“Trips Festival” (from _Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III_)

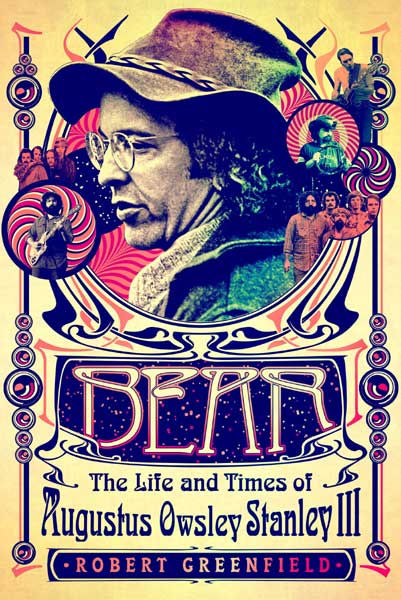

Journalist Robert Greenfield the author of numerous books, including Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock and Out and Dark Star: An Oral Biography of Jerry Garcia, returns to the San Francisco music scene of the 1960s with his latest work, Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III. Born into Kentucky political royalty and the namesake of his paternal grandfather, who was a congressman, senator and governor, Stanley became the chemist who supplied LSD to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters at the Acid Tests. His reputation soon extended across the globe and included accolades from Dr. Albert Hofmann, the first person to synthesize the drug.

Greenfield’s book, which is full of anecdotes and insight, tracks Stanley’s life from his early days in the South through his final years in Australia. The following excerpt explores the onset of his relationship with the Grateful Dead, when he became the group’s patron.

On many levels, the psychedelic ‘60s truly began at the Trips Festival held at Longshoreman’s Hall at 400 North Point Street in San Francisco on the weekend of January 21, 22 and 23, 1966. Stewart Brand, who would go on to create the Whole Earth Catalog, came up with the original concept along with a musician and visual artist named Ramon Sender. With Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters as the featured attraction, by far the wildest of the three events took place on Saturday night.

Kesey, who had just been given a six-month sentence on a work farm as well as six months of probation for his marijuana bust at La Honda, had made front-page news in San Francisco two days earlier by getting arrested yet again along with his companion Carolyn Adams, aka Mountain Girl, for smoking a joint on the roof of Brand’s apartment in North Beach.

No doubt, in part, to show their continuing support for Kesey, somewhere between 3,000–5,000 revelers, who were stoned out of their heads on LSD that Owsley had provided, jammed a hall that was only supposed to hold 1,700 people. In the words of Grateful Dead biographer Dennis McNally: “There were simply more people tripping in a single room… than anyone had ever seen before.”

As Jerry Garcia would later say, “It was total insanity. I mean total, wall-to-wall, gonzo lunacy…. Everybody was just partying furiously. There were people jumping off balconies onto blankets and then bouncing up and down. I mean there was incredible shit going on. Plus, it was like old-home week. I met and saw everybody I had ever known. Every beatnik, every hippie, every coffeehouse hangout person from all over the state was there, all freshly psychedelicized.”

What, with Hells Angels punching out members of other motorcycle clubs in the hallways as one of the Pranksters tried to force Big Brother and the Holding Company off the stage after they had performed just one song, the scene was so crazy that no one could control it. Which did not stop Bill Graham, who had only just begun putting on shows at The Fillmore Auditorium and had been brought on to help run the event, from doing all he could to stop the Pranksters from letting people in for free.

After running all over the hall with a clipboard in his hand in search of Kesey, Graham finally found him standing at the back door letting in a constant stream of bikers. To keep the law from knowing he was there, Kesey was attending the event in a silver space suit with a helmet. After trying, in vain, to get Kesey’s attention, Graham finally lost control and began screaming at him. Without saying a word, Kesey simply flipped the visor of his helmet down and went right on doing as he pleased.

As Bob Weir of the Grateful Dead would later say of Bill Graham that night, “We were with the Pranksters and the buzz was, ‘Who’s that asshole with the clipboard?’” Aside from Jerry Garcia, with whom Graham would forge a lifelong bond on Sunday night by trying to put Garcia’s shattered guitar back together so the Dead could play (which they never did), the only other person at the Trips Festival who understood what Bill Graham was all about was Owsley.

“It was completely out of control and he was trying to control it, and of course he couldn’t, because the harder you tried to grab it, the more slippery it became. I was real stoned when I came into contact with Bill, and I could see right through all the bullshit, and I realized he was half-terrified by what it was and was doing everything he could to control it, and to suppress the realization that there was something special going on there besides something that was obviously making money.”

Owsley brought Tim Scully with him to the Trips Festival. Then 26 years old, Scully had skipped his senior year in high school to begin attending the University of California at Berkeley, where he majored in mathematical physics. Having already built a small computer in middle school and a liner accelerator in high school, Scully had left the university in 1964 to work as an electronic design consultant.

A few hours after having mailed in his tax return on April 15, 1965, Scully had taken LSD for the first time. Possessed by the notion that acid was a better solution to society’s problems than technology, Scully then spent months tracking “down the source of his dose,” who was of course Owsley. After spending weeks carefully checking Scully out, Owsley brought him to the Trips Festival to see how he would react, and the two then began working together on assembling state-of-the-art sound equipment for the Dead as well as the wholesale manufacture of high-quality LSD.

One week after the Trips Festival, on January 29, 1966. Owsley joined the Grateful Dead at the Sound City Acid Test. During the event, held in a radio station in San Francisco, the band tried to record what they had been doing live to accompany the swirling madness created by the Pranksters. During the evening, Bob Weir “first sort of logged into Owsley. He was dressed in medieval garb, had a pageboy haircut and was wearing a ruffled shirt, and he was a dandy. Of course, I was loaded on LSD, so all that had its own little resonance with me.

“I was on Owsley acid when I met Owsley, and he seemed like one of us. I was 18 years old and he was as old as Kesey, at least 30, but they were both more like kids than most kids you were going to see. We connected right away because he was a very, very interesting guy and seemed to know something about everything, and that appealed to me.

“If you got involved in a discussion with Owsley even back then, you kind of had to pack a lunch. I think Phil was his closest contact in the band. They had already bonded because they both had really high IQs and real good retention of information and they were both really curious. Together, they added up to different kaleidoscopes, if you will.”

Then 25 years old, Phil Lesh had attended Berkeley High School and the College of San Mateo before transferring to the University of California in Berkeley, where he dropped out after a single semester. Originally a violin player, he had also studied the trumpet and was an avid devotee of avant-garde classical music and free jazz. While working as an unpaid recording engineer at KPFA, Lesh had met Jerry Garcia, who talked him into becoming the bass player for the band that was then still known as the Warlocks. Unlike Garcia, Lesh had been formally trained and so could read music as well as write charts.

Lesh and Owsley had first connected with each other at The Fillmore Acid Test on January 8, 1966. Having last seen a completely freaked-out Owsley dragging a chair across the floor in Muir Beach, Lesh thought Owsley now looked “like a conquering hero or some Robin Hood figure out of swashbuckling antiquity.” Wearing “an Aussie digger hat and a leather cape,” Owsley seemed, to Lesh, “every inch the figure of the psychedelic warrior… a man who knows he’s on to something cosmic and eternal.”

Walking up to Owsley, Lesh extended his hand and said, “So, you’re Owsley. I feel as if I’ve known you through many lifetimes.” Immediately taking the conversation to another level, Owsley replied, “You have, and you will through many more to come.” Lesh then felt as though he were living in Owsley’s head, which may have been “the result of all the trips I’d taken using his product.”

Never one to pass on an opportunity, Owsley then asked what he could do for the band. “Phil said they did not have a manager. Having no interest in that role at all, I declined the offer. He then said they had no soundman, and I figured I could be good at that since I had audio experience in radio and TV. By the time of the Trips Festival, I was their soundman.”

At the Sound City Acid Test, Owsley and Lesh spent a good deal of time together raving at one another. “Other than Jerry,” Lesh would later write, “I’d not known anyone with as great a breadth of interests before, and it seemed to me that he was actually articulating some of the fuzzy visions we’d had regarding the Meaning of It All.” For Lesh, hanging out with Owsley was “like being in a science fiction novel.”

Right from the start of what became their enduring friendship, Owsley felt much the same way about Lesh. “Phil was the one I met first, and whenever we would get high together, we would hook up telepathically. It’s funny because, in many ways, we were absolutely opposite. He’s a Pisces born in the year of the dragon and I’m a Capricorn born in the year of the dog, but I had grown up with my father, who was also born in the year of the dragon and so I could always tell when I was pushing too hard with Phil in the wrong direction and when to back off.”

Although Owsley did not know anyone who had any experience managing a rock band, he had, by then, already met Rock Scully at a show featuring the Lovin’ Spoonful that Scully had helped put on at Longshoreman’s Hall as part of the Family Dog collective on October 24, 1965. In Scully’s words, “That was when he first hit on me. He said, ‘I’ve been watching you, Scully, and you’re doing a good job. Are you making any money on this show?’ I said, ‘I think we’ll do good, but it all depends.’ He really wanted to talk business, but I was in the middle of a show and trying to keep it all together. Then he said, ‘You’ve got to hear this band.’ They were still the Warlocks then, and although I had already heard about them from Kesey, I forgot about all of this pretty quickly because I had a show to do.”

Then 24 years old, Scully had grown up in Carmel, Calif. His stepfather, Milton Mayer, was a well-known Quaker activist who had once hosted his own network radio show. After graduating from Earlham College in Indiana, Scully had attended San Francisco State, where he became involved in a series of massive civil rights demonstrations. During the summer of 1965, Scully had begun managing the Charlatans, a psychedelic band, who were doing an extended residency at the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City, Nev.

Scully finally saw the Grateful Dead perform for the first time at the Fillmore Acid Test on January 8, 1966. Although he told Owsley that the Dead were “extraordinarily ugly and would probably never make it commercially,” Scully also confessed that he had “never heard a more amazing band musically.”

Owsley knew that “the Dead needed a manager and Rock had been involved in the Family Dog stuff. None of my other friends knew anything about managing or had any experience doing this. So it was a matter of nobody knowing how to do anything and the musicians being exploited by most managers while having no say in what they did. I shared that with Jerry Garcia and the Dead, and they all thought it was good idea for me to talk to Rock about this. So I suggested it to him.”

Having set on his sights on Rock Scully as the person who was best suited to manage the Grateful Dead, Owsley pursued him in what had by now become his usual manner by getting Scully higher than he had ever before been. “Owsley saw me as a businessman who was interested in music. I told him where I lived and said we could talk about me managing the Dead. So he came over to my house in the upper Haight and brought some DMT and said, ‘You gotta smoke this before we talk about anything.’ We did, and instantly it was as complete an enveloping hallucination as you can possibly achieve on anything. Almost like an elevator. A friend of mine was there and he took one puff and fell over.”

Before they smoked DMT together, Owsley had asked Scully to go through his extensive record collection and play some music. “So I put on the first Rolling Stones album and it really helped. It was a shred of reality I could hold on to while I was sitting on this rug and then swimming in it, and everything I saw looked like that. Early on, Kesey had told me, ‘If you’re ever tripping and you go down that hallway and open the wrong door, just remember it was something you took. Don’t get afraid because that will only make it worse. Just remember you took something and it’ll wear off.’ Which helped me save my ass.”

When Scully finally came back down from the DMT about 30 minutes later, “Owsley was expounding on this theory about music and how it reverberated and vibrated with our nervous systems, and then he went on this whole ethno-musicology rap, which made absolute sense to me because I had studied the subject myself. “He was talking about the importance of what I had been doing, and I hadn’t really seen it before in that scope. He said: ‘In the promoter position, you have to try to get the artist for as little as possible so you can make money. What I’m proposing to you now is that you protect the art and protect the musicians by becoming the manager of the Grateful Dead and trying to get as much money as you can for them.’ He imprinted me with this, and I also think he thought he would have influence over me, which he did. He selected me and he selected Garcia as well because he saw that Kesey was getting too wild and was not going to focus on the band.”

Once Scully and his partner, Danny Rifkin, had decided to throw their lot in with the Grateful Dead, Owsley continued to influence the musical direction in which the band was going by convening group sessions in his cottage in Berkeley. Long before the term gear head had ever been invented, Owsley was already obsessive about procuring the best possible equipment for whatever task he was involved in at the moment.

Before ever meeting the Grateful Dead, Owsley had already purchased and installed a sound system in his 35-by-55-foot living room in Berkeley that far surpassed what even the most fanatical hi-fi enthusiast at the time might have dreamed of owning. Looking like “something that someone had rescued from behind the screen at the local movie theater,” his Altec Lansing Voice of the Theatre system consisted of two large wooden cabinets, each of which was “about the size of a small fridge.” Equipped with a 15-inch speaker, a driver that was “about four inches in diameter,” and “a little horn mounted on top,” each cabinet weighed a hundred pounds. Owsley then ran the sound through a McIntosh amplifier with “two channels, 40 watts per channel.”

In Rock Scully’s words, “Owsley brought us together in a whole other way because he had a cottage in Berkeley where there were no neighbors who could complain about the noise and the place was packed full of gear. He had tape decks and really good microphones and great speakers. It was the ideal haven that was just as high-tech in fidelity terms as you could get back then. He also had these tape loops, and so for Phil and Jerry and all of us, it was just a playground where we could get something going on a tape, start a loop, and then improvise on top of that.”

When the Grateful Dead decided to follow the Pranksters to Los Angeles in February 1966 to play a series of Acid Tests down there, Owsley provided the money that enabled them all to make the trip. The band departed so abruptly from San Francisco that Jerry Garcia left his yellow, four-door Corvair parked in a gas station in Palo Alto. All of Bob Weir’s clothes were in the trunk, but neither he nor Garcia ever saw the car again.

After getting on a jet plane for the first time in his life, Phil Lesh flew to Los Angeles alongside Owsley. “It was a red-eye flight,” Lesh would later write, “and we were the only two people in the back of a 707.” Because Owsley was footing the bill, Melissa Cargill, Tim Scully and Rock Scully (who were not related to each other), Danny Rifkin, and a friend of theirs named Ron Rakow also accompanied the band to LA.

Due, in no small part, to the high-quality LSD that Owsley was handing out at no cost to his new circle of musician friends, as well as his continuing willingness to bankroll the band with money he had made from the sale of his product on the streets throughout the Bay Area, the scene around the Grateful Dead had now started to expand at what would soon become an exponential rate.