Something to Talk About: Bonnie Raitt and Grace Potter on Gender Roles, Identity and the Power of Music

The September issue of Relix celebrates the women of rock and roll including our two cover artists, Bonnie Raitt and Grace Potter. A portion of their conversation is presented below.

To read the rest of this story along with features on the inspiring Sharon Jones, budding acts like MisterWives, Shovels & Rope and Amanda Shires as well as much more, pick up the September issue or subscribe here.*****

*****

On a Thursday afternoon in mid-August, just a day before returning to the road to begin late-summer tours that would extend into the fall, Bonnie Raitt and Grace Potter checked in from opposite coasts for a freewheeling 90-minute discourse. Potter, who called from California, is wrapping up a cycle in support of her self-titled record, during which she split from her longtime band the Nocturnals and took to the road with her new Magical Midnight Roadshow. Raitt, who was enduring 100-degree temperatures in Manhattan, had just appeared on Good Morning America and Charlie Rose, while promoting her latest album, Dig in Deep.

These two independent women have defined the terms of their own careers while pursuing their muses with verve and gusto.

Bonnie Raitt and Grace Potter first met when Potter was a wide-eyed 16-year-old, as she relates in this portion of this conversation, which also touches on the purported rivalries of women artists and the process of selecting opening acts.

GRACE POTTER: The first time I heard Bonnie Raitt was at the Sugarbush ski area [in Vermont], playing with Bruce Hornsby. I was there with my parents and some dear friends of mine, and it was an absolutely magical sunset show. Bonnie, you were wearing an amazing neon, blue blazer with the biggest shoulder pads I have ever seen.

BONNIE RAITT: Oh, yeah, it was the early ‘90s.

GP: It was a really incredible moment because I remember being a young woman, and I know this feeling happens to a lot of kids, but I just wanted to get up onstage and start singing. I was like, “I hope she’s going to just hand me a microphone because I’m ready I know all the words—let’s do this.”

BR: That is so great. Had I known, I would’ve brought you up.

GP: I was not prepared to be presented to the public at that point. I was a young kid and I think I was naked—I grew up in a hippie world—so I think it’s good that we waited.

Later, when I was 16, I had a friend John [Rosenthal] who worked with you, and he called me at like 2 p.m. in the afternoon and said, “Bonnie’s playing the Boston Fleet Pavilion. If you get in a car, if you can be here by her show, I have a ticket for you.” So I jumped in a car with my CD in my hand.

I didn’t think I was going to ever meet you, but I thought, “I’ll just throw the CD at her and, hopefully, she’ll see it.” Then the mutual friend brought me backstage, ended up getting me in and I was able to meet you. So as a 16-year-old girl, I was backstage and I remember they were serving lobster, and you said something along the lines of: “They’re serving food to match my hair,” or something hilarious. You were being so funny. You were meeting and greeting a bunch of people, and you had at least 35 more people to meet.

I handed you my CD, and I loved what you said, “I gotta tell you something, Grace. I’m so happy to meet you. Thank you for your CD. You know what’s going to happen with this CD? It’s going to go in a really big pile of CDs that I have and, hopefully, I’ll remember to look into it because you seem sweet and John’s a friend of mine, but I can’t make you any promises.” It was so honest and it was not a feeling of “Welcome to the dark side, girl. Good luck…” It was really a reassuring sense of the size of the universe, and how fortunate I was to be back there, giving you the CD as if that was the only reason you were there to meet someone.

I always took that with me, and now whenever people give me a CD, I actually have to be honest with them and say, “I’m not sure where this CD is going to end up at the end of the night. In fact, I’m going to hand it to this person here and she’s going to hopefully bring it to my bus for me, but I can’t be trusted to hold this.”

It’s really carried me through because, just like I wasn’t able to walk up on stage and take the microphone and start singing at a Bonnie Raitt concert when I was seven, you can’t just hand somebody famous your life story and expect that anybody’s going to do anything for you. You have to just be great. I’ve always thought about that experience and how positive it was and how real it was, even though it was a very brief exchange. It was meaningful and it made me want to work harder.

BR: Oh man, that really moves me a lot, Grace. I don’t think I’ve ever talked to anybody who had a story like that. Whenever anybody hands me a CD, I never get to hear what it’s like from their point of view.

John Rosenthal is an activist for homeless people and handgun control. I’ve known John ever since the No Nukes concert in ‘79. He was arrested at the Stop Diablo Canyon nuclear plant demonstration that Jackson Browne and I played on the beach in the middle of the California coastline years ago. You met me after the show as part of a reception to raise $10,000 for various groups. That was what was going on and that’s where the lobster came from because we don’t get it every night.

I remember hearing about you from John, and later hearing your name from the wildfire that happens because I’m always on the lookout for great, new, under the radar artists who I can be inspired by and I can have open a show or I can do a song with or I can talk about in interviews. Your name was given to me by a few people as a spitfire with “incredible talent as a singer and a great B-3 player, with a killer band.” I was told, “Wait until you hear her—you’re going to be so happy that she’s on the scene.”

And that is exactly what happened. You lived up to everybody’s ravings. It was like when somebody first told me, “Yeah, there’s this group called Little Feat,” or “There’s this guy called Gregg Allman— he’s pretty good.”

I was so relieved and felt so great that somebody loved R&B and soul music, and was so original and was such a great writer. I saw some interviews— once you become a fan of somebody, you try to find out more about them to get what they’re like as a person. Reading those interviews, you were so real and I liked your whole vibe. I just think you comported yourself with so much great class and spunk. You’re also so clearly established as a significant instrumentalist and singer as well as a bandleader and artist. That performance in Vegas, that Divas show [with Heart]— I was just proud because I feel like you’re coming from my part of the subculture. I’ve been happy to see you get the response you’re getting.

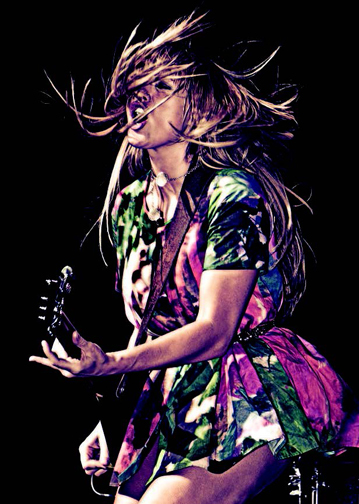

photo by Jay Blakesberg

GP: Wow, that’s pretty frigging great to hear. Some of the women that I have befriended in California since I have been out here working and living, say, “I can tell that you’re one of my tribe,” or “I’m so glad I found my tribe of women.” There’s this real sense of unifying people who can be happy for each other and can build each other up instead of waiting for some ball to drop and something to go wrong so they can move in for the kill.

I was warned, early on, that very few female artists want other females opening for them because, typically, what happens is that people feel that they need to choose: “Do I like the opener or do I like the woman I came to see?”

I do think that’s a real thing. There were eras of my career where I did not have women opening for me. Not necessarily because I didn’t want women, but because I was tired of dealing with the question and dealing with this sort of unfortunate reality that I think people feel they need to choose between one female or the other. It’s like we’re pitting ourselves against each other.

And no, I never felt that from you or a lot of other women, like Emmylou [Harris] and Patty Griffn—people who have become friends of mine in the industry. We are all always happy for one another when we see someone doing well. It doesn’t anger me as much as it used to, but it just confuses me that anyone would ever think they needed to choose.

I do feel that certain people get put on the earth to do a thing, and if you’re lucky enough to find that thing and are able to do it, then you should shine your light as bright as you possibly can. And you’ve been one of those lighthouses. You just are an example of someone who always knew your direction, followed it and set an example.

BR: Thank you. I think it’s important when you put together shows to have it be complementary. You don’t want to have somebody on the bill who’s presenting the same mix of songs. I try to make it so that if one tour is Richard Thompson, then another tour is Mavis [Staples] and another tour is an Appalachian singer named Sarah Siskind, whose voice just slays me. Then I think about my fans, who did they see me with last time, so I try and mix it up every time. Then, selfishly, I just want to hear Marc Cohn every night for a month. I want him to come out and sing “Crazy Love” with me and then, the next time, I want Richard Thompson again so I can sing “Dimming of the Day” with him.

But I’m sure that what you describe is out there. Lilith Fair was a response to everybody telling Sarah [McLachlan] that nobody would come to see more than one woman on the show and she said, “Oh, really?”

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

Potter and Raitt also turned to the social responsibilities of artists and the relationship between music and politics in 2016.

GP: I came at it in a different time than you did, Bonnie. When I was 21 and just starting touring, I was basically told to keep my mouth shut and not talk about it. I remember being pulled aside by somebody who wanted to sign me and he said, “Just keep yourself out of politics. Don’t even bother. We’ve already got one Bono—don’t do it.” Of course, whenever somebody tells me what to do, I do the opposite. [Laughs.]

I didn’t end up signing with him, and I also went ahead and wrote one of my first songs that really captured what I believed to be the political atmosphere at the time. We were in the Bush era, so I wrote a song called “Ah Mary,” which was essentially a euphemism, describing a woman who is actually sort of the state of our country. To this day, I have people come up to me and say that they didn’t realize what the song was about and it then just clicked for them.

But at the time I got into rock-and-roll, there was a lot of fear-based songwriting and/or charged-up energy. I had to break the mold a little bit and step out of that if I wanted to say what I really wanted to say. I had to get creative with it.

BR: For me, I came on the tail end of the ‘60s, which had lots of political music with Bob Dylan, who had a huge crossover hit with “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Before there was Woodstock, there was the Newport Folk Festival and the folk-music revival of the late ‘50s, early ‘60s. All the college kids were grabbing guitars and singing at peace marches and civil rights movement marches with people like Mavis and the Staples Singers.

Those songs catapulted music to the forefront of the counterculture and what was happening against the war and with the civil rights movement. Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth” or any number of other political songs, like “Eve of Destruction,” were front and center in the culture as consciousness changed about music’s role.

I came out of that folk-music revival but that’s also when I fell in love with things like Motown and The Beatles or the Stones. I loved all that stuff. I’ve always loved Fairport Convention as much as I loved John Lee Hooker. You didn’t have to choose, and I still think you don’t have to choose.

By the time I started playing, I identified with a lot of blues-roots music and that form. I didn’t sing a lot of political songs on my records or in my shows but because I was doing a lot of benefits, I would put in political songs and I would be careful not to preach from the stage when it wasn’t a benefit. I knew that would turn people off. I can’t assume that all people have the same political affiliation that I do.

Clearly, I’m progressive. I don’t make any bones about it, but there’s a time and a place for singing overtly political songs. I’ve written a couple that were out-and-out political like “The Comin’ Round Is Going Through,” on my new record. It got to the point where I said, “This is it: I want to write a Stones-kind-of rocker that I can play live and get the anger out about how money has hijacked democracy. And I’m gonna write it in a way that both sides of the spectrum can be pissed o about how this system is broken.” Too many people at the top are controlling what’s going on, on every level. It’s not a democracy if everything’s paid for. You have to buy your way in. It’s an auction instead of an election.

I hand it to people like Don Henley or Sting with “They Dance Alone” or Jackson’s songs or U2 or Bruce Cockburn. There are so many fantastic political writers who are still having resonance as much as The Clash did when punk music was a revolt. But if times aren’t calling for a revolt, you have to come up with music that isn’t pedantic and corny and polarizing. It’s a delicate balance singing political music because most of it isn’t very good. But when you get a great song and you land it and you mean it with all your heart, you can pull off singing it anywhere—benefit or not. I think the artists are the town criers for the culture. We have a responsibility as citizens to be able to speak out about things that are wrong.

GP: Bonnie, I love that new song. It’s not always easy to get it right. It’s easy for us to talk about it in theory, but I can think of too many songs and artists I won’t name whose whole message is just to have a message.

I feel like there’s a difference between saying something and writing a political song. Those are two different things. I’ve seen too many songs where the message gets in the way of the music. Being the town crier is a very important thing, but not if all you want to do is cry—if all you do is complain.

That’s why it’s our responsibility as true artists to find creative ways to make tough news and tough messages and the hard realities of life not just palatable but meaningful. It’s not always easy to get it right but if it’s got resonance and if it’s got a message, then it’s going to feel powerful and timeless, like Neil Young’s “Ohio.”

BR: Oh, man, what a great song.

GP: He wrote it, and then it was out on the radio the next week because he felt that moment was so important because of the timing. But now, here we are, decades later, and it still gives me chills because the energy behind it was important at that moment and it carried on, and made it continue to be important.

For more with Bonnie Raitt and Grace Potter pick up the September issue or subscribe here.