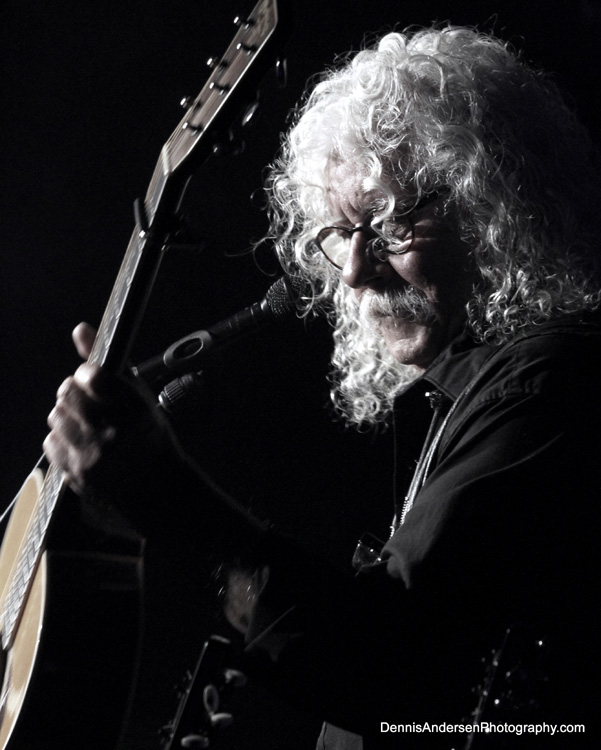

Arlo Guthrie on 50 Years of Thanksgiving at Carnegie Hall

Revolutions move in patterns, cycles, as their name suggests. We look back to the past for reference and grounding in uncertain times, and music holds a special role in that. As 2017 marks the 50th anniversary of many classic records from 1967 — Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow, Country Joe & The Fish’s Electric Music for the Mind and Body, The Velvet Underground and Nico, Songs of Leonard Cohen and The Grateful Dead, just to name a few — we’re also reminded that the come-up and come-down to that Summer of Love was rife with disquiet and pointed expression. These classics are timeless because they quite literally stand outside of time; we’re still feeling now what they were feeling then.

1967 also saw 19-year-old Arlo Guthrie, son of the beloved folk troubadour Woody Guthrie, release his debut album, Alice’s Restaurant. It would go on to be another storied classic, with an 18-minute opening track called “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” wherein Guthrie tells a Thanksgiving day story about getting caught dumping trash illegally after the dump is closed for the holiday. The illegal dumping winds up saving Guthrie from Vietnam after he visits the draft office later in the song. “I’m Sittin’ here on the bench, I mean I’m sittin’ here on the Group W bench,” he sings, “Cause you want to know if I’m moral enough join the army, burn women, kids, houses and villages after being a litterbug.”

The song became an anti-war fable, a talking number in a style championed by countless others in the folk community, along with Grisman and Garcia on Not For Kids Only. Guthrie’s debut went on to spawn a film, and even a cookbook written by the real Alice May Brock herself. The old Trinity Church that features prominently in the Thanksgiving story would later come to be a part of the Guthrie’s continued presence in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Another Thanksgiving tradition was born that year, too, when Guthrie first performed at New York’s Carnegie Hall. Each year he’d share the stage with the likes of Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins and members of the Guthrie family, bringing his community together in song. 50 years and 55 performances later, the Guthries return for the Thanksgiving tradition on Saturday as part of their Re:Generation Tour. Arlo will sing his songs alongside his kids Abe, whose accompanied him on keyboards since the ‘80s, and Sarah Lee, who brings a celebrated catalog from her own two-decades long career. Cathy, Annie, and other Guthries will also join in on the family tradition.

“The road continues to beckon and the kids, with kids of their own, are hearing the call of their own thoughts,” says Guthrie. “Onward!”

Relix caught up with Guthrie over email to learn what it feels like to keep the Thanksgiving Carnegie Hall tradition alive, how he sees folk and protest songs in the modern world, and the tastiest dish of Alice May Brock’s that he ever ate.

This Carnegie Hall tradition is maybe a different vibe than someone unfamiliar with the tradition would normally associate with you.

Carnegie Hall is very unique indeed, in that it was built to highlight the classical format of symphonic orchestras. But, for us it’s an exception. Most of the theaters we play these days were built as vaudeville venues and for a wide variety of entertainment. I love the format, and the tradition in addition to the physical spaces. I’m at home pretty much anywhere, but I do love being a link in a long chain of entertainers who’ve gone through these venues.

What does it mean to you to be playing these Thanksgiving shows for 50 years? 1967 seemed like such a transformative year for our country, I wonder how it loops around again for you with all the disquiet and revolution in the world now.

We’ve done these shows at Carnegie Hall since the late 1960’s. There are some years where we either didn’t perform around the Thanksgiving holiday, or simply had another gig somewhere else. But for the most part this particular Thanksgiving tradition was always a family event for us. For decades my wife, Jackie and I hauled the kids to NYC and did this gig, Most of all that time was with my dear old friend, Pete Seeger.

As the times changed, our audience changed also. Some years were more sparkling with a patriotic defiance than others, and some were like spending time with family and friends. Throughout it all there was, and continues to be a spirit of humanity that just won’t fade away. The hopes and dreams of generations trying to make the world a little better for everyone keeps going. I’m just happy to have been a part of it. It’s about time to hand those traditions to younger dreamers and hopers. I think they’ll handle it just fine.

You mentioned talking to an Iraq veteran in an interview with NPR over a decade ago, and you explained to him that life can be a lot like the winds and turns of a river. What are some of the unpredictable winds and turns in your own career, and how have those things come back around again?

Nobody in their right mind considers singing folk songs as a career. My buddy Tom Paxton once noted “People don’t realize it, but there’s hundreds of dollars to be make in folk music.” There was a glitch in the system during the 1960’s and I was lucky to have come up at that time. When we entered this new technological age sometime in the early 1980’s, I’d already had a catalog of recorded music. And I was able to begin our record company with a catalog rather just a single CD. About the same time I realized my audience was getting a little older and didn’t relish the idea of going to the clubs that had been my bread and butter for 20 plus years. So we began working in theaters and have been there ever since.

Protest music still takes the expected shape of pointed, naming-names screeds, but you seldom went that route in your work. Alice’s Restaurant as the most known go-to is a folk fable, an allegory, and part of a tradition — riddles and questions worked out through generous helpings of American wit. Have we lost our ability to sit with our outrage and work it out through fables, myths and storytelling?

I’ve written some pretty pointed material about individuals in the past. There’s times to call people out. But I’ve also become someone who values compassion more than I used to. I’m less judgmental when it comes to individual people, and more inclined to kick policies around with people I don’t see eye to eye with. Maybe it’s just that I’m getting older, or maybe something else is happening. In either case, I don’t think there’s only one way to deal with reality. Every voice counts whether or not they agree with each other.

You’ve quoted Pete Seeger as saying that the unifying power of music is undervalued. How do passionate creative people change that narrative?

I don’t know. The value can’t be easily seen in terms of money, so most people who profit from music have abandoned folk music as a viable business model. Most people reading this may be familiar with Hunter Thompson’s famous quote “The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There’s also a negative side.”

The common unifying value of folk music may only be in the hearts and minds of those who share in the power of the tradition. It is, after all, the original social media.

My friends in Housatonic, MA hold the old Trinity Church as such a special place, and The Guthrie Center there seems to have contributed toward keeping up the culture of that little area of The Berkshires. In an age when there are powers trying to divide us, it also seems like an interfaith place that brings people together qualifies as a revolutionary act. What does that one truth look or feel like to you these days, and how can folks spread that goodness around when they’re out in the world?

Pete Seeger told me once that “Although governments, powerful corporations, influential individuals and others can always find a way to stop large movements of people. They’ll infiltrate, lie, cheat and steal, bear false witness and do all kinds of really bad things to stop the progress of humanity moving forward. But none of these people or groups has the where-with-all to stop the millions of little ordinary people from doing things in their own back yards and in their own home towns. Think globally – Act locally.” That was our idea for the old church. We’re not trying to grow it. It’s just one more place in this world where people can meet and enjoy the company of like minded friends and neighbors.

Are there any Guthrie family Thanksgiving traditions beyond these performances?

Every family has their own traditions. Ours is no exception. But the one thing that tends to run through them all is that we tend to keep our actual traditions within the family. So to answer your question, there are more than a few family things we do, and we like keeping them to ourselves.

What’s your favorite recipe from the Alice’s Restaurant Cookbook, and why?

I don’t remember, but I loved her grape leaves and philo stuffed somethings. Anything with butter.