where the interest lies for me.

It’s why I actually have so many details in the book. As you get deeper into it, you find things that are forgotten. My job as a cultural historian— starting from Nuggets, where many of those bands were not as familiar as the top-shelf ‘60s groups—is to make sure they keep living. So if I put Varetta Dillard’s name in the book, somebody X number of years from now will be reading it and say, “Who is Varetta Dillard? I’d like to listen to ‘Mercy, Mr. Percy,’” and she will live on. It’s like that concept of the Mexican Day of the Dead—as long as these people are remembered, they live on. We try to keep those people who do good work and are a part of our artistic community alive so that they can be discovered. Then, perhaps—like William Blake, who died unknown, or Buddy Bolden—they will find their place in history.

The book is rich in detail and nuance. Did it come together as you initially envisioned it?

To be honest, I didn’t think the book was going to be as deep as it turned out to be. I kind of knew about each moment in time. I figured each chapter would take a couple months to write—it’d be like a long liner note if I were doing a compilation album of these particular scenes. But once I started getting into each one, my own sense of organization and completion and wanting to tell the tale right took over. With all of them, I knew an overview, but I didn’t know those kind of details that would reveal the heart and soul of how it happened. So I let myself go as far in each of the chapters as needed and, in the end, each of them took about six months. I didn’t work on it all the time, but I was thinking about it all the time.

What I wanted to do was to tell the evolutionary history of rock-and-roll through its flash points and how they touched me in a very small way—whether I was an eyewitness, a fan or somebody marveling over how crazy a scene could be, as in the metal chapter.

I wanted to enjoy it the way I enjoy music, which is going to a record fair, rooting around, finding something that intrigues me and following it along. I call it playing in the fields of the Lord—going in there and seeing what rises to the surface in one’s imagination. I’ll be like, “Oh, look at this: Christian-gospel reggae.” Or I’ll get into Hawaiian lap steels. I’m drawn to the classic rabbit hole. Sometimes it’s for a night—I’ll find an artist and investigate who they were and who their contemporaries were. Sometimes it’s longer, like the year where I was deeply into bebop, once I understood it through the persona of the pianist Dodo Marmarosa. He once pushed a piano out a third story window to hear what it sounded like when it hit the ground. He later wound up in a mental hospital in Pittsburgh after being the go-to bebop pianist for Charlie Parker’s Dial sessions, among other things. I spent a good year investigating the music and the surrounding social milieu of West 52nd St.

So after I had the concept and a frame of what I wanted to do with the book, it kind of wrote itself, although I had to do a lot of heavy lifting and research. I needed to figure out how to tell the tale and to tell the tale honestly—to understand what these groups wanted to be, how they became who they wanted to be and what happened after they were able to become who they wanted to be.

Most of the chapters don’t start on the year. They start much earlier because I’m interested in the process—how a scene develops and how it comes to be. Once it kind of crests is when it’s well understood and, to me, that’s when it becomes its own cliché and predictable, even if a lot of great records will still be made.

Take punk, for instance. As it moved over to England and took on the attributes of The Ramones, it became, in a certain sense, less interesting for me than at CBGB where all the bands had a punk sensibility but they all interpreted it differently. There’s that Tom Verlaine quote: “Each band was like an idea.”

I like that lack of specific definition. I’m fascinated by the moment when the galaxies form out of amorphous cosmic clouds and something comes together. Then often, after it’s figured itself out, that’s when it’s time for the next evolutionary growth. I believe all the little scenes that I’m writing about in the book kind of predict the next one. They’re each reactive and they’re going to change the sound. Hair metal will move into grunge, which is evolution.

I like progression. The one thing I never say is, “Music was better then.” I might like the music better then, but it wasn’t better. It was just the music then. And the music now will soon be then. It’s the way of the world. [Laughs.]

In the English chapter, I talk about skiffle and how it was kind of the Americans returning the music that they borrowed from the British Isles. That, to me, is a kind of circular influence that really makes you understand that we are really all together in this. One thing can lead to another and that will lead to another, kind of like a game of telephone. Then when you get to the 12th piece of influence, it sounds completely different. It’s how we all grow as musicians and as artists. I like that. I’m curious where I’m going to next.

When I think about cultural transmission with the U.K., I typically turn to the blues artists that British musicians helped us rediscover.

I did not know Slim Harpo or Muddy Waters until I heard them through The Rolling Stones. Then I went to the sources from there.

Scott Morgan of The Rationals [from Ann Arbor, Mich.] started playing “Money,” not because he heard Barrett Strong in Detroit, but because he heard the song through The Beatles.

I love the way cultures go back and forth, and forth and back. Very few of the American bands who hoped they were The Beatles actually sounded like The Beatles, except for maybe The Knickerbockers. But they all took elements of it and created this homegrown garage music that had a different sensibility to it. In the same way, The Beatles listened to Motown and John Lennon said he wrote a song because he was hoping to emulate Smokey Robinson [“Not the Second Time”]. Well, the song doesn’t sound anything like a Smokey Robinson song.

Of course, we’re talking only English-speaking things. I’ve always hoped that Johnny Hallyday would get into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame because here’s somebody who took an English form of music and made it truly French, paving the way for that French offshoot called yé-yé. That could have been a fun chapter—the yé-yés of Paris. My editor in England also said to me, “I wish you would’ve done something on Lagos.” I don’t know anything about that music, but I’m willing to learn. So maybe when the next obsession comes rolling down the pike at me, I’ll be deep into Afrobeat. But you know, so many records, so little time. [Laughs.]

There’s a great line in the book, where you write, “I have become the poster on my teenage wall.” What does that mean to you?

Well, we are all part of a continuum. I’m sure that there’s a poster of the Patti Smith Group on somebody’s wall and they’re looking at that for inspiration and aspiration. It’s a continual build through evolutionary layers. Cities continually build on what came before.

It’s a great feeling for me to have become that poster because, when I was a wannabe rock musician growing up in New Jersey, the Fillmore was my holy place. Now, I’m at the Fillmore playing on New Year’s Eve, just like the band on that poster. And perhaps the poster from that night is on somebody’s wall. So I’ve become what the poster represented to me, which was my place within the music I love.

In addition to Varetta Dillard, who you mentioned earlier, can you name some other artists whose music you hope will be discovered through the book?

I have to say Mayhem, even though their story is lurid and jaw-dropping. Their albums are pretty darn good if you like the heavier end of metal, as I do. Of course, I also love The Teddy Bears and The Fleetwoods. We do contain multitudes.

I’ve always been attracted to the Norwegian black metal thing just because it was so outrageous. But, if somebody listens to “Freezing Moon,” they’ll hear a really good track from a style of music that probably believed its dark side too much and definitely was as outlandish as metal can be. I also hope—even though they’re somewhat popular worldwide—someone will listen to Babymetal’s “Gimme Chocolate!!”

With Ace Records, I curated a double CD set with a guy named Alec Palao that’s like the soundtrack to Lightning Striking. I was able to put in people like Danny Cobb from the Cleveland chapter. Professor Longhair is also in there. I’m sure there are a lot of people who have never heard Professor Longhair, despite the long shadow that he has over New Orleans music. I would hope, from the Philly chapter, that somebody would listen to how good Frankie Avalon’s records are, like “A Boy Without a Girl.” Of course, there’s also music from the San Francisco chapter. I loved being there in 1967—seeing the bands before they became mega and enjoying Big Brother & The Holding Company, even before Janis hit the stage. They were my kind of group.

When I read about the San Francisco scene from that era, Quicksilver sometimes gets lost, although you offer a corrective in the book.

I hope that I’ve given enough props to Quicksilver because John Cipollina is my favorite guitarist. I mean, the Mount Rushmore is Jimi Hendrix, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and, for me, Rory Gallagher. But John Cipollina—man, what a wild animal.

I love Quicksilver. They’re probably my favorite San Francisco band. I saw them whenever I could. That thing that you mentioned about becoming the poster on my teenage wall, well, when we play the Fillmore, I stand on the side of the stage that John Cipollina stood on so I can really feel his energy.

Later this year will mark the 50th anniversary of Nuggets’ original release. New listeners continue to discover it. How surprised have you been by its legacy?

To be honest, I’m astonished. It’s mind-blowing because, if you go back 50 years from 1972 when I put that record together, you’d be in 1922. Records wouldn’t have even gone electric yet. You’d be thinking about people who wanted to be Al Jolson.

A lot of what I have been doing over the years is tied in to making sure my favorite records keep on living and that these names have a chance to move into a new century. After Nuggets, that would later include Russ Columbo because, when I started investigating him, he was about as unknown as can be.

But in 1972, if I would’ve thought that we would still be talking about Nuggets 50 years later, I would’ve been paralyzed by trying to make it something that it’s not, which is a very listenable album of mid-‘60s bands of which I happened to be in one. These were the bands I was drawn to as I roamed the country and collected records.

It’s not really about garage rock, it’s about great records. That was my brief from Jac Holzman. He wanted to get those songs off albums that had one great song or might have been overlooked. That’s why you have something like “Oh Yeah” by The Shadows of Knight, as opposed to “Gloria,” the national anthem of garage rock.

I didn’t worry too much about the categories. Sagittarius’ “My World Fell Down” has as little to do with garage rock as anything. My parameters were large—I was really just putting together a bunch of songs that I liked, and that seemed to psychically fit together. Some of them were only three or four years old when I started writing the list. So I had no historical perspective.

I caught a mood kind of instinctively and unconsciously that resonated with a lot of people who felt that this music had a lot of heart and soul and yearning in it. I was first out of the block to be honest, and I had my pick of a litter, except I couldn’t get “96 Tears.” But I was given a lot of room to breathe from Elektra.

I just found the box where I have a lot of the correspondence and scribbled names of records and artists that I had thought about. Rhino Records is planning a five-LP box set for the fall Record Store Day, where they’re going to have what would’ve been volume two and then maybe an album of what we call castoffs— things that I considered but which never really fit in with whatever I was doing.

The fact that the album lives on says that it definitely spoke to a moment in time and to something that people desired from it. It was also a revelation of a genre, which people hadn’t quite figured out. I got there early because, a few years later, there would be Back From the Grave and Pebbles and Boulders, when people suddenly realized, “Oh, yeah, this could be a bin in a record store.” So I’m really grateful and happy that I was able to reveal this substrata of rock-and-roll and that it is still being talked about 50 years later because the music still has meaning. It still has a way to illuminate.