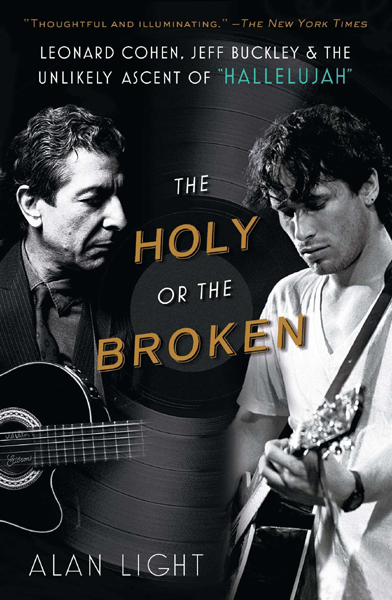

Relix Revisted: The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley & the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah”

In our Jan_Feb 2013 issue we ran this excerpt from Alan Light’s book, The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley & the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah,” which explores the history and legacy of the Leonard Cohen song. As we reflect on Cohen’s passing, we share this excerpt.

Whoever listens carefully to “Hallelujah” will discover that it is a song about sex, about love, about life on earth. The hallelujah is not a homage to a worshipped person, idol, or god, but the hallelujah of the orgasm. It’s an ode to life and love.—Jeff Buckley

“Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld/ So I can sigh eternally,” Kurt Cobain once sang in tribute to the only songwriter, many believe, who belongs in a class with Bob Dylan. But “Hallelujah,” which first appeared on Cohen’s 1984 album Various Positions, has already had one of the most remarkable afterlives in pop music history. The song has become one of the most loved, most performed and most misunderstood compositions of its time. Joyous and despondent, a celebration and a lament, a juxtaposition of dark Old Testament imagery with an irresistibly uplifting chorus, “Hallelujah” is an open-ended meditation on love and faith—and certainly not a song that would easily be pegged as an international anthem.

“Hallelujah,” however, has been performed and recorded by hundreds of artists—from U2 to Justin Timberlake, from Bon Jovi to Celine Dion, from Willie Nelson to numerous contestants on American Idol. It has been sung by opera stars and punk bands. Decades after its creation, it became a Top 10 hit throughout Europe and Scandinavia. In 2008, different versions simultaneously held the No. 1 and No. 2 positions on the U.K. singles chart.

“Hallelujah” served as a balm to a grieving nation when it was used for VH1’s official post-9/11 tribute video; as a statement of national pride at the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Olympic Games in Vancouver; and as the centerpiece of the benefit telethon that followed the earthquake in Haiti.

According to Bono, who has performed “Hallelujah” on his own and with U2, “it might be the most perfect song in the world.”

The earliest manifestation of “Hallelujah,” however, could not have been more humble: When Cohen submitted the Various Positions album to Columbia Records, they refused to put it out. When the record was eventually released, the song was generally ignored. To complicate things even further, Cohen immediately began changing and reworking the song in concert, confusing those few fans who were aware of it.

For a full ten years after its release, it gained extremely limited exposure through a few scattered cover versions. Ultimately, it would be Jeff Buckley’s interpretation on his 1994 album Grace that served as the pivot point for the song’s popularity, but even that recording took a number of years before it truly started to capture the public’s imagination.

Buckley, the son of singer/songwriter Tim Buckley (whom he met only once) first came to New York City from California in 1991, to perform as part of a tribute to his late father at St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn. But it was the following year, when he returned to New York to begin pursuing a musical career in earnest, that saw Buckley begin his relationship with a song that would forever change his own legacy—and, along with it, change pop music history.

Below are two excerpts (with contextual commentary) The Holy or The Broken that deal with Buckley’s relationship to the song.

In the summer of 1991, Jeff Buckley was hired as a roadie and guitar tech for the film-based band The Commitments, who were performing around the United States in support of the movie’s media previews. Glen Hansard—whose band The Frames had formed a year earlier and who would later garner fame for the music of the film and Broadway musical, Once—played the role of guitarist Outspan Foster. Hansard and Buckley became quick friends.

When they got to New York, all that Hansard and Buckley wanted to do was knock around Greenwich Village and retrace Bob Dylan’s footsteps. After returning to his midtown hotel, Hansard got a call from an old friend from Ireland named Shane Doyle, who had opened a café bar in the East Village called Sin-e (which translates from the Gaelic as “that’s it”). He asked the guitarist if he could persuade the Commitments to come down and play; Hansard said he didn’t know where everyone was, but he and his friend Jeff would love to stop by. Doyle penciled them in for a midnight set, and they were thrilled to have an actual gig in the Village.

“I remember singing ‘Sweet Thing’ by Van Morrison,” said Hansard, “and Jeff came up and started singing the second verse. He got really into it and just started going—the cafe was packed, people were stopping and looking in through the windows from the street to see what was happening. He was instantly a star in that moment.”

It was Buckley’s first visit to Sin-e, a place that would assume mythic proportions in his legend. Sin-e had no more than a couple dozen scattered tables, and no real stage, just a small cleared space where a couple of musicians or poets could set up. As the name indicated, the bar, which Doyle and Karl Geary opened in 1989, was initially a haven for New York’s young Irish community; U2 and Gabriel Byrne were known to visit, and Sinead O’Connor, at the height of her fame, could sometimes be found cleaning things up behind the bar.

Hansard recalled that after the set, Buckley “stayed and hung out at Sin-e, washing dishes—he always liked the idea of doing that before he went on, he felt like it grounded him before going onstage.” He told Hansard that he wasn’t going to continue with the Commitments tour—that this time he wanted to stay in New York.

Buckley was twenty-five years old, strikingly handsome, and eager for experience. He threw himself fully and immediately into the city and its music community. He played and wrote with Lucas, but by early 1992, he was stepping out on his own, performing solo shows with an electric guitar at such downtown clubs as the Knitting Factory and Cornelia Street Cafe. Most notably, he was given a regular Monday night slot at Sin-e.

Intimate but low-key, the club was an ideal place for an emerging artist to work. As Buckley began meeting more people, discovering and exploring music from numerous, disparate sources, his Sin-e performances often seemed more like public rehearsals, with the singer trying out material by a lengthy and far-reaching list of artists—Van Morrison, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Bad Brains, Nina Simone, Robert Johnson—and revealing an astonishing vocal range. The two-disc, expanded version of the live EP recorded at the club documents the boundless energy and rapid-fire, free-associating humor that defined his Monday night shows.

“He was trying songs all the time,” said Hal Willner. “Certain Dylan tunes, Edith Piaf—he did ‘They’re Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa’ one night. He just became an amoeba, a jellyfish; he was like a Tex Avery character all of a sudden. He swallowed everything—he was enthusiastic about everything. Mine was one of the record collections that he had access to, and it was great because he was just so hungry at that particular time to listen.”

The two women who ran the arts series at St. Ann’s, artistic director Susan Feldman and program director Janine Nichols, became very close to Buckley. “On the deepest level, Jeff was like a little brother to me,” said Nichols, who preceded Willner in the SNL job and now performs as a jazz singer. “Susan and I took him under our wing, to the extent that he would allow it. At the very beginning, Jeff was the most unboundaried person I ever met—he trusted everyone. It was pure luck that we were trustworthy people, and off he went into the world.”

At one point, Nichols and her family went out of town for a few days, and Buckley stayed at their apartment in Park Slope, Brooklyn, to take care of their cat. While he was there, he pulled the I’m Your Fan record from her shelves, and apparently, for the first time, heard a song called “Hallelujah.” Nichols also lent Buckley the Fender Telecaster guitar that became his signature instrument; on the credits to his Live at Sin-é EP, he thanked “Janine Nichols for her guitar, and Susan Feldman for everything.” Looking back, she said, “I’m kind of knocked out by this influence I had on his musical life, with absolutely no intent to do so.”

Soon, Buckley began adding “Hallelujah” to his repertoire. Steve Berkowitz was an A&R executive at Columbia Records in 1992 when he ran into Hal Willner on the street one night; Willner was on his way to see Buckley at Sin-e, and Berkowitz joined him.

“When I first saw Jeff, he was already doing the song,” he said. “From that very first time I heard his version, it was basically as we know it now, fully formed in the way he would deliver it—this tempo, this pace, and, like most songs he did, it was his immediately, not a copy of anybody’s version.”

Yet Berkowitz added that Buckley was always striving to get even further inside the song, that he wasn’t just satisfied by finding an approach that worked and sticking with it. “I thought of Jeff kind of like a jazz musician. Each performance was unique, according to his feelings that day. He’d play with a different pitch, in a different key. He would play a song with a slide one night, and then maybe never do it again. Feel, performance, emotion is what he was tinkering with. So he kept adding, shaping, reworking ‘Hallelujah.’ ”

“I remember the first time I heard Jeff sing it,” said Bill Flanagan, who at the time was the editor of Musician magazine. “It might have been at Sin-e, or it might have been at the Knitting Factory or someplace—but the first time I heard him sing it, I remember saying to him afterward, ‘Hey, you did the Leonard Cohen song, that was a good call.’ And he said, ‘I haven’t heard Leonard Cohen’s version. I know it by John Cale.’

“I think a lot of people didn’t know the song, and just assumed Jeff had written it. And then it very quickly became the real high point in Jeff’s show; it became his signature pretty early. It was the perfect song for him—because of his voice, but also because of how he looked singing it. It’s a song that begins with King David, and Jeff kind of looked like Michelangelo’s David. And when he sang it, it was as if a Renaissance painting had come to life.”

Ben Schafer, now an executive editor for Da Capo Press, was working as Allen Ginsberg’s assistant in the early 1990s. He went with the poet to a low-scale benefit for a food co-op in the East Village, at which one of the performers was Michael Portnoy, who would later rise to infamy as Bob Dylan’s Grammy stage crasher “Soy Bomb,” and whose routine that night consisted of shooting a carrot out of his ass.

Portnoy was followed by a young singer Schafer did not recognize, “with close-cropped hair and model-like good looks.” He started to stomp and clap, building a beat, and eventually broke into a cover of Nina Simone’s “Be My Husband.” An audience member began to hoot along with him, and Buckley thought that the guy was making fun of him. “In the middle of the song,” said Schafer, “he seethed in the man’s direction, ‘You don’t have to like it, but you don’t have to be a dick about it.’”

Buckley then played two more covers, “Lilac Wine,” another Simone song, and “Hallelujah,” which Schafer recognized from Cale’s I’m Your Fan version. “I was absolutely floored,” he said. “I felt my hair stand up, nearly shaking, breathless, couldn’t believe the vocals and the guitar playing. Bear in mind that I did not even know Buckley’s name at this point—I didn’t know he was Tim Buckley’s son, nothing. It remains perhaps the most single and pure musical experience of my life. I was actually spooked, in a way—it was that otherworldly.”

Ginsberg read a poem and invited Buckley to accompany him. “He was reacting to the lines with little musical hiccups and accents,” said Schafer. “He was listening intently to the words and letting them inform his improvised music. It was extraordinary, and it breaks my heart that this impromptu collaboration wasn’t recorded.”

After the show, Ginsberg and Schafer went to the much-beloved Kiev diner on Second Avenue, and ran into Buckley having dinner with Penny Arcade from Andy Warhol’s Factory, who had been the MC at the benefit. “Allen had a funny, sometimes inappropriate way of asking very direct questions,” said Schafer, “and he immediately lit into Jeff—‘That guy hooting during your first song wasn’t making fun of you. He was enjoying it, doing a call-and-response kind of thing. You seem very edgy. Are you on amphetamines?’”

Schafer felt that Buckley was already feeling the pressure, the sense that all eyes were on him. “Throughout the dinner,” Schafer recalls, “Jeff seemed distracted, nervous, edgy, like a guy with a lot on his mind. I felt like you needed to be careful with him.”

In October 1992, Buckley signed with Columbia records. A year later, he entered Bearsville Studios with producer Andy Wallace along with bassist Mick Grondhal and drummer Matt Johnson to record his debut, Grace. (Former Captain Beefheart guitarist Gary Lucas and rhythm guitarist Michael Tighe would later join for a few tracks.) Wallace, who’d produced albums for Slayer and White Zombie and mixed records for Rage Against the Machine and Nirvana, said that part of the odyssey of making Grace was not only Buckley’s determination to make it a band record, but also how to best capture the energy of his solo performances.

Though the band had been playing shows and rehearsing to get in shape for such ambitious, big-screen Buckley compositions as “Grace” (which would become the title track) and “Mojo Pin,” everyone also agreed that the album should retain some connection to the solo work that first attracted such attention. To allow for maximum spontaneity, Wallace had set up an “acoustic area” separate from the band placement in the studio, which was ready to go whenever Buckley felt the urge to wander over and play by himself.

“After dinner or whenever, Jeff would just come in and run through his set,” said the producer. “We tried to have some semblance of an audience, maybe six or twelve people around, so there was no temptation to stop, but just to play it all through. I wanted to record him as intimately as possible, so it felt like you were sitting two feet in front of him, which was the best place to see him in those tiny clubs.”

“We didn’t do ‘recording sessions,’” said Steve Berkowitz, who was the executive producer overseeing the making of the album that came to be called Grace. “Jeff played the songs, and they got recorded. We tried hard not to have a barrier, just let him play, just be in it. To give him an atmosphere, an immediacy—like Dylan or Miles Davis, just to make music. Andy can make himself invisible, so when Jeff would go over and start to play, he wouldn’t say anything, just, ‘Get the mic into position and let’s go.’

“The process was so developmental, no one knew what the record was going to be,” said Berkowitz. “There was such a deep well of possibilities to choose from, it was such a tough task for Jeff.” As the sessions continued to evolve, it was clear that Buckley needed to keep things going in the studio longer than planned. He left for a while to tour, returning for final sessions in early 1994, now with guitarist Tighe as part of the studio band. A four-song EP, recorded live at Sin-e, was released in December of 1993 as a stopgap to buy some more time.

Buckley continued to accumulate more and more material, but there was never any doubt that “Hallelujah” would be a leading contender for the final album. “There were a lot of these solo songs to sort through,” said Wallace, who didn’t know the song prior to his work with Buckley and had not heard the Cohen recording, “but there was never any question about this one going on the album, that it was something special. It had a magic to it, and that was there from the beginning.”

Buckley returned to the song again and again in the studio; by some accounts, he recorded more than twenty takes of “Hallelujah” over the course of the sessions. Wallace recalls one version that began with an extended minor-key introduction. The final recording is actually a composite created from multiple takes, though memories differ as to how extensive the patchwork actually is: The producer thinks it was “pretty much straight-ahead,” mostly one version with some fixes, while Berkowitz remembers a more elaborate process that stitched together a bunch of parts. “Even when we thought it was done, and we were doing the final mix, Jeff decided he needed to do one more overdub,” he said.

The variations and refinements weren’t dramatic; they represented Buckley searching for the subtleties and nuances he wanted, for a precise shading in the ultimate delivery of this song that he had come to inhabit so fully. A pause here, a breath there, a guitar fill—he was teasing out the slight changes that would express the feelings he was striving to communicate. “He didn’t rearrange the words,” said

Berkowitz. “He simply Buckley-ized them.”

“By the time he recorded it, he’d sung the song a hundred times, maybe three hundred times,” said Flanagan. “He knew what he was going for; he knew what was in it. I think in a lot of ways it was the song he was struggling to write himself, and here he found that someone had written it for him.”

The nearly seven-minute-long recording of “Hallelujah” that appears on Grace opens, unforgettably, with the sound of Buckley exhaling, immediately establishing a romantic sense of drama and intimacy. (Berkowitz noted that the breath came from Buckley’s exhaustion after playing for several hours, not because he was just sitting down and starting cold.) He begins with a gentle, rolling introduction on his guitar that establishes a mood instantly, a riveting sense of focus and intensity; on the BBC, Guy Garvey noted that Buckley’s instrumental introduction “moves from sorrow and uncertainty into confident, joyful chords before he has even sung a word.” Sticking with Cale’s five-verse structure,

Buckley’s guitar accompaniment slowed down Cale’s piano arpeggios and built a subtly propulsive arrangement that was tender yet powerful: A full decade after its initial recording, “Hallelujah” was finally given a melodic framework to match its masterful lyrics.

Buckley’s magnificent, soaring voice radically altered the feel of the song; he himself called the song “a hallelujah to the orgasm…an ode to life and love.” Where the older Cohen and Cale sang the words with a sense of experience and perseverance, of hard lessons won, this rising star delivered the lyrics with swooning emotion, both fragile and indomitable. By balancing this slightly melodramatic reading with the simple, stripped-down sound of a solo guitar, he also avoided having the whole thing become too overwrought and risk collapsing under its own weight.

In Buckley’s hands, “Hallelujah” was transformed into a youthful vision of romantic agony and sexual triumph. (Buckley actually expressed some doubts about the emotional liberties taken by his rendition, saying that he hoped Cohen wouldn’t hear it.) In her book examining Grace as part of the 33 1/3 series, in which each volume is dedicated to the consideration of a single rock album, Princeton professor Daphne Brooks called Buckley’s performance “gospel music with sex, desire and love tangled together and representing the keys to existential revelation and resurrection.”

“When you hear the Jeff Buckley version,” said ukulele virtuoso Jake Shimabukuro, “it’s so intimate it’s almost like you’re invading his personal space, or you’re listening to something that you weren’t supposed to hear.”

“It’s a hymn to being alive,” Buckley said in 1994. “It’s a hymn to love lost. To love. Even the pain of existence, which ties you to being human, should receive an amen—or a hallelujah.”

Glen Hansard—a lifelong Cohen fan, who remembers going to a Cohen concert when he was a teenager in Dublin—compares the two interpretations by way of a 1978 prose piece by Cohen titled “How to Speak Poetry.” Closely paraphrasing the original text, Hansard said that Cohen’s instruction was to “deliver the line and step aside. Don’t lift your shoulders when you say the word butterfly—you are a vessel that’s about delivering the words.”

“So Leonard’s version is typical of what he would do, but Jeff gave it wings, he lifted his chest. He gave us the version we hoped Leonard would emote, and he wasn’t afraid to sing it with absolute reverence. Jeff sang it back to Leonard as a love song to what he achieved, and in doing so, Jeff made it his own. Leonard penned it, but Jeff owned it.”