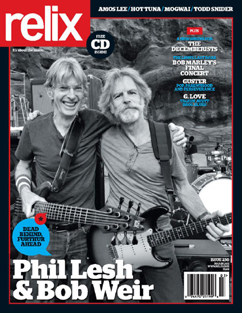

Phil at 80: Dead Behind, Furthur Ahead

In honor of Phil Lesh’s 80th birthday on Sunday, we present this piece from our March 2011 issue.

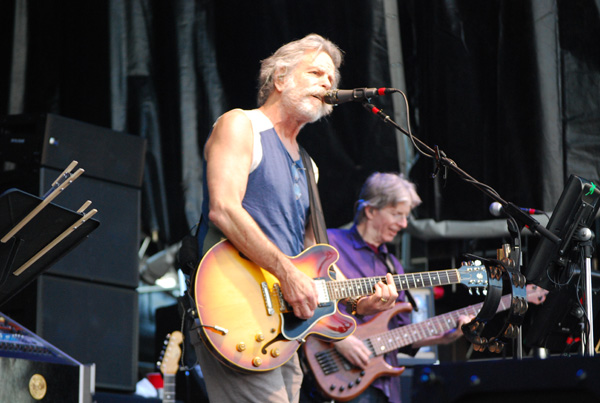

Amid the midnight spectacle that embellished Furthur’s recent New Year’s Eve concert at the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium in San Francisco, a quieter milestone unfolded as well. This occasion marked the second consecutive year that Bob Weir and Phil Lesh had welcomed Father Time and his multihued parade crew with the same full-time band.

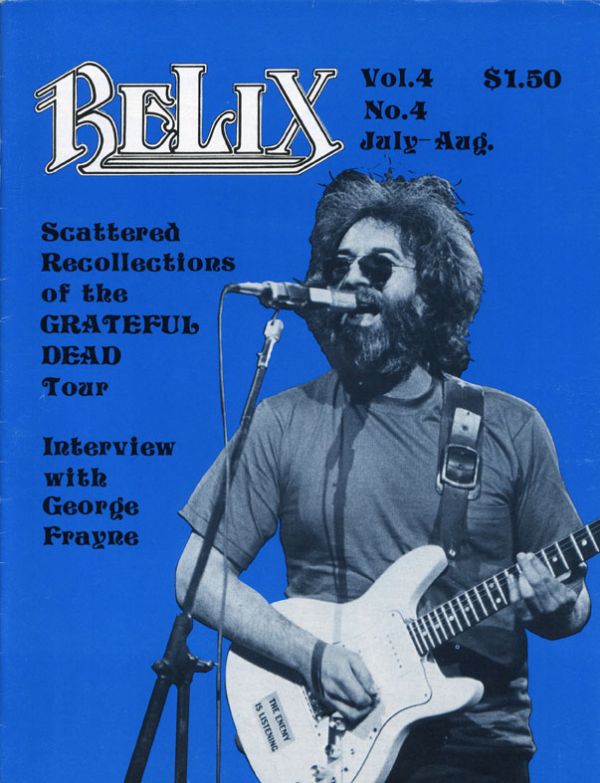

The pair’s preceding comparable back-to-back celebrations took place in 1990 and 1991 during Grateful Dead galas at the Oakland Coliseum Arena. After legendary promoter Bill Graham passed away in the fall of 1991, the group performed one final New Year’s blowout in his honor but then cleared the date from its tour itinerary. Jerry Garcia died in August 1995 and for some time afterward, Lesh and Weir converged only intermittently.

The summer of 1998 saw the pair return to the stage in The Other Ones, a group formed with Grateful Dead alum Mickey Hart (but not fellow Rhythm Devil Bill Kreutzmann), as well as Bruce Hornsby on keys, two guitarists (Mark Karan and Steve Kimock) and a sax player (Dave Ellis, who transposed many of Garcia’s signature guitar lines). However, by August of 2000, when The Other Ones next toured, Lesh was not a part of the line-up (though Kreutzmann had entered the fold), opting instead to focus on his new Phil & Friends project. Two years later, at the Terrapin Station family reunion event in Wisconsin, the core four reconvened as The Others Ones with Jimmy Herring on guitar duty (eventually renaming the group The Dead in 2003). Warren Haynes joined the group beginning with 2004’s “Wave that Flag” summer tour.

During the next five years, Weir ramped up his group RatDog, while Lesh continued to rotate players into a fluid Phil & Friends roster. However, spurred by a collective call to raise funds for presidential candidate Barack Obama, The Dead’s benefit performance gave way to an Inaugural event, followed by a series of spring dates, with Haynes as the lone guitarist. (By then Herring was a fulltime member of Widespread Panic.)

It was during this final stretch that Weir and Lesh reconnected, recommitted and ultimately decided to take things Furthur.

It all began with an e-mail from the bass player to his longtime bandmates.

“After the tour I e-mailed him and said, ‘Hey, that was really fun, I really enjoyed playing with you,’ Lesh explains. “That’s what I had brought away from it and it turned out he felt the same way. From there, we started talking and it seemed like we should continue to play together. We’d find some musicians and take it in our direction, in the direction we wanted to take it.”

That direction oriented them away from Hart and Kreutzmann who eventually would re-activate The Rhythm Devils touring collective that they had debuted in 2006.

“Once you add Mickey and Billy to the mix – and this is more real than one might imagine – you add a layer of expectation,” Weir explains. “A lot of folks in the audience are looking for a walk down memory lane and they’re disappointed if they don’t get that. That’s cumbersome. So Phil and I decided to start fresh with the material and with an outfit that didn’t carry those expectations.”

The pair set out on a divergent musical path that necessitated a shift in personnel. The central irony of this decision, given their objective to divine new bearings, is that a small but vocal subset of the Deadhead community – an admittedly picky lot – would censure their heroes for navigating all too familiar terrain.

It’s a criticism that Lesh dismisses with a shrug as he explains how far it diverges from his intent. “One of the reasons that Bob and I wanted to go ahead with this band was to bring fresh approaches to the tunes, like he was doing with RatDog and I did with Phil & Friends,” he says assuredly. “We treat it as repertoire. In Grateful Dead terms, that means every performance can be different. All versions of the songs are true, just like a fairy tale.”

So Lesh and Weir then required some like-minded storytellers.

“So we carefully assembled a crew of guys,” Weir recalls, “who were familiar enough with the material but came from disparate enough backgrounds. That way, when we pull everybody together, the center is amorphous enough that it gives us the opportunity to take any approach to old material or new material that we might want to adopt at a moment’s whimsy.”

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

The first two musicians that the duo enlisted were RatDog’s keyboardist Jeff Chimenti and drummer Jay Lane. Chimenti had been a familiar face in Weir-Lesh collaborations ever since Terrapin Station while Lane had made some guest appearances with The Other Ones or The Dead. Furthur’s architects envisioned moving him away from the kit and into the role of percussionist, coloring the palette differently than with their previous groups.

Lesh also approached longtime Phil & Friends drummer John Molo only to discover that Molo already had had made a long-term commitment to Moonalice. “So I started listening back to other people I’d played with and listening on Archive.org to different bands,” Lesh recalls. “I remembered Joe Russo from the Jammys. [Lesh hosted the Jammy Awards in 2005 where he appeared with The Benevento-Russo Duo along with Les Claypool and Mike Gordon for “Dee’s Diner” ]. “And from gigs we’d played together in separate bands. [In the summer of 2006, Benevento and Russo joined Gordon and Trey Anastasio for a series of dates on a co-bill with Phil & Friends]. So I listened back to his playing and I told Bob we should try this guy out; we should have him come out and play with us.”

Of all the musicians who would join the new band, Russo had the least familiarity with the Dead catalog but he certainly had the chops, which ultimately added to his appeal.

“It’s fun because he’s so game and brings so many drum styles and approaches,” Lesh commends. “A lot of the time it was really cool to have him play the song his way and it just gave a totally different flavor to it.” “He’s a phenomenal drummer,” Weir echoes. “What he’s doing now is learning the ropes of playing in a larger ensemble and he’s getting a pretty good grip on it. His big oeuvre when he came to us at that point had been a duo and the other guy in that duo [Marco Benevento] pretty much played quarter notes, if that. [Russo] was everything else, so he was awfully busy. He’s simmering down these days and that’s good for the music. There was a lot of material for him to get up to speed on and Jay Lane was real helpful in that regard – he was basically a set of training wheels.”

Yet before the band could hope to hit maximum velocity, it required an additional piston.

John Kadlecik began his training on the classical violin at age nine and didn’t listen to rock radio until six years later. He swiftly made up for lost time as he recalls, ravenously consuming what “they didn’t call classic rock yet, they called oldies: The Who, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd,” he says. “I endured the ridicule of my violin playing peers for listening to the old stuff.”

He soon gravitated toward the guitar. “From ‘84 to ‘87, I blasted through everything I could get my hands on, including some of the hard rock which was the technique-oriented stuff for guitar players,” he says. He received a scholarship to Illinois’ William Rainey Harper College and began studying music before dropping out to pursue the life of a working musician in the Chicago club and bar scene.

During the summer of 1988, at age 19, at the suggestion of a friend, he attended his first Grateful Dead show – or nearly so – arriving at Alpine Valley Music Theatre on the band’s day off during a run when performing four shows in five nights at the East Troy, Wis. amphitheater. “There were a lot of people camping in the parking lot,” Kadlecik says. “So I went in and wandered around. It was the first time I saw a live sitar, so I thought, ‘That’s a good sign.’”

He finally saw the group the next spring, caught the bug, and in 1997, while still appearing with a variety of bands in multiple contexts, co-founded Dark Star Orchestra, which began as a collection of Dead-loving players from various groups who came together for a weekly slot at Martyrs’ in Chicago. The band’s modus operandi was to select a Grateful Dead setlist and then attempt to perform it in the style of the Dead from the original era, with Kadlecik assuming the role of Jerry Garcia.

“I had this idea the first time I saw DeadBase,” the guitarist says in reference to the compendium of Grateful Dead setlists. “I thought this would be a neat way to create a curriculum of study for a really ambitious Deadhead band to do a Grateful Dead tribute and not make sacrifices for the yuppies that only want to hear the Top 40 hits. We would look at each song and listen to three or four versions of that song from the same year and try to interpolate them. It was never a note for note thing – it was about trying to learn where the edges of stretching could go within that aesthetic of taste.

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

“There’s a misperception that DSO played jams note for note,” he continues. “The best transcribers in the world of guitar music would still take months to [transcribe] one show. Part of my drive in doing the setlist thing was an excuse to do ‘drums and space’ every night – to do that kind of unstructured improvisation and have it be different every time.”

Within a year, Dark Star Orchestra had morphed from a weekly exercise in a Chicago club for musicians on their night off from other gigs into a nationally-touring, full-time venture. In 2006, Weir himself sat in with DSO for the first of a couple appearances with the band. (Of Weir’s guitar style, Kadlecik offers, “My favorite metaphor is that he did for Jerry what John McLaughlin did for Miles Davis – as an aggressive, intelligent, innovative support and foil.” )

After Lesh listened to some Dark Star Orchestra shows, Weir’s manager Matt Busch e-mailed Kadlecik to inquire about his upcoming plans. That e-mail sat in Kadlecik’s spam folder for a little while, until the guitarist was cleaning it out one day. He soon found himself flying west with his gear for an audition that took place on a mid-summer day in 2009, with the other future DSO members who would join the nascent group.

Weir acknowledges that some of Kadlecik’s vocal intonations and guitar tones “were to me at least, a little uncomfortably reminiscent of Jerry.” However, he was soon won over.

“We had done some looking around and a lot of listening,” he confides. “We were going to audition a bunch of guys but John came in and we got to playing with him and Phil and I decided, ‘Why bother shopping around, this guy’s great.’ His approach is open-ended. He studied the scales that Jerry studied and he has the ability to play with a fluid tonic. If you’re in the key of A, the tonic is A. The way the Grateful Dead played, the tonic could change in a jam and that’s kind of unusual. Most jambands, if they’re going to jam, they pick a key and stick with it. “If a musician is really good at listening and can hear a shift in the harmonic content of what’s going on and push it in another direction, the jam can find its way into another key – it can modulate. Not all that many musicians are gifted with that ability. We’re not looking to recreate the old days by any means but John’s ability to go with the music trumped what I considered to be the downside – that he tended to sound like Jerry.”

During the course of 1700 Dark Star Orchestra shows, Kadlecik had come to refine his methodology and mode of improvisation. “The one thing I struggled with early on, as a jamming improviser with different bands, is how do you keep all the jams sounding different? How do you avoid recycling the same licks?” the guitarist says. “I’m a believer in the idea that the instrumental melodic components that come with a song have a DNA relationship with that song. Sometimes it’s important to throw that out for spontaneity’s sake or just to rattle cages as it were but there’s still a fractal formula for each song that informs the jam. Even if you throw it out, it’s deliberately not the DNA of that song. So it’s still kind of anti-informing the jam but still giving it its own unique relationship to that song in that moment in the evening.”

It was this approach, in part, that ultimately endeared him to Weir and Lesh. But rather than viewing him as a vehicle to recreate the role of Jerry Garcia, the two realized that his deep knowledge of Garcia’s playing gave him the tools and the vision to help carry the Grateful Dead’s music in an original direction.

“The first song we played together was ‘Playing in the Band,’” Kadlecik remembers. “So, right away, we jumped into it to see where we could take things. It was consciousness altering, leave it at that. I had no idea what Bob and Phil had in mind though. I thought it might be a benefit show. I had no idea they were planning a new band together. After the second day of audition/rehearsal, [Weir and Lesh] pulled the Four Js [Jeff Chimenti, Jay Lane, Joe Russo and John Kadlecik] into a room and told us, ‘We think we have a band, do you want to do it? Can you clear your schedule for 2010?’”

All they needed was a name.

“We were calling it PB and Js for a while,” Lesh laughs. “Then one day we were sitting on my patio and Bob and Natasha [Weir] were over, along with my kids and some other folks. It’s almost uncanny. I said something like, ‘Oh, we need a name,’ and Bob says, ‘We have a name – Furthur.’ Boom that was it. It was just like Jerry and ‘How about the Grateful Dead?’ It was uncanny. It was too perfect. I had to say, ‘ This is a moment.’” “The good ship Furthur is sort of large in our iconic history,” Weir adds. The name, as many likely recall, comes from the International Harvester school bus that carried Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters around the country, as chronicled by Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

By the time that Furthur took the stage for the first time at Oakland, Calif.‘s Fox Theatre on September 18, 2009, the music was already advancing toward a zone that befits the band’s moniker. Furthur debuted with an declaratory jam, which then segued into “The Other One,” “The Wheel” and then “Jack Straw” – a sequence that demonstrated the new group’s facility for dense improvisation balanced by an affinity to lock into a more playful groove.

“On any given night, we make a ferocious amount of music,” Weir explains. “We have lot of firepower in this band and everybody listens as hard as they play. My biggest criticism is that from time to time people can get too busy – a little too notey – although that’s to be expected from a band of guys with the kind of facility that we have. But I don’t think that’s going to get you to heaven. The songs are going to get you to heaven, not the playing.”

To this end, the Fox Theatre run also offered something that the preceding Dead tour had not: a new Phil Lesh composition, “Welcome to the Dance.”

“I think it says something that right away in our first three shows, we were already playing original material,” Kadlecik observes. “At this point, we have almost an album’s worth of material we are playing in the first year of the band’s history and it doesn’t show any sign of letting up.”

Lesh affirms, “I’m trying to bring in new originals as fast as I can and Bob is also. I don’t work very fast unfortunately but we’re both committed to it. I’m also searching out some cool covers.”

One recent songwriting collaborator is someone Lesh has known for quite some time – his younger son Brian (currently a Princeton undergrad and fronting his own group, Blue Light River). “Brian’s lyrics have always struck me as being unusually mature and thoughtful,” says the elder Lesh. “There was this one tune I was having trouble finalizing, so I made a little demo recording of it and asked if maybe he could think up some lyrics for it and maybe change the sequence of events around it a little bit. So he took that on and it came out beautifully [ “The Mountain Song” which can be heard on this issue’s CD sampler]. He also wrote some lyrics for an arrangement of an Ola Belle Reed tune called ‘High on a Mountain.’”

The bassist also speaks with reverence of a performance this past summer at one of Levon Helm’s Midnight Rambles, where Brian and his elder son Grahame, a recent Stanford grad with his own group, Maiden Lane, joined him. “It was the most awesome feeling,” says the proud father. “I think the most moving part of it was singing together because siblings have familial voices that blend really neatly. It was always in the back of my mind that maybe it could happen but now that it is happening, it’s better than I could imagine. It almost seemed like that could be the future.”

As for the future of Phil & Friends, Lesh acknowledges that Furthur’s development hasn’t precluded it but “I’m having such a fun time touring with Furthur and playing with those guys that I haven’t given it a lot of thought. There are some intriguing options that are starting to present themselves but I’m always one for allowing things to happen in an organic, natural way rather than trying to push them in any direction. So I’m just waiting to see what’s going to come up.”

Photo by Jay Blakesberg

Meanwhile, Weir explains that when it comes to RatDog, “that certainly hasn’t run its course but I only have so much time and energy. I’ve got a lot of other projects on my plate right now, too.” These include a May performance with California’s Marin Symphony Orchestra and a solo acoustic gig at the Sundance Film Festival, which may inspire a tour. In addition, he is close to completing a studio that he has been building for the purpose of Internet broadcast.

“One of the shows I want to do [in the studio] is RatDog,” Weir confirms. “I want to get all or at least most of the guys who are still alive who played with RatDog and do a retrospective. In doing so, we’ll probably make a DVD and a record. I’ve got unfinished business with that outfit.”

Weir also mentions that he can imagine another band coming back together. “I actually expect that The Dead will reconvene at some point, but that’ll be a walk down memory lane,” he says. “It will be for those folks who want that, but we can’t live there.”

For now, Furhur is pulling Weir into deeper realms. The personnel has shifted slightly since the band’s premiere, with Jay Lane departing in the spring of 2010 to join his friend Les Claypool in a reconstituted Primus. “We had a feeling it was going to boil down to one drummer,” Weir asserts. “The two drummer business is kind of cumbersome. Even a drummer and percussionist is a bit cumbersome, so it all happened sort of serendipitously.” In addition, backup singers Sunshine Becker and Jeff Pehrson have come on board to sweeten the vocal harmonies and help carry the music somewhere new. In the process, Furthur is playing to a swelling, enthusiastic fan base of longtime Weir and Lesh fans along with many fresh faces who have never shared in the Grateful Dead live experience.

As for fans’ waning yet not altogether abated criticism of Kadlecik, Weir responds: “I think you’ll find over the past year and some, John’s playing and delivery has drifted a bit from sounding that much like Jerry. That’s what we expected; that’s what we’re getting and we’re happy with it. At the same time, we’re making good music and it satisfies us. It keeps us hopping because John is on his toes. When a new opportunity arrives harmonically, rhythmically – whatever – he’s there. He can hear us and we can hear him and he just fits. But if you want it to sound completely new, be patient, it will – soon.”

Lesh agrees: “I think John has gained an enormous amount of confidence and most important to me, he doesn’t have any trouble being himself anymore. “He’s evolved to the point where he doesn’t feel like he has to channel Jerry. He can just relax and play, so that the context of the moment determines how much of Jerry he channels.”

What is undeniable is that Kadlecik and his bandmates have invigorated Weir and Lesh – infusing them with a spirit that has yielded new creative output, while drawing them back to the stage on a consistent basis, as evidenced by the consecutive New Year’s Eve shows. It’s even led the bassist to revisit his recent performances, listening back to live recordings, “mostly to see how I can improve but also sometimes while we’re playing, I’ll notice that there’s some little arrangement that we didn’t quite get right and if I listen back I’ll know to bring it up in rehearsal,” Lesh says.

From Kadlecik’s perspective: “Musically, they both seem on fire with their passion. Every day, I see the same energy as a five year old on Christmas morning with a new toy.”

Lesh, who will turn 71 in March, reflects, “Music is infinite. There’s no end to it and you can never stop growing with it because it won’t let you. Every musical organism – and that’s what bands are – has a life and a mind of its own. Musical organisms grow over time because it takes time to learn each other’s little idiosyncrasies and that’s a human thing. Nothing is perfect out of the box and music is never perfect. Striving toward that goal is an evolving process. It just gets better and better and that’s what I love about it.”

This article originally appeared in the pages of Relix. For more features, interviews, album reviews and more subscribe below.