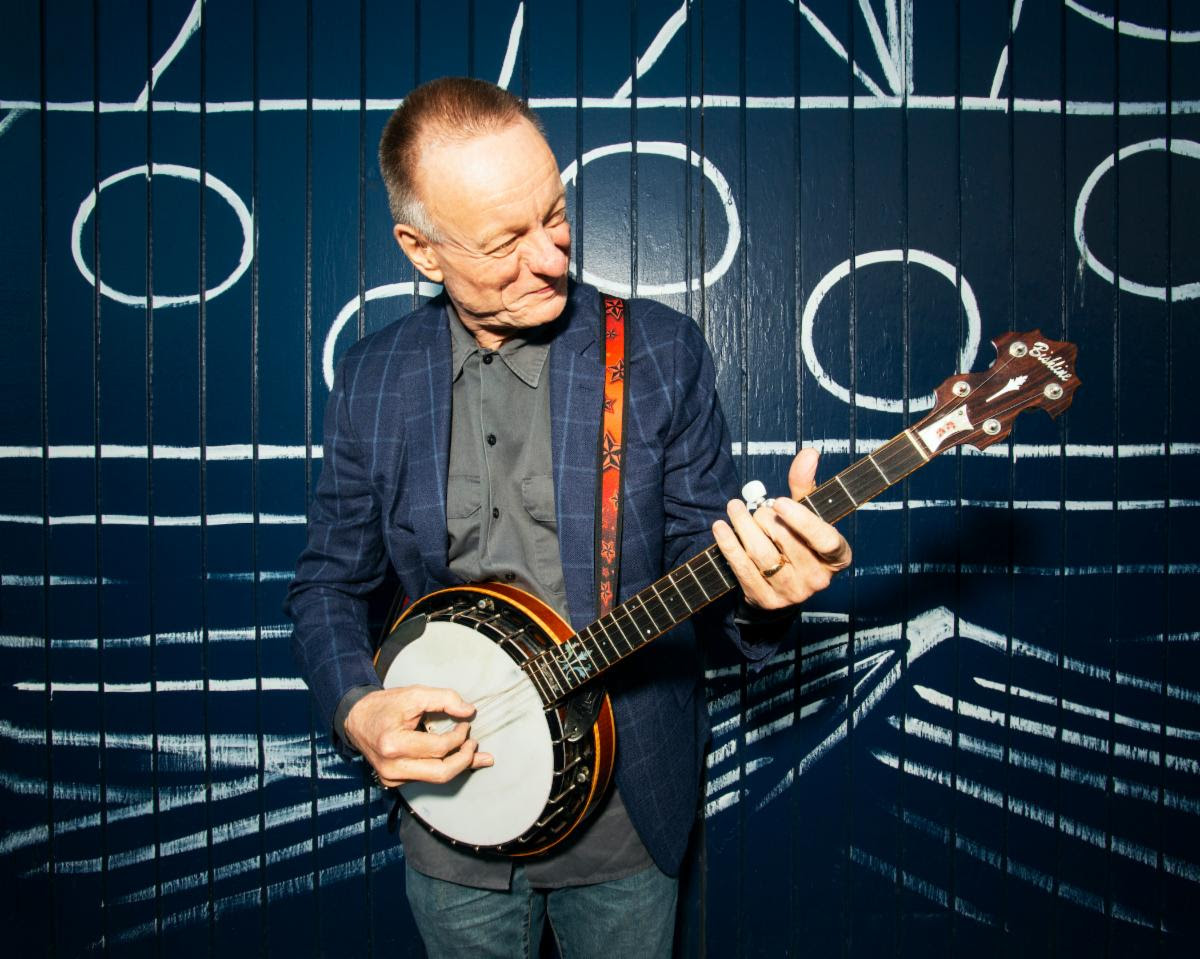

Danny Barnes’ Banjonics Chronicles (with Dave Matthews, Bill Frisell and Some ‘Crazy-Ass Music Fans’)

“I do my writing on the banjo, although it all really starts with poetry,” explains Danny Barnes, as he muses over the origins of his new album, Man on Fire. “What I’m best at is the poetry part, and the banjo is the way illustrate it. So I start with the libretto and then use the banjo to bring it to life.”

With Man on Fire, he brought his latest batch of songs to life alongside a stellar team of players: John Paul Jones on bass and mandolin, Bill Frisell on guitar and Matt Chamberlain on drums. In addition, Dave Matthews, who serves as the album’s executive producer, contributed vocals and Wurtlizer. Barnes hails his collaborators on the new record, acknowledging, “There’s a small group of these guys that I trust. I’ll say to them: ‘Hey, is this something?’ I know that what they tell me is going to be really important. The trouble with doing music is that everybody’s a critic, so you get a lot of really crappy information. That can also happen if you play in a bar. People are there to get drunk— they’re not the best judges of your music. If you start playing to that audience and trying to entertain people who are kind of loaded, it changes the music. It makes the music less interesting because it’s like shaking keys in front of a baby. You’re changing your music based on a preexisting condition, and that doesn’t necessarily lead to the best stuff.”

Like much of Barnes’ work, Man on Fire blends the timeless themes of old-time music with a modern-day, experimental aesthetic. Despite gig cancellations wrought by the coronavirus pandemic, Barnes remains active. The musician has written a new album that he plans to record with his beloved genre-twisting group, the Bad Livers. (It will be their first record since 2000). Beyond that, Barnes, who received the 2015 Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass, will continue on his singular path, selling cassettes through his own Minner Bucket label and creating zine-influenced comics.

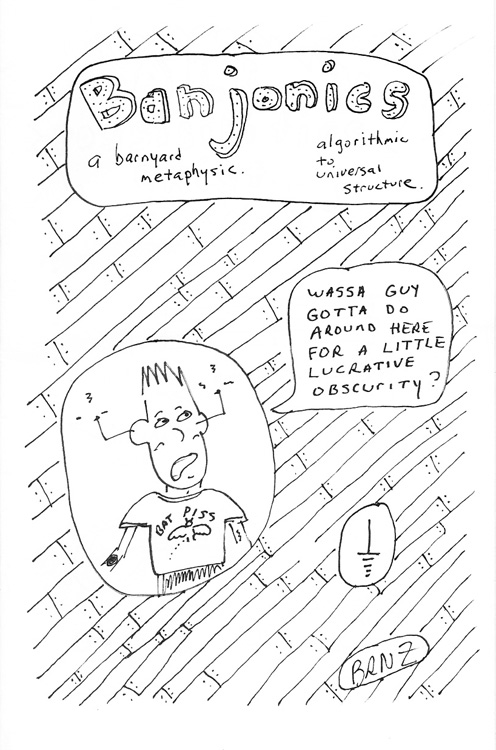

The first 20 folks who pre-ordered Man on Fire also received an original comic. You have an Etsy page where you sell a variety of your original illustrations and comics. How did that come about?

It’s totally a punk-rock zine thing. I never really drew. I was always just trying to play music. But a few years ago, I got hurt on the job. I was blasted with a loud sound. I thought I was going deaf so I started drawing. It came out of a period when I was super depressed and I didn’t know what to do. So I thought, “Well, if I can figure out how to draw, maybe that’s another way that I can get out some of my poetic and musical ideas and still have an impact on the observer.” But I’m totally unskilled, so it’s really punk-rock. When it turned out that I wasn’t going to go completely deaf, I just kept drawing anyway. I have my own little weird style, but I’ve enjoyed how you can make a universe. It’s like songs. If you write enough of them and you have this giant body of work, you create a little universe and certain characters populate it. It’s almost like a snow globe or something. So it was interesting to learn to look visually at what I had been doing with notes or syllables. I’ve made a weird little universe with antagonists and protagonists and whatnot, but I comment universally through these basic elements.

One of your comics is titled banjonics, which you note, “combines philosophy/logic and banjo playing.” Is that something you’d been thinking about for a while?

I went through a period where I liked to read books about logic—analytic philosophy and things like that. I’ve been curious about set theory and— just for fun—I read some books by people like Willard Van Orman Quine, who is a very interesting fellow. His nephew is Robert Quine, who played in Richard Hell and the Voidoids and also was on that Lou Reed record The Blue Mask. So this guy in the punk-rock pantheon actually has a philosopher uncle. Anyhow, the banjonics idea comes out of that—it’s metaphysical sort of things related to banjo playing.

I’m designing this banjo pedagogy. I’m trying to codify my own system of playing the banjo—pretty much all I’ve tried to do since 1971 is play the banjo. And so I’ve been working on a system for it, where I can take somebody who doesn’t really know how to play the banjo and get them to where they can arrange tunes, compose tunes and make things. I’ve been toying with the idea of calling it banjonics because it’s a cool word.

What initially drew you to the instrument?

I grew up in a small farming town in central Texas in the 1970s. The basic idea was you were supposed to get married, have kids and go work on the farm. Only the rich people in town went to college and everyone else was more or less going to be a laborer. But I saw Stringbean and Grandpa Jones play when I was 10 and said, “OK, I’m going to play the banjo.” My mother and dad used to just play a lot of country-western records. They did that thing where you had to look at the record player and you couldn’t talk—you had to pay attention to the record player. Music was really important to them.

In a sense, what attracted me to the banjo was the visuals because it doesn’t look like those hand motions would make this music. I also saw Buck Trent and guys like John Hartford play the banjo on TV and it looked really weird. All these notes were flying out of it and the melodies were landing somewhere in the middle. I thought it’d be the coolest thing in the world to be able to do that. If I could whip that out, it would be pretty amazing, like juggling or something.

When you watch someone play the piano, when they go down to the left, the notes are lower, and when they go to the right, the notes get higher—so you can visually tell what they’re doing by watching their fingers. But with a banjo, the strings are out of order and it doesn’t make a lot of sense. The music is buried in there. It just drew me in.

I love the banjo. I work on it all the time and I’m still learning more about it. You can play it with almost anything—you can play it with an orchestra, you can play with a punk-rock band, you can play it with a bluegrass band, you can play with a country band, you can play it by itself, you can play it with a piano, you can play with all these different kinds of things.

The whole process of learning is really good for you. And when you meet people who are into the banjo, they are usually pretty nice people because you have to be somebody special to catch that the banjo is an interesting instrument. The average person doesn’t usually come to that conclusion. So typically it’s somebody who’s a little bit elevated in a certain way, at least in terms of observation.

Over the years, your banjo explorations have taken you in many directions, often far afield from the traditional sounds that people associate with the instrument. However, a few years ago, you released your first-ever acoustic bluegrass record, Stove Up. What prompted it?

I’m always researching because there’s so much good stuff that I haven’t found yet. I constantly find great players and great songs from old-time banjo players and singers. There’s so much earth in the tradition. Take someone like Bukka White or early Bill Monroe—there was a real earth in what they were doing, and as people started playing this music in academically advanced environments, it lost some of that connection to the earth. I feel like the tradition is where a lot of the spice and the emotion of the poetry comes from.

It’s also worth studying as a songwriter—just as American literature is worth studying— because, a lot of times, if there’s something you’re trying to solve, a master will have already solved that problem.

Can you point to someone you’ve discovered in your studies that the general public might otherwise overlook?

Stove Up was an homage to this guy Don Stover. He was from West Virginia and he played in the Lilly Brothers for a lot of years. He played up in Boston at a place called the Hillbilly Ranch. They had that gig for like 20 years and, if I’m not mistaken, they played every day at this club. This guy was just an amazing banjo player. He played in Monroe’s band in the ‘50s and he’s on that record Knee Deep in Bluegrass. He was a real old-time guy, from the nexus of Ralph Stanley and Don Reno. He sang, fronted a band and played old-time and bluegrass banjo, but he also had his own sound.

Bill Keith later came up with a different style of banjo playing that allowed people to play these long-scale runs. Earl Scruggs is more like Chuck Berry—it’s more like chunks of information—whereas, when Bill Keith came along, he was able to play these longer phrases. He’s influenced Béla Fleck and a lot of other people. But Bill told me that he got the idea for that style of melodic banjo-playing by listening to Don Stover.

Meanwhile, another part of your musical life includes Minner Bucket Records where you sell cassettes. Why does that format appeal to you?

Initially, I was just comfortable with it. I’ve made records on four-track cassette machines and I have always had a lot of music on tape. I learned how to overdub by taking two cassette players, putting something on one and playing it back. Then, I’d play long and record myself with the second cassette player.

But my interest in cassettes goes beyond that. One thing that’s cool about them is that I think a little bit of surface noise is actually flattering to music. You have to filter pictures a certain way for them to look right. If you look at a movie, there’s this whole color palette thing that happens and you have to narrow things down a little bit in order to deal with them. In the same way, you can’t record everything. You have to figure out, “OK, well it’s a flute-piano duet and it’s recorded in this type of room.” In other words, there are certain sonic benefits that come with cassettes. There’s a million of these plug-ins that they sell for digital audio workstations that basically emulate a cassette player.

Another thing that’s interesting to me is that the only people that are interested in them are rabid, crazy-ass music fans. One time, I was playing this gig over in Seattle and I had some CDs and some cassettes. A guy comes up and says to me: “I can’t believe you make these stupid cassettes, who’s going to buy those things? And as he says it, a kid walks up and says, “Cassettes? I’ll take every one that you have.” So one thing I really like about cassettes is that it allows you to only deal with the music freaks. It alienates all the boneheads immediately because, if someone has got the wherewithal to be able to play a tape, then that is a person who’s interested in music.

Jumping to Man on Fire, did you write all of those songs on the banjo?

Yes, that’s always been my approach. That’s a trick I got from Hartford. He said that if you write on the banjo, it sounds a little bit different. I use the banjo because it forces you to look at things in a little bit of a different way because you’re constantly inverting things—playing these arpeggios and alluding to these things that aren’t really there. But I don’t consider myself to be writing banjo music, as it were; I’m writing songs. So I start with the poetry and then work backward off that.

My trick is: I just constantly write down little ideas I get from novels, newspapers, movies, or from overhearing other people. Sometimes I blurt things out myself. For instance, I’ve got this one song called “The Less I Know the Better I Feel.” And that came from watching the news and saying, “Man, the less I know about this stuff, the better day I’m having.”

So I write all these notes down in my little notebook, and pretty much any of them could be titles of records or songs. Then when I get ready to do some writing, I’ll take one of the phrases and just start playing the banjo to figure out how to flesh it out into something. Typically, with the songs I’m interested in, you have to have a setup, a conflict and a resolution. And then you have to land the airplane.

The songs and poems have an arc to them—an architecture—and they interact together in the overall work. There’s an arc to that as well. And if you plug those songs into my whole catalog, they fit into that arc as well. That’s the way I think about it.

What role did Dave Matthews play in the process?

I had a giant bag of songs—like 40 of them—and he helped me go through them. He’s one of my good buddies. I have about five or six of these super elevated cats that I can go to with questions like, “Hey, man, is this better than this?”

David is a super smart cat. If you go into his house, he’s got some really cool paintings on the wall. He’s got a good aesthetic eye and he’s a smart guy. Bill Frisell is also someone who has helped me evaluate what I have. Leo Kottke is another one of my good friends and so is John Paul Jones.

I don’t always ask for their guidance. Sometimes I just like to make things. But in this particular instance, what I thought I’d do is take a couple of years to write a lot of tunes and then get the best players. I wanted to make a bold statement.

What would you like people to take away from the record?

I’d like for them to take away the idea that there can be dignity for poor people. Even if you don’t have much and you’re getting kicked around, you can still have a meaningful life. What I’d like for them to take away from it is encouragement.

I’m trying to have a healthy response to everything that’s happening in the world. And what I’m trying to do with my response is make something. I just was in North Carolina, West Virginia, Virginia and Washington, D.C—meeting people, playing and finding out about the world. What I’ve tried to do with my life is figure out how I can have a healthy response to the fact that people die and things get sticky. Sometimes you don’t have all the cards in your favor but you’ve got to keep going and you’ve got to keep showing up. You’ve got to keep suiting up, and you have to be there for your family and friends. And you have to try to have a healthy response, despite what is going on in the world.

So I hope that someone takes away a little bit of encouragement from this record. Maybe somebody wants to be a writer, or wants to paint or play an instrument, or open up an art gallery or be a motorcycle racer or whatever. It’s easy if you have everything given to you but, a lot of times, you don’t; so you have to make do and you have to be really focused over a long period of time because it’s so easy to get blown off track. It’s like when someone says they’re going to take up yoga. Within about three or four weeks, they will be challenged for the first time. Maybe their hours will change at work or something else will happen, and they will need a lot of determination to go back to that yoga class. It can be hard to keep your spirits up because you kind of get beaten down.

What I’m trying to do with my music is speak to people on that level, encourage them—make them think, make them laugh—and elicit some type of response in their head and in their heart. I try to speak to them as someone who they might know a little bit, someone who cares about them and sends them on their way.

The banjo is designed to lift up the spirits of the people who hear it. I’m trying to employ it in that role. I feel like there’s a real need for it. The older I get, the more I feel music is more important than I realized. People have got to have something other than TV and their phones. Art is the foundation—the fundamental use of it is as a balm against the storms of life. That’s what I’m trying to provide with this music.