Mona Lisas, Holy Grails and White Lightning: Brian Chambers and Zoltron on the Expansive Gallery Exhibition “60 Years of the Grateful Dead”

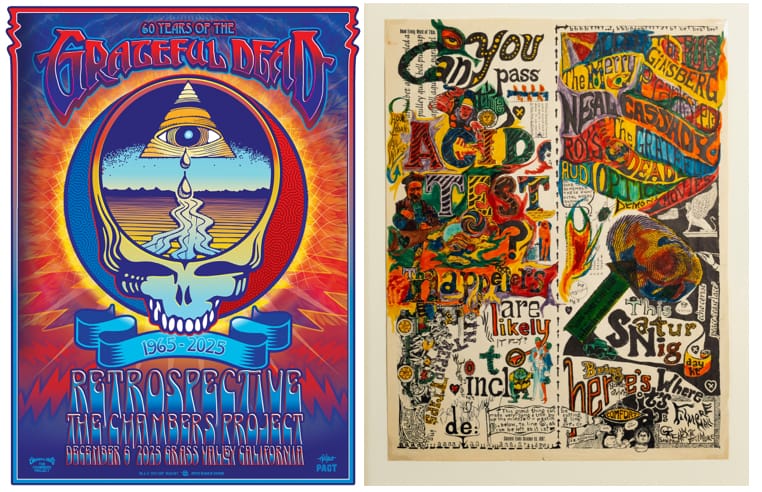

“This is by far the biggest show I’ve ever put together. I’ve never worked on a show this hard and this long. I’d say 90% of this stuff has never been seen,” explains curator Brian Chambers as he describes the realization of an idea that he first envisioned nearly two years ago. On December 6, the Chambers Project Gallery and PACT: Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust will present 60 Years of the Grateful Dead, which is billed as “the most comprehensive exhibition of original Grateful Dead artwork ever assembled.” It will run through June 1, 2026 at Chambers’ gallery in Grass Valley, Calif.

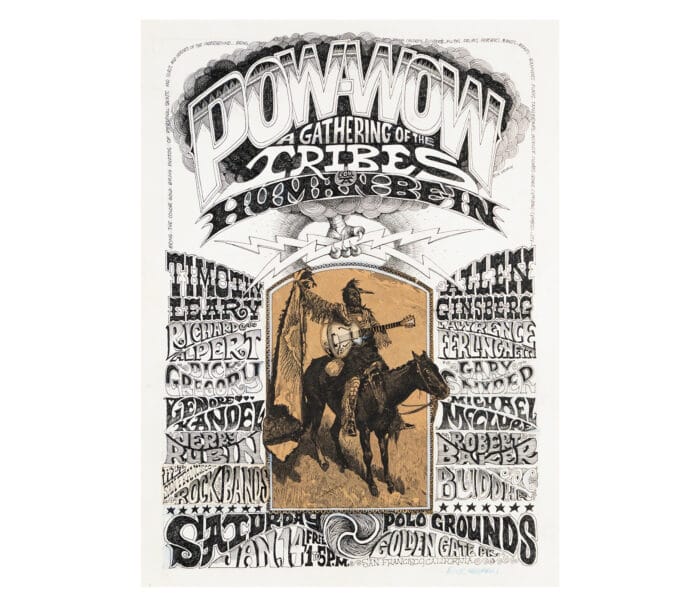

The official opening will be preceded by a special concert event. Grahame Lesh, George Michalski, Peter Harris, Pete Sears, Barry Sless, John Molo and Elliott Peck will come together on December 5 as White Lightning. This one-off collective will perform the music of the Grateful Dead at Nevada City’s Bodhi Hive. The moniker White Lightning offers a nod to Owsley’s name for his batch of acid inspired by Rick Griffin’s poster for the Human Be-In.

Chambers’ passion for psychedelic art began in 1996 when he was still in his teens. Over the intervening years he has built both his collection and his reputation as a pre-eminent curator and gallery owner who manifests a deep appreciation not only for the art but for the artists who create it.

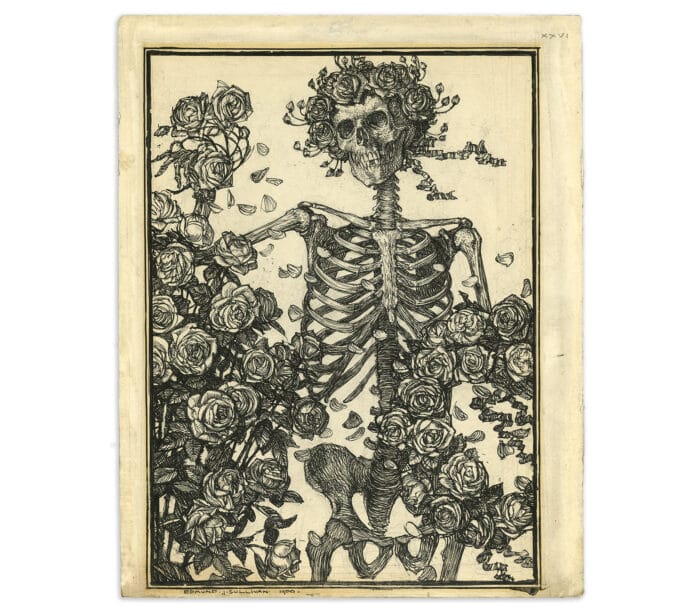

This approach certainly facilitated his ability to assemble the range and scope of posters, paintings, drawings and artifacts that appear in 60 Years of the Grateful Dead. Highlights include Bill Walker’s painting from the cover of the Grateful Dead album Anthem of the Sun, numerous Rick Griffin pieces (such as his pen and ink Hawaiian Aoxomoxoa illustration, his Without A Net cover painting and the aforementioned Human Be-In drawing), original Acid Test posters and a multitude of additional items created by renowned artists, including San Francisco’s Big Five (Alton Kelley, Victor Moscoco, Stanley Mouse, Wes Wilson and Griffin). Also of note is Edmund J. Sullivan’s 1900 drawing A Skeleton Amid Roses, which was later adapted by Mouse and Kelley for the Avalon Ballroom and then Skull and Roses.

As befits such an event, prominent Bay Area artist Zoltron has created limited edition merchandise. Zoltron is the retired longtime Primus creative director who continues to produce posters for the band and various other artists. His work has been collected by the Victoria and Albert Museum, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, The Los Angeles Contemporary Museum of Art and the U.S. Prints Division of the Library of Congress. He also founded the silkscreen print shop Sticker Robot.

Zoltron recalls, “Brian came to me six months ago and said, ‘Hey, dude, do you want to handle some merchandise for the show?’ Now six months later, we’re putting on an event of the ages. With the amount of details in the work, it’s been brutal, but exciting.

“Brian is fearless and he makes things happen at a high level. Some of these pieces are coming from private collections, so they’re all going to be seen together for the first time. To the two of us, and our generation and culture, these are the Mona Lisas. These are the Holy Grails of Holy Grails. So if people have a chance to get up to the gallery, it’ll be like a trip to Disneyland for Deadheads.”

Brian, what’s the first poster you acquired that set you off on your current journey?

B: It’s still hanging on the wall in my kitchen—an Albert Hofmann signed Bicycle Day poster for the 50th anniversary of LSD. It was an event that happened in ’93. I got that two years later in ’95 when I was a sophomore in high school for a thousand bucks. That was a terrifying amount of money for a 16 year old but that was when I realized, “Okay, I’m an art collector.”

Z: It’s funny you asked that because I asked him the exact same thing a little while ago when we were having a conversation. He showed me that image and I was like, “This is a story unto itself—a 16-year-old who goes in fearlessly and spends a thousand bucks on a piece he had to have.” Then just fast forward to the present and there you go.

After the first piece set you in motion, I imagine things really kicked into gear with the second. Can you recall what that one was for you?

B: I can remember a couple of the first concert posters I ended up getting. The Ames Bros did a Pearl Jam poster for a Knoxville, Tennessee show in ’95, and EMEK did a Phish poster for Cleveland in ’95.

I read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas that year, and that was also the same year that Hunter Thompson and Ralph Steadman signed the Dr. Gonzo print edition. So that was one of the first fine art prints I got.

That also was the year I discovered Rick Griffin. That was the year that I discovered the Grateful Dead, the Big Five…

Z: Acid.

B: Yeah, exactly. So I think discovering the psychedelic side of life had a huge impact on what I was interested in. I really started collecting between ’95 and 2002. It was kind of my mission to own everything that Albert Hofmann ever signed. The same with Rick Griffin’s grails. I had mint signed first printings of all his most iconic posters, and I was very heavy into concert posters and psychedelic fine art stuff and ephemera until about 2005. That’s when I started collecting originals.

Is there a piece out there you’ve set your sights on that almost feels mythical to you in its elusiveness?

B: Absolutely. The original pen drawing of the Aoxomoxoa album cover. I’ve been looking for that for 30 years. I have yet to find it, and when I do find it, I’ll move heaven and earth to acquire it.

Z: He has the Aoxomoxoa Hawaii drawing, but not the album cover.

Do you have any inkling where it might be?

B: I’ve got it pinned down to a group of people but I’m not sure who exactly is holding it. I’ve got a pretty good idea of how they came into possession of it and that covers a whole other pile of worms about the provenance. There can be a lot of complexities in acquiring things that have gone through multiple hands where there may be some questionable dealings.

Z: That has a checkered history. It’s like lore or legend at this point. I can’t tell you how many people have come up and said, “Hey, I know where it is.” That’ll lead you into a pursuit that goes into a rabbit hole of sleuthing that could take months, then you come up empty handed and have to start fresh. Over the years a lot of people have they said know where it is. [Laughs.]

Brian, what was the first Zoltron piece you owned?

B: Oh, good question. Probably Primus in Oakland around 2010.

Z: I’ve been working with Primus since the 90s. We started a design company—me Les Claypool, Adam Gates and Larry [LaLonde] the guitar player. It’s funny because during that same era when Brian was in high school we were doing a lot of posters for New Year’s shows, and I’ve been basically doing them ever since. I’ve worked with the band on all their album covers and websites and graphic design. I basically did their art direction for 20 years and still work with them.

What was your entry point to designing art that connects with music?

Z: I was a kid in the 70s in West Marin, which is kind of like a Dead epicenter in Marin County. My older brothers were about 10 years older than me, and in their room they had shag carpet, incense and that kind of vibe.

They called me Doobie and they would blow smoke in my face and feed me pot brownies when I was six. Side note, that probably had something to do with something. [Laughs.]

But on the walls of their bedroom, they had Rick Griffin, Zap Comix and that kind of stuff. They loved Yes with the Roger Dean art—they had belt buckles and denim jackets.

I would trip out in there on that stuff and Goat’s Head Soup [the 1973 Rolling Stones album], which was fucking terrifying. Do you remember Goat’s Head Soup? It’s just a pot of vegetables and a freaking goat head.

I used to take their albums then toss the records and hang the album art on my wall. There was also King Crimson and some other iconic classics that were in my mind for years to come.

Years later in high school, seeing bands live, I was super into the visual aspect of it. I’d see a Butthole Surfers concert where there were visuals and imagery in the background, and I was drawn to that.

When I saw Tool in ’95 or ’96 they were hidden, kind of behind the camera. They would do interviews with their faces blurred-out.

I was super into The Residents and all that kind of stuff. The iconography of the Grateful Dead also was so fascinating because it was almost separate from the music somehow.

So seeing all that stuff and then being in high school and watching these shows and being driven to that artwork made a big impact. Finally, back to Tool, after seeing them on stage and being super high on a handful of drugs, I went home and decided I was going to start making music art.

That’s when I first really pursued it and sent a Residents poster to Arlene Owseichik, who was the art director for the Fillmore. I found her in the Yellow Pages blind called her and submitted art via FedEx. That was my first published piece in ’96, and it’s just kind of gone on from there.

I loved the connection between music and art. My parents were both fine artists, so I got to see behind the curtain on that, and I was never really interested as with this kind of art that I do. I’m still totally driven by it.

Brian, did this show begin with a particular piece or overarching idea?

B: Basically in January of ’24, it kind of dawned on me that December 4th this year, is the 60 year anniversary to the day from which they first played under the name the Grateful Dead.

I also realized that in the past 30 years, I’ve come across a lot of people in my network that had a lot of the most iconic original art from album covers to concert posters, and I recognized it was probably within my grasp to pull it all together and do a retrospective.

So I had the idea last January and I immediately started working on it. I think probably the anchoring piece that really made me realize, “OK, now you’re cooking with gas” was after planning the show and getting the concept dialed, I started going back through all the album covers and saw Anthem of the Sun. Then I went through my Rolodex and called everybody I know to see if any of them knew Bill Walker. That’s the only album cover that he ever did and he never did any concert posters.

Nobody knew him, and it took some time to find his very obscure website. Then after I found it, I shot him an email. I introduced myself and was like, “Hey, man, I’d love this album cover. I don’t know if this painting still exists. If it does, I’d love the opportunity to buy it, sell it, or at least show it. So hit me up and let me know.” Then a couple months later, he emailed me and was like, “Oh yeah, that thing’s been sitting in a box in my sister’s garage for the last 30 years in Sacramento.” That’s an hour away from me, so I was like, “OK, I’ll be there in an hour.”

Right around that same time I also got the Without A Net painting. So after getting together the original painting for what I consider to be the best painted studio album and the best painted live album in around June or July of last year, I realized, “OK, I’ve got a good start here. Now it’s time to step on the gas and really see what I can pull together.”

So I think it’s fair to say it kind of started with the Anthem of the Sun.

Z: And did it end with Edmund Sullivan?

B: I would say so. It was seven or eight months ago that I was able to broker a deal for the original A Skeleton Amid Roses that Edmund Sullivan did in 1900.

Did you know where that was? Was it out there in the world being exhibited?

B: No, it wasn’t out there being exhibited, but it was out there in my mentor’s house. I had known that he had it for 25 years. I knew that it had never been shown in a Grateful Dead context, and I knew that if I could somehow figure out a way to show it, the rest of everything would fall together pretty cohesively and somewhat effortlessly.

So I made that a serious prime target, and after I was able to secure that by the brokering of the deal and the learning of the piece, a lot of other fruit has fallen from the trees and allowed me to pull together a massive body of work that’s going to be mind-blowing to see altogether,

That, to me, may be the most exciting find. I didn’t realize that it still existed as a physical object.

B: I’d say most people don’t. That’ll be the showstopper for sure.

There’s something really compelling about that. It’s not a poster, it’s where all the posters came from. It’s not the album cover that sold 50 million copies. It’s the guy in the studio who made that piece with duct tape and whatever else it took. You see it all there. It’s incredible.

People are going to look at it and understand the process of how it was created and what followed from there all the way to the present.

Back to Bill Walker and the painting in his sister’s garage. Did he recognize it as an important piece or was that not a concern of his?

Z: I can say from my perspective that a lot of artists are about making art and couldn’t care less about the historical value or whatever else. I mean obviously it’s very important to him as a sentimental piece and something he worked on for decades. But as an artist, you make and you move on to the next piece and then you move on to the next piece. Everybody else sort of adds that context to it.

Also, that piece is a lot different than the album cover—that was almost like an incomplete piece. He continued to work on it for another 10 or 12 years. But yeah, there’s something about that. You just keep on going and stick it in the garage, and who knows?

Although, Brian, I’m surprised people didn’t chase it prior to you.

B: That’s kind of ultimately how it ended up in my hands. There was a shady art dealer who had possession of it. He held it for ransom for 15 years and kind of attempted to steal it from Bill. So through that whole experience, Bill was pretty jaded. I think it took a lot out of him just to get it back. So by the time he got it back, he was like, “All right, fuck this. I’m just going to stick this thing away.”

But also for him, he’s been an artist his whole life. He’s not driven by money. He’s Wild Bill Walker. So he just kind of stuck it away, and I’m very proud to say meeting him was a breath of fresh air for both of us, I think.

Z: You guys are both coming from that genuine space. Brian really shined a light on Bill and his art subsequently. So he acquired the piece, but then he did panels and shows to really made it into a thing where Bill was respected and seen at the level he deserved.

Brian’s always coming from that space. That’s why he’s got such good relationships with Steadman and Griffin and all these major estates because he takes care of people. That’s because he cares, which is rarer than you might think in the art world.

B: Unfortunately, I do think there are quite a bit of shadeballs that operate in the industry. So I do take my reputation very seriously and operate from a place of love and respect.

Z: That’s why I show with Brian. I’m drawn to that because he cares and he treats it at the level of respect it deserves. In this day and age a lot of us artists have figured out we don’t really need galleries because we have our own collectors, our own online presence. It’s a lot different than my parents’ era where they would paint and then a photographer would take slides, it would go to the gallery, and they would do everything from framing to showing to marketing to hyping to selling. It’s different now, but Brian’s still got a good balance between the two of those.

I think there’s real value in reminding or informing people about who created the art and the context in which that occurred.

B: Yeah, I mean that’s what this show is all about. Visually speaking, the art in the show is mind-blowing. There are so many iconic works, but what’s more fascinating to me is there are so many stories behind all the works that never get told. So I’m just thrilled to have the opportunity to tell those stories to the world.

Beyond the art you’re displaying, you’ve also created art of your own in conjunction with the show. Can you talk about your approach to that?

Z: We put a lot into not only the show, but into the merchandise as well, which we licensed through the Grateful Dead and built a really excellent, high quality limited package. We went to them, they liked what we were doing and they were cool with it all.

Every single thing is done at the highest level of quality. For instance, we built a 3D cast aluminum, multi-chamber herb grinder, which was an undertaking unto itself. You’ve got to see this thing in person. It’s like a historical artifact that we dug up from the earth after it had been buried for hundreds of years.

Every single thing we put together was like that. Organic cotton shirts, super high-end garments, hand numbered sticker hang tags, silkscreen printed, woven labels, multiple discharge printing, 11-color shirts. For the posters we’re working with AJ Masthay who literally hand carved 11 screens on a linocut and hand printed these pieces. Every single thing is done at that level with the merchandise, but also the show with respect to the artists and the history. It’s very thoughtful and it took a long time to put this thing together.

Brian and I were talking this morning, and we were like, “With the amount of work, this might as well be a huge music festival.” We’ve got a circus tent where we’re going to have the merchant side and we’ve hired a team to help us do it. It’s not unlike a rock concert but it’s an art show. So we’re kind of treating this thing at the highest possible level through and through.

I imagine you want to harken back to something that feels good to people while also advancing the ball in certain respects.

Z: I do think that’s important, and we really did pay close attention to that with the stuff we’re building, not only for this show, but for all shows. I mean, look at silkscreen printing as a medium, which takes a month. It takes time to create the art, to print the art, to air dry each color as you go to the next one.

It’s that same philosophy about going back to this handmade level of craftsmanship, and it’s important. I think in this day and age, everything’s about drone deliveries and instant Amazon where something’s as cheap as it can be to make as much money as you can. That’s not the right approach. So part of it is not about legacy, but creating something that people will adore.

That’s my background with Zoltron and for a lot of us as artists it’s not about maximizing your sales. That has very little to do with it. You care about this thing, and the more experience you get, the more you care and the more you figure out exactly the right path to make that excellent item.

Working with these guys I probably spent a month on this package before I even presented it to the Dead. Instead of being piecemeal, we built something really cohesive and presented it to them. Then a couple days later, a hundred percent of them were approved. So I think it’ll be appreciated through and through—whoever’s going to be feeling the texture of the shirt, even if they don’t entirely understand, they’re going to be get that tactile kind of feel.

The sticker packs that we did are serial numbered. They’re hand printed, front and back.

Even down to the clothing hang tags, we put so much work into the thing. It’s a sticker faced hang tag, which is a logo that we created of Rick Griffin’s Crying Eye with a Steal Your Face—hole punch, kiss cut, back print, 10 point card stock, and then hand numbered on the back. So when you get the shirt, there’s something a lot more to it than just a cheap knockoff white shirt with a Steal Your Face. It’s limited to a hundred pieces, it has some history to it, and it’s important to think that way in the first place.

How did the White Lightning band come together?

B: Well, a good friend of mine named George Michalski is an incredibly talented piano player, who has played with a lot of people over the years. [Michalski spent time with Jerry Garcia and the Grateful Dead at 710 Ashbury, and later performed with the Allman Brothers Band, Blue Cheer, John Lee Hooker, Barbra Streisand, among many others.] He did the soundtrack for Nash Bridges. He’s also a passionate collector, and when I started putting this whole thing together and talking about the musical component, he offered to be the musical director.

At that point, I was like, “OK, let’s put together the baddest Grateful Dead super band that’s within our networks.” So it was a collaboration with the two of us reaching through our Rolodexes and trying to put together our favorite players to share the stage. These particular musicians have never played together as a group. They’re very excited and I feel confident that they’re going to jive very well.

The name White Lightning came about because Rick Griffin’s first major poster was for the Human Be-In, the Pow-Wow, the Gathering of the Tribes. The story on that is Owsley saw the white lightning bolts that are being held at the top of the poster, which is why he named the batch of acid White Lightning for that particular event. So it kind of felt appropriate given that the Dead came from the Acid Tests and Oswley had a heavy hand in all that.

Speaking of the Acid Tests, can you talk about those posters and their provenance?

B: Definitely one of the highlights of the show would be Owsley’s personal copy that he signed. To my knowledge, it is the only Owsley-signed Acid Test poster that he also hand colored and wrote the venue information in the bottom right corner. It’ll be right beside A Skeleton Amid Roses on that wall. I’ve got three Acid Test posters on the wall, one of which Jerry wrote the venue info on.

Those things have become exceptionally rare these days. They’re very hard to find. To my knowledge, they were originally printed in white, yellow, and blue, so there were a few different color variants, but I think less than 30 of them probably exist anymore. We’ve got three of them all with different venue info on them.

Z: What color are yours?

B: I’ve got two of the goldenrods and Owsley’s is hand colored, but it’s white. All three of the Acid Test posters that I have came from one source, and it has been his mission since the 70s to secure the very best Acid Test stuff on the planet. So that’s been his specific area of focus for over 50 years. Amongst the collector community, everyone agrees that this particular fellow has the best Acid Test stuff on the planet.

Brian, can you point to something else that people might otherwise overlook?

B: There’s a lot that I could talk about. For my journey in the arts, this particular show certainly is the pinnacle of my career. It means more to me personally and culturally than anything I’ve ever done.

This is also the formal announcing and launch of my nonprofit called PACT. It’s the Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust, which is really an exercise in a philanthropic way of curation. I’m trying to show what is possible when you’re less financially driven and more culturally examining an artist or group of artists that means the world to you.

The Chambers Project has never really been a traditional art gallery space but this is kind of a shifting of the gears and a different way of thinking and exploring the curating of shows. It’s how I intend on doing it in the future. This is a big one, but I think what is to be learned from this and where we’re going to go after this, is going to get really fun and exciting.

We’re doing a Zoltron show with him next Halloween. We were just talking about how we’re going to take everything we’ve learned from this show and apply it towards that—not just create an art show or a retrospective, but an experience. We want to make it almost that cultural concert level kind of art show vibe.

Z: Part of the Grateful Dead’s interest in this was PACT. They did their diligence and once they realized that it was coming from this genuine place, they were on board because they’re solicited a lot.

Does PACT have a general educational mission? What are your goals?

B: We’ve got a very strong board and a solid two years of programming ahead of us. I know everything that I’m doing for the next couple years, and it’s all quality over quantity. A lot of thought and intention and really doing a deep dive into the history and the culture around everything that is to come.

I suppose our boilerplate mission statement is we are here to celebrate the past, honor the present, and help shape the future of psychedelic arts and culture.

We’re looking into multimedia. I’m working on a Rick Griffin documentary, a Rick Griffin retrospective, a book, a Zoltron retrospective, and just being very thoughtful and intentional with the shows that we’re going to be curating and launching in years to come. We’ll also be trying to do it from a multimedia, multifaceted attack.

Z: Roger Dean is on the board, the Yes artist, and Michael Pearnce, who’s an art critic and professor and journalist at the Lutheran University. There’s a lot of weight to this board, some historians, some artists and so on. It’s going to be something. We’ve got a lot of belief in it.

Thinking ahead to the show is there a specific moment that you most eagerly anticipate?

B: I want people to be like, “Wow, that’s amazing.” I want them to go tell the stories they just heard. Share the lore. Talk about the legacy. Just be excited. Be inspired.