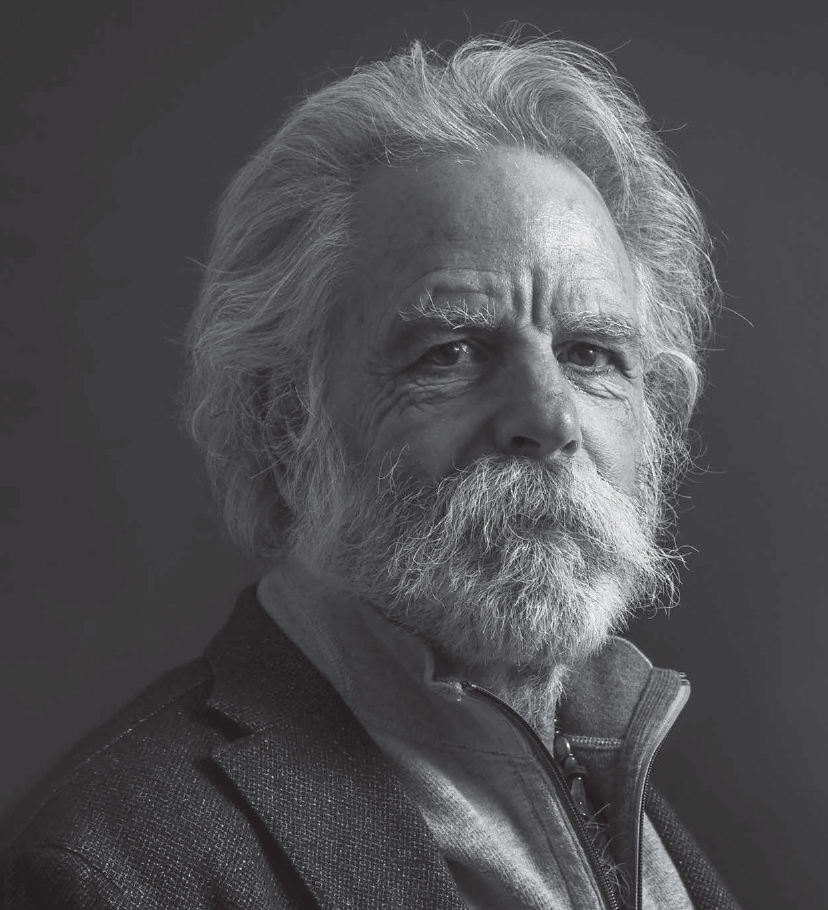

Bob Weir: Saint of Circumstance

photo credit: Todd Michalek

In honor of Bob Weir’s 75 birthday, we revisit his latest cover story…

***

“I would be loath to give my muse short shrift,” Bob Weir declares. “I just couldn’t countenance doing that.”

Weir makes this comment while discussing the possibility of pursuing elected office, perhaps on a local level. He is politically engaged and the idea has occurred to him on occasion. In fact, as he explains, “I once thought about it out loud to my friend Peter Coyote. Then he made me promise that I would never run for office, and he gave me about 20 minutes of good reasons not to.”

However, much of Weir’s reluctance turns on a dearth of available minutes and the possibility that such a time-consuming outside activity could inhibit his creative spark. As he acknowledges, “I still harbor the instinct for doing something like that. The problem is that the logistical hurdles would be enormous. It would be drastically punitive for me because I really enjoy what I do and I’m doing a lot of stuff.”

This remains true despite a global pandemic that has stymied much of the artistic community. While COVID-19 curtailed Weir’s spring tour with Wolf Bros and postponed his summer outing with Dead & Company, he has remained undaunted and prolific. Over the past year, he has delivered solo online performances, offered full-show streams with an expanded Wolf Bros and even debuted a completely new outfit, The Lame Ducks. Meanwhile, he has continued apace with an opera, a memoir and a concerto grosso. He’s also just announced a partnership with Third Man Records, who will release a series of Wolf Bros LPs over the coming year. Oh, yes, and he’s been fighting the good fight against internet latency as well.

Looking back on the past year, one memorable moment was your solo version of the “Star-Spangled Banner” for NASCAR. It’s fascinating how things have changed. When you performed the national anthem at Candlestick Park in April 1993 before the Giants’ first home game, it felt like a subversive prank. The national media was bemused and bewildered by the concept of the Grateful Dead delivering the anthem on opening day.

What was really interesting to me was the way the entire media ecosystem fell in love with that footage. It was the first home game after Barry Bonds had joined the team. We had worked up the anthem while we were on the road and we felt pretty good about it. Then when we went out and nailed it—with all the visual spectacle and “Play ball!”—it was shown everywhere and that certainly changed some perceptions about us.

It’s also part of a story that goes back to March of 1992 when we had been on tour. I’d written an op-ed for The New York Times to register my outrage with what was essentially a timber giveaway bill affecting the national forest lands in Montana. The Democratic and Republican senators from Montana were far too cozy with the timber industry and were defending their actions by citing jobs and all that kind of stuff, regardless of the fact that very few jobs were available. It’s all mechanized to the point where two or three guys can clear-cut a forest in a day quite handily. So I’d been conscripted to see if we could fight this bill that was pushing its way through Congress, skating under the radar. It was going to be an uphill battle to head that one off but we were up for the challenge.

We were in D.C. while on tour and I made the rounds through the Senate with Peter Bahouth. At that time, Peter was running Greenpeace and we were trying to rouse opposition. We didn’t make much headway until we got to Al Gore’s office. Al was incensed and he went to the Senate floor and railed against the bill. We got close to defeating it, but not close enough. It passed and went back to the House for markup.

In the interim, the next stop on the tour was Atlanta and CNN had found out that my op-ed piece in the Times was coming out on the morning of our dayoff. [It ran on March 4, 1992 under the title “Forest for Sale: It’s a Steal.”] So they invited me to come down and talk about the bill because there was still time for people to contact their representatives. I got up real early, way earlier than I cared to, and went to CNN. They sat me down, put a bunch of cameras on me and counted down, “Three, two, one, go!” I was sitting in front of a green screen and behind me they were showing footage of a mechanized timber harvesting operation and how few jobs the senators were actually talking about. They gave me a lot of room to work. Meanwhile, I looked across the way to the control room where I could see a lot of commotion going on—a lot of people holding their sides and laughing. Apparently, while this was airing, both Montana senators or their staff members were on the phone with CNN telling them: “Get that guy off there right now!”

But they didn’t, so the guys who were pushing that bill went to their next line of defense, which was ad hominem attacks on me—“Are you going to listen to this drug-addled hippie, or are you going to listen to us?” I really took some heat because we helped sink the bill, and it wasn’t signed into law.

This continued into the next year because the senators took up the bill again in 1993. So I had to endure their line of attack, and they demonized me for quite some time. But the footage from Candlestick supplied the images that led some people to reassess all that.

While we’re on this subject, mainstream journalists disparaged the Grateful Dead for decades without paying much attention to the music, before finally coming around and acknowledging that your canon is part of the Great American Songbook. Were you frustrated by that or was it all irrelevant to you?

It was more or less irrelevant. What the media generally objected to when they disparaged us was the fact that we weren’t fashionable and we made no attempt to be fashionable. They didn’t understand and couldn’t relate—“These guys just simply aren’t fashionable, what the hell are they doing?” The music industry is fashion incarnate. Somebody comes up with a new sound and everybody copies that. And then somebody comes up with another new one and everybody copies that. So that was the media’s appreciation of music. That’s how deep it went.

But slowly, over the years, particularly since Jerry’s passing—although it started a bit before Jerry checked out—it actually started to get across to folks that there’s a body of work here. There’s some really good stuff in there and some amazing storytelling going on. You just have to have enough patience to settle into it. If you do, then you’re going to find that there’s way more there than you might have originally been told by people who didn’t make the effort to listen.

What you describe as unfashionable, I would call timeless.

Well, we’ll see if it’s timeless. [Laughs.] But I haven’t changed a lick, and a couple months ago Vogue magazine called me a fashion icon. I’m not expecting to stay fashionable for long, but that same guy is now in Vogue and GQ. I’m not sure how long I’m going to occupy that esteem in their eyes but, hell’s bells, it sounds good to me. [Laughs.]

Beyond the anthem, in reflecting on 2020, you’ve spoken about trying to eliminate internet streaming latency issues, so that you can collaborate in real-time with other musicians. Have you been able to solve that?

Pretty much. We’ve just started incorporating video into what we’re calling the Lash-Up. So far, we’ve got three guys playing—me, Don Was and Jay Lane. I don’t know how many instruments we can get in there, but I know there’s room for some more. I’d love to try to get DeadCo up on the system but, for the next couple of years, we’re pretty much locked into a 500- mile radius for this system to work. Beyond that, the latency creeps in to the point where you can’t play together anymore.

So my trio can play, and we’d like to see if we can add Jeff Chimenti on keyboards and Greg Leisz on pedal steel. If we do, then we’re off to the races. At least we can rehearse. What I’d love to do is use this technology to do a couch tour where the guys can play from their own home studios. But the thing is: We have a much superior setup at my studio, TRI, for doing video. So it would take a more severe lockdown situation for us to have to go further with it. But in the meantime, we can rehearse with this system.

As of late, Wolf Bros have performed as an expanded unit with Jeff and Greg joining in. Is the band now a quintet?

I enjoy the trio because there’s all that room. I hate to sound like a control freak but I can really feel the atmosphere there and that avenue of expression is a lot of fun. Then again, I really love the stuff that Jeff plays. And the texture of the pedal steel is something that I’ve always adored, and Greg is really good at that. Basically, I’m still sorting it out. So to answer your question, I really don’t know whether to shit or wind my watch right now.

Beyond pedal steel and keys, your last two appearances have also featured a five-piece string and brass section for a portion of the show. How did that come about?

Over the last few years, I’ve been working on orchestrating a number of Grateful Dead pieces, a couple dozen of them. They’re full orchestrations. They’re dense. I’ve been working with a guy named Giancarlo Aquilanti for a while now. We’re putting together what’s basically a concerto grosso, which is a form where there are soloists. It’s kind of like a symphony, but in this particular case, it’s going to probably take three nights to perform the whole thing.

We’ve orchestrated the songs in a fashion where they can be employed modularly, so that, for instance, if we do a three-night run at one venue and then go to another venue, the songs won’t come in the same order. It’s going to be like all my bands do it—every night will be different. And we’re also working up some techniques to get a symphony orchestra improvising for long periods of time. Now, of course, most of what is played by the orchestra is going to be scored. But there are going to be long sections where we have section leaders who are given options. We need to practice it a little bit first, but the fact is that the performances of the songs will never be the same, either.

As part of that, we’re going to embed improv leaders in the orchestra, who can lead their sections. For instance, we’ve got a guy who’s a great cellist, and in the passages where we want to start looking into improvisation, he can lead the charge for that section. We’ve identified five people so far that we’re confident can do this, so we need to work with them as much as we can to get everybody on the same page when it comes to the improv. The five players that we have are quite good and they’re picking it up real quick. It’s sounding pretty plump and full when we try it with just 10 pieces. Frankly, it’s already sounding pretty enormous and I’m kind of happy with it. Right now, we’re due to debut the concerto in the fall with the National Symphony Orchestra at the Kennedy Center. So that’s why we are having them be part of this right now.

We’re also working on getting the band really quiet. I’ve played with orchestras a few times, and the interaction with the orchestra has been minimal because those guys are busy trying to shut out the horrendous volume of a rock-and-roll band. For instance, a rock-and-roll trap drum kit, acoustically, is twice as loud as an entire symphony orchestra without any amplification. So we have to bring all that way down or the symphony players will just leave, which has happened before. I’ve played with orchestras where some of the members have picked up and left. They have little dB meters and they’re protecting their ears. They have every right to do that. So we need to meet them on their terms and we have to learn to play quietly. That’s what we’re doing, to the point where Jay’s playing electronic drums because they don’t make acoustic rock-and-roll drums quiet enough to play with an orchestra.

Turning to other major projects, what is the status of the opera you’re writing, which began with some Nashville sessions a couple years ago?

I’m at about nine o’clock with the story on the opera. I need to figure out where it finishes up. It’s going to turn some heads when it comes out. I intend to do it in two presentations. One will be the orchestration that I did in the studio in Nashville, with real good players and an electric band. Then I’m going to fully orchestrate it as well. When I get the opera done—that’s going to be a couple more years—I want to debut it at the Ryman or the Grand Ole Opry, with Nashville players. Then, San Francisco has a kick-ass opera company so I also want to do the fully orchestrated one here.

Talking about the Ryman and the Opry leads me to your New Year’s Eve performance with Wolf Bros. You covered Jimmie Rodgers’ “Mule Skinner Blues” with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. Whenever I think of that song, I think of Dolly Parton’s memorable version. You’ve said that you’d like to work with her. Have your paths crossed over the years?

I’ve never come within miles of her. It’ll happen one of these days. That’s going to be a trainwreck made in heaven. [Laughs.]

Your work on the opera calls to mind the Satchel Paige musical that you were writing a while back. Is there any chance that it will yet surface?

Every now and again, I talk to Taj [Mahal] about it. We need a script doctor for that one. The problem with the subject matter is that it’s a story about a guy who plays baseball—it’s his life and times. Satchel was quite an amazing fellow but, if we’re going to finish the musical with the notion that we want to put butts in the seats, we need a script doctor to work in some romantic intrigue or the like.

The music’s all set, though. When we wrote the material, we studied hard and wrote the music to sound like the area he was inhabiting at that time. For instance, we went back and studied the music of the ‘20s because he likely was running into that kind of music. And the thing about it is, if you trace his life and times, you’re also on the Chitlin Circuit because that’s where all the Negro League baseball teams played. Those were also the same places that the blues and jazz idioms were born and grew up. So the music’s all set and there’s plenty of it but, after we get a script doctor, Taj and David [Murray] and I probably will have to dive back in and tweak the lyrics.

Speaking of sports, do you think that your own athletic pursuits have impacted your music?

I’ll tell you what, staying in shape puts me in a position where I still have some gas in the tank at the end of the show when it’s time to deliver the mail. If I didn’t stay in shape, I’d have to completely change the way I approach a night’s performance. When I play music, I go into a sort of whole hallucinogenic realm and my body is part of it. My body is part of the expression because, what we’re really doing on stage when the character comes through, is opera. That’s what it amounts to. When I’m singing or when I’m backing somebody else’s singing, it’s an operatic moment. There’s a story being told there. There’s pathos and a whole lot of atmosphere—that kind of thing. The more able I am physically, the more those characters have to work with when they step through me. So I try to stay fit and able.

By this point in your career, as you’ve returned to certain songs over the course of decades, do you find that, when you inhabit particular characters, they reveal themselves anew, which, in turn, alters your performance?

I’m not sure if I inhabit them, or they inhabit me. It’s a give and take situation, I’m pretty sure. But the cool part is that after a while—when you get cozy with these characters, when you start to get intimate with these characters—they’ll start showing you another side of themselves. I’m not sure that I can bring an example up, but new facets of the characters are constantly arising when I’m on stage. I kind of live for that really, because it can be just a little nuance of the character’s personality or mindset that he will display, and there are all kinds of notes that come with that. There are all kinds of melodic and rhythmic figures that arrive with these new aspects of the characters’ makeup. It’s psychedelic. It’s consciousness-expanding.

I’ve recently come to appreciate that my initial exposure to musical improvisation while growing up was through the vocals of Ella Fitzgerald. There’s been a fair amount of vocal improvisation in your live shows over the years. Did jazz vocalists influence you back in the day?

I think the first jazz I ever listened to was probably Ella Fitzgerald, as well. I ought to listen to more of her these days. I do every now and again, and I always love it, but I probably ought to study her a little bit because she had a way about her. I’m also a big fan of Tony Bennett and guys like that—well, actually, there aren’t any guys like that. [Laughs.]

I don’t think I would identify either of them as direct influences on my playing, though. It took years for me to develop the kind of facility that would allow me to play pretty freely with my hands. Your voice comes straight from the inside of your head. So, while that brings a different series of challenges, I’ve actually found that it took much longer to clear the hurdle of teaching my hands to play the scales than it did to sing the scales.

However, way back when, we always listened to people who improvised with their singing. The Swan Silvertones were a big favorite of ours—along with Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. They both had an enormous influence on the Grateful Dead’s choral vocal development.

You’ve said that the idea for Wolf Bros came to you in a dream. I’m curious how often projects will come to you in that form and whether you typically act on them?

A lot of stuff comes to me in dreams. That’s a huge influence on me. I take a lot of direction from dreams. I process all the stuff that I do in my dreams—my playing, my writing, whatever.

Right now I’m working on a book and I try to get to work before I get out of bed. I pick up my iPad and start writing as soon as I wake up because you’re most connected at that point with where you were when you weren’t awake. It is interesting, people talk a lot about reality and stuff like that, but when you’re dreaming it’s not like you’re not there. It’s not like it’s not reality. It’s just way, way different. And dreams are every bit as real to anyone as what they call reality. It’s just another place.

I take a lot of stock in it because things happen faster in dreams. Consequences or occurrences take no time at all to develop, whereas in the waking state, stuff takes a little while before it arrives. But in a dream, you have a sense that something is headed in one direction or another and oftentimes it just goes right there. So you get to see things develop faster, which gives you a perspective on what color something truly is or what character something really has. In a dream, when something comes up, you get a feeling about it and, by God, that’s what it is.

Dreams teach you about intuition because whatever you might intuit about something in a dream, it generally becomes that right away. One’s first inkling of what one is seeing or countenancing in a dream translates in our waking state to intuition. However, intuition kind of doesn’t exist in dreams because as soon as you intuit something, there it is. So I’ve learned to trust my intuition by observing what happens in my dreams.

February marked the 50th anniversary of Stanley Krippner’s Dream Telepathy Experiment during the Grateful Dead’s six night run at the Capitol Theatre. What are your memories of that event?

[Ed. note: On February 18-21, 23 and 24, 1971, Dr. Krippner, a renowned psychology professor conducted a “pilot study” in which a randomly selected picture was projected onto the stage and the audience was encouraged to send this image to a test subject who was asleep in a Brooklyn laboratory. The subject later described his dreams from that evening and, in four out of the six instances, neutral investigators identified a meaningful correlation, with the results later published in the Journal of the American Society of Psychosomatic Dentistry and Medicine.]

I remember not being totally satisfied because of the lack of a concrete nature of the results. But I guess that sort of goes with the territory.

I’d love to see more experimentation on that level because that’s a pretty lush topic. The interrelation of the collective unconscious and where we go when we dream—that’s a mighty interesting subject. At that point, you’re getting to some pertinent discussions of the nature of existence. Is existence defined by what we call matter, is it exclusively matteroriented, or is there something deeper? This is a place where science has yet to really establish a good foothold and this would be one place to go to do that.

So you believe this is feasible? It is more than feasible.

I imagine it actually happens. John Barlow and I had dreams that we used to share, 40 or 50 years ago. There was a character that showed up in both of our dreams that neither of us knew except through our dreams. It was pretty unmistakable that this was the same guy. They weren’t particularly pleasant dreams, but it was pretty clear that it was the same guy. And I’d be surprised if a fair bit of that kind of stuff isn’t happening pretty much at all times, but we don’t take much notice of it.

Was that during a time when you were living in close proximity or was he off in Wyoming?

We were living in fairly close proximity. I imagine some of that is distance sensitive and some of it is not. If you read the writings of certain yogis, they suggest that some of what we call a telepathic or telekinetic interaction can be subject to the inverse square ratio. I guess it all depends on what frequencies you’re vibrating at. Like I said, I’d be more than game to pick that train of thought back up a little bit to see where we can take it.

You mentioned the memoir that you’re writing. Throughout your career as a songwriter, you’ve taken certain songs out of circulation and brought them into the shop for a tune-up. The printed word is a little less fluid. Have you contemplated the more static nature of this storytelling medium while you’ve been working on the book?

Yes, I have. I have some friends in the city here in San Francisco who run an outfit called Prezi. It’s really well thought out presentation software. I started using it just to sort of outline and storyboard my book, but it became apparent to me that one also could present a book in that format and then leave it open to the addition of video clips, musical clips and audio clips. You could also have related chat rooms, discussions and stuff like that. The book could be constantly evolving, and if something occurred to me that I wanted to insert into the book, then I could also do that.

So I’ve got two notions of what it is I’m working on right now. I’m working on what I call the tome, the thing that you go to a bookstore and buy, bring home and leaf through. Then there’s what I think of as the book itself, which is the story, and I may try to get that out in a multimedia format of some sort. I’m not done thinking through it yet but there’s no reason that I can’t tell the story both in a tome and in a more expanded format.

The tome, the classical presentation, is what I’m focusing on now. The words and how they fall together—the lyricism—is going to be important in telling the story. Whoever the character is—and I’m talking about me now, the guy that I probably don’t understand and probably never will—he’s nonetheless fighting to get out through my fingers. So I’ve got to let him do that first and then look at the multimedia presentation and let him guide me.

To what extent have you been surprised by the shape of the narrative?

It’s all still manifesting itself. The book is a work in progress.

However, I will say that I’ve found that I really enjoy writing a bunch—at least on a good day, with that caveat. There are some mornings when I’ll have a tough time with it and I’ll have to punch my way through. Some days I’m only good for 300 words but other days I’ll get on a roll and write 1,000. It’s all still coming together.

As you look back, I’m curious about two figures, Elvis Presley and Miles Davis. You once shared a memorable bill with Miles at the Fillmore West. Did you ever have direct interactions with either of them?

No, not with either of them. We were on the bill with Miles and we were completely awestruck. I’m not sure that I wanted to meet him. I’m pretty sure he had little interest in meeting us because, from what I could tell, he didn’t particularly dig being famous. He just had to be there because that’s what he did. He had to be famous because you’re going to get famous for doing what he did. But he was there to play music— bring music out of the heavens and into whatever place he was playing. I’m not sure that the scene that surrounded us made all that much sense to him or had all that much sway on him.

Elvis, I just never met. As far as I was concerned, the Elvis that I got to know when I was eight years old had moved on by the time I was 10. He was no longer doing the stuff that I found so attractive.

Dead & Company celebrated a relatively quiet five-year anniversary after your tour was postponed due to the pandemic. In thinking about the group within the context of your career, can you talk about how the band’s sound has evolved?

There’s so much of it that I can’t quite look at it that way. It’s not possible for me to keep track of all the nuances and changes that have occurred over time. I see it as one enormous flowing river of music or one enormous wave of music that’s continually crashing and I’m just surfing it.

I’m just happy that we’re all still going after it. We have plenty of stories yet to tell.

Continuing with the 2020 timeline, at the very end of the year, you performed a set for the Georgia Comes Alive virtual fest as The Lame Ducks with Jay Lane, Jeff Chimenti and Dave Schools. Is that something that might continue?

Well, first off, Dave’s from Georgia. That made us feel a little more authentic speaking to Georgians about voting. Dave’s also a good friend of mine and he’s something of a neighbor. He lives not that far from me and he uses my studio up here a bit. So we often have occasion to play together and something might pop out of that down the road. There’s plenty of time for it to evolve but my plate is full right now.

In looking back on the year as a whole, did quarantine lead you to rethink your relationship to music in any way?

Something really important happened—I’ve recently rediscovered analog music. I finally got a good turntable and realized what I’d been missing for the last few decades since CDs took over and I stashed my record collection. What I’ve finally come to realize is why I can’t listen all the way through a CD—it tires your brain.

There’s plenty of scientific proof at this point that supports this contention. The audio standards for digital music that were derived and codified back in the ‘70s—and are still being used for standard CDs and what you hear over the web—are just too low-resolution for your brain. Your ear might not be able to hear the difference but your brain senses it, and it causes stress in your brain because it has to work to assemble and make sense of what it’s hearing from the digital reportage.

I discovered kind of early on that I couldn’t listen all the way through a CD and I figured it was just because I was getting older. I couldn’t keep my attention. But then I recently put a turntable back in my system, started playing records and found that I could listen endlessly to music.

That took me back to my teen years. When I was teenager, we used to go over to a friend’s house and bring a date. We’d put on a record and snuggle up on the couch. Then we’d put on another record and another record. That’s what kids did back then, but they don’t do that anymore because you can’t listen to that much digital music in its current form. So I want to get involved more fully in getting higherresolution music into people’s ears because, if you listen to digital music in its current state, there’s a certain part of your brain that just wants to turn it off. It’s noise.

Back when I was a kid, people were much closer to the music. In my generation, we held music in our hearts and I’m not sure it’s that way anymore. I want to bring music back to the cultural prominence that it enjoyed when I was younger because the artistic community has something to say.

Do you think some of that is because music is so readily accessible that it’s also become disposable?

Well, I weigh that a lot. What you suggest is part of it but I also feel that one of the main reasons that music is more disposable today than it used to be is that people don’t hold it as close as they used to because they can’t. They’re resistant to it—even if they’re not conscious of the fact—because it’s so much work to listen to it. So people just don’t hang as tight.

I think it’s because of the digital medium that has been imposed on our culture. And if we raise the technical standards of digital music substantially, I think that music will be much more culturally prominent in our society. The technology is here; it’s been here for years. It’s just a matter of getting the whole industry to retool and shift to higher-resolution music. I think that’s important because there are a lot of thoughts and feelings that can’t be expressed in words, so we need artists to help us do that.

Neil Young made a run at this with Pono but he couldn’t quite break through. What have you taken away from his experience?

Neil certainly had the right idea; I’m a campmate with him on this one. He would go on TV to explain himself but I think the company could have offered additional support for his educational campaign. Pono worked, although the problem with it was you couldn’t put it in your pocket because it was triangular. I think it would have done a bunch better if it had been more portable.

That said, there’s ample opportunity to get high-res music on your phone. Especially if you’ve got 5G, the technology exists to get high-res music streamed on your phone these days. I think the folks who make the devices that people carry around should place a focus on that.

I think the entire industry would do itself an enormous favor by making the effort to bring everything up to the best possible standards. People would buy more music and music would become more important to them because they’d love it more. They’d like it more and they’d love it more.

Tidal is doing a good job with streaming hi-res music but there’s work to be done. I’d like to see more people involved. Maybe someone will read this and reach out to me. I’m easy to find.

Do you think some of the issue is the way that music is presented? It’s so balkanized. People are now often exposed to it in very narrow bands through algorithms. It’s not like when you were growing up with those amazing AM stations or even the FM of the ‘70s, which offered a broad palette of genres. Even if the sound is improved, I wonder if part of the problem parallels a larger social issue—we don’t hear one another anymore.

Well, once again, I think it’ll take care of itself. I agree with you on all of that. And that’s basically marketing, which is going to balkanize everything—it’s going to compartmentalize everything because that’s how marketing is done. You identify a demographic and you serve that demographic. If you’re a record company, there are several demographics and you serve each of them what you think they want to hear. But the fact is, as they say, a rising tide floats all boats. If music becomes more culturally important to everybody, then I think the buzz and energy that creates will spill over and people will listen to other idioms that they’re not used to listening to.

If people are more drawn to listening to music than they currently are—and this will happen naturally if music is easier to listen to—then the availability of different styles of music will become more attractive to everyone. I don’t think music will be quite as balkanized as it used to be.

Back when we were younger, we used to listen to all kinds of music at all times. The Grateful Dead—when we were hanging out, just ourselves—listened to everything. We listened to North Indian classical music, the deepest blues, the farthest out jazz, contemporary classical, country music— we grew up on all that stuff. We developed a much deeper appreciation for all the idioms and where they agreed with each other and where they departed from each other. We embraced the similarities and we embraced the differences.

N21: Dean Budnick