“A Beautiful Life Lesson”: Director Mary Wharton on ‘Tom Petty, Somewhere You Feel Free: The Making of Wildflowers’

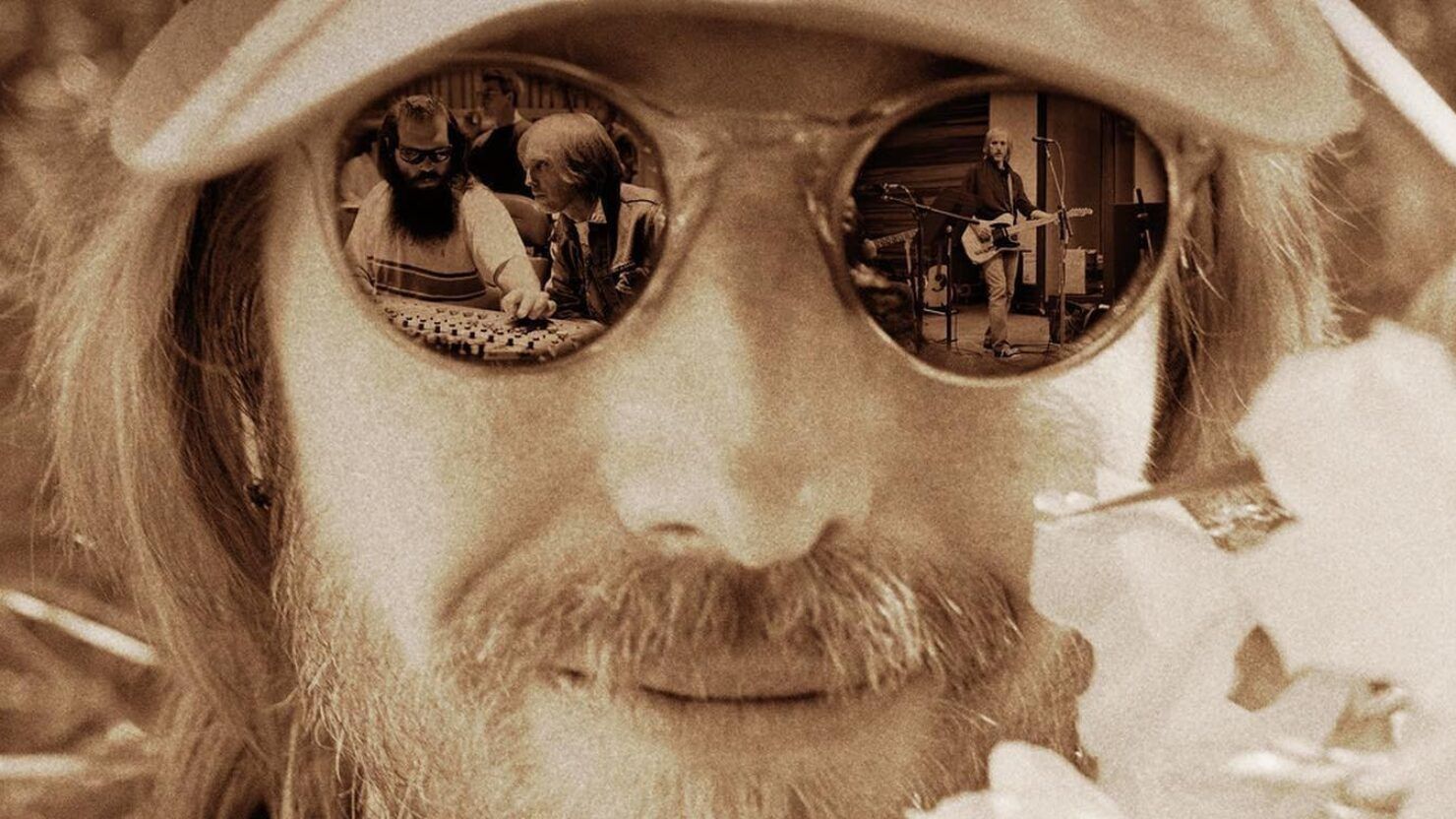

“This really came to me at the right time,” Mary Wharton says of the opportunity to work on Tom Petty, Somewhere You Feel Free: The Making of Wildflowers. The documentary draws on recently rediscovered footage to share the story of Petty’s collaboration with producer Rick Rubin on the Wildflowers album. Petty narrates much of the film himself through archival audio and Wharton also draws in Rubin, Mike Campbell, Benmont Tench, George Drakoulias and others to develop an intimate portrait of the artist.

Wharton began work on the film in the pandemic during a moment which otherwise limited her own creative output. The director, who had recently received sweeping acclaim for her film Jimmy Carter: Rock and Roll President, was foundering a bit without a project to engage her, when Tom’s daughter Adria provided an opportunity to go back to work. Wharton had previously won a Best Music Film Grammy in 2004 for her documentary Sam Cooke: Legend and her credits include Joan Baez: How Sweet the Sound and The Beatles Revolution.

Tom Petty, Somewhere You Feel Free: The Making of Wildflowers debuted at SXSW 2021 winning the festival’s Audience Award and it also took Best Documentary honors at the Boulder Film Festival. It premieres today on Tom Petty’s YouTube Channel.

Before we jump into the new film, I’d love check in on the Jimmy Carter documentary. After we spoke about the film last fall did you subsequently receive any surprising or gratifying feedback?

That aspect of President Carter’s life really took a lot of people by surprise and, and pleasantly so. It’s been wonderful to see how much joy it brought to people. I received such a fantastically happy response.

One thing that’s been really funny lately is it’s been playing on airplanes and since there weren’t that many big Hollywood movies that came out last year, the airplanes don’t have a big selection of movies. So I’m getting a ton of people who are sending me pictures of the little monitor on the back of the seat in front of them with the comment, “Look at what I’m watching.”

A friend of mine was on a Delta flight seated next to an older couple who told him that they were Republicans and he talked them into watching my film. They loved it and told him they were going to encourage all their friends to watch it. That, to me, is one of the greatest things to hear, because anyone who’s a fan of Jimmy Carter is going to appreciate the film but I’ve always tried in my work, not just preach to the choir. So to get people who might be on the other side of the partisan divide to see Jimmy Carter in a new light or appreciate him in a new way is very gratifying and surprising.

Let’s talk about Somewhere You Feel Free. What led you to take on this project and what was the timeline?

At the beginning of the summer of 2020 I heard from Adria Petty, Tom daughter, who I’ve known for many years. We actually worked together when I was at VH1 back in the 90s learning my trade as a young person making music docs. She worked with me back then and we’d stayed in touch over the years. She called me up and let me know that they had found this whole archive of film reels that they’d started transferring to digital video and thought that there was the makings of a film.

Then Adria asked me what I was up to and at that time I wasn’t doing anything due to the pandemic. At this point there was no vaccine, rapid testing wasn’t widely available and all of that was a huge hindrance to shooting or doing anything with other people. So this was an incredible opportunity for me not only because I’m a big Tom Petty fan but also because this project was mostly archival-based. So it was possible for me to work on it during the pandemic while most productions were shut down. This archive of footage presented itself and it truly felt like a box of sunshine that dropped out of the sky during what was otherwise a dark time.

We put the film together over eight months from start to finish, which was really quick. Documentaries can take a very long time. Many can take years to develop and research. However, since this one was focused on this archive, which covered a very specific period of time, that limited the scope of it.

So because there was really nowhere for me to go or anything that I could do, my editor and I just kind of hunkered down and started working. We worked long days and almost every day because it was something positive to focus on. It was really satisfying to dive into this world of the past with this footage, which was so beautiful, and this music, which was so beautiful. It was a relief to work all the time.

We made the film over those eight months and we were lucky enough to get it into SXSW, which was in March of this year. That was a sort of a deadline that we had to meet, getting it ready for that.

In terms of the assets, what sort of footage did you have to work with?

The core of the film is based around footage of Tom in the recording studio with the band, Rick Rubin and George Drakoulias. In addition, the director Martyn Atkins who filmed the recording studio material also filmed four nights of concerts on the Wildflowers tour. He made a concert film called 400 Days that was about the tour.

Then there was another batch of footage that was shot around the same time MCA released a box set of rarities [Playback (1995)] that fulfilled Tom’s obligation to MCA, his original label. They had shot some stuff with Tom in the recording studio, listening back to some of his old songs.

There’s a shot in the film where he’s standing in front of these boxes that are the master tapes for “Refugee” and that kind of stuff. It worked really well when he was talking about his history with his band and the fact that they had been together for 20 years. Then to see the boxes of their 20 years together, all piled around him was a great visual metaphor for that relationship, some of which was falling apart, as the drummer Stan Lynch left the band.

As you made your way through the footage, what most surprised you?

The one thing that was really surprising to me was a line where Tom says he felt like he was constantly trying to get better as a musician because he’d always thought of himself as not very good. Now here’s a guy who’s got more hit songs than most famous artists, and was good enough to have been in the Traveling Wilburys with Bob Dylan and Jeff Lynne and George Harrison—some of the top rock-and-roll musicians who ever lived. He’s in that company.

So the fact that he still thought of himself as not very good was pretty shocking to me. It’s interesting that he was dealing with the same kind of feelings a lot of people go through.

As someone who works in a creative field, I could certainly identify with that notion that when you’re making music, writing songs and creating records, you’re making something out of nothing, something that didn’t exist before.

Tom would go into a recording studio with an idea for a song and come out with a song, which feels like magic sometimes. There’s no formula how to be a successful musician, you can only trust your gut. So you have to be constantly questioning yourself and you’re faced with rejection all the time. That’s a difficult thing.

To hear how eloquent he was in describing that and to see him overcome all of that and lean into his creativity at a difficult time of his life, using his art to work through his personal issues, was valuable to me. I was coming at this during a difficult time for the whole country and I had just come through a difficult period myself. After putting a ton of work into the Jimmy Carter film with this whole big premiere going to happen at the Tribeca Film Festival, it was canceled in the pandemic. Then the potential financial success of the Carter film was derailed by the fact that there were no movie theaters open during that time. It was lovely that we did manage to get the film out and reach an audience. All of that is great, but it didn’t have the financial success that we were hoping for or that people were predicting for us.

So to see Tom going through rough times too and lean into his creativity was a great reminder for me that here I had an opportunity to lean into my creativity and do something that made me feel good by virtue of doing it. It was a beautiful life lesson for me and I felt like it came to me right when I needed it most.

Adria is a gifted filmmaker in her own right. Do you know if she was tempted to take this footage and create a documentary from her perspective?

She could have made a beautiful film. However she very pointedly said that she was still so grief-stricken over the loss of her father—at the point that we started on this project, he had only died three years prior—that she couldn’t bear the thought of spending her days watching footage of him all day.

I think it was difficult enough for her to get through watching the rough cut of the film. It was very emotional for her and she knew that it would have been too rough to deal with that heartbreak on a daily basis.

What was your initial vision for this film and how did it evolve over time?

I approached it as a little time capsule of a self-contained story. There had been a four-hour documentary made about Tom Petty by Peter Bogdanovich back in 2007 [Runnin’ Down a Dream], so that sort of relieved me of any notions or even responsibility to provide a wider story because that had been told already. So I decided that the framework would be the making of a specific album and then I’d use that structure as a lens to look at Tom.

I also was hopeful that we would paint a portrait of this artist and give people a view of him that they had never seen before. His creative process is not something that he typically showed to the public. Even Tom’s daughter Adria said to me that she had never seen Tom and the Heartbreakers woodshedding a song like they do in the footage. It kind of surprised me that they kept their creative process such a private little that even Tom’s own daughter had never seen it before.

So that was what was really interesting to me about it, basically getting to sit at the feet of the master. Here was this musician who was at the top of his game in this time period, with all these resources available to him. He got to live in this world of making Wildflowers for two years, which is a long time to spend making a record. So ultimately that formed my creative direction of what we were trying to do. Then the way it all came together was very organic.

We never really changed the order that we present things from the way we set it out in our first edit. The sequencing of the film that we laid out stayed the same to the very end, which is very unusual. That typically doesn’t happen in documentaries—you’re often trying to find the best way to lay out your story in the edit room, because you can’t really script it in advance. You have to figure out what you have and then you often play around with it and switch up the order of things, because you’ll realize: “This would work better if we have scene A here and scene B there.”

So these things oftentimes get switched around but in this case, they really didn’t. I think it’s because what we initially put together just felt right. There was no rhyme or reason to why things came together as they did—we weren’t trying to follow the order of the songs on the record and we weren’t trying to follow a timeline of when things happened. We don’t follow any of those things at all. There’s no semblance of chronology really at all in the film. Still, somehow it all just clicked together.

There’s a moment early on in the film when Rick Rubin mentions that there is a lot more going on in the song “Wildflowers” than one might initially appreciate. Then you play a portion of the song so that the audience can listen more closely. That almost seemed to be a metaphor for the film as whole.

I think one of the joys of watching a music documentary like this is hopefully it does make you hear things differently and pay attention to things in a different way than you would have. It is such a joyous surprise when suddenly you have your head turned around about things that you think you’re so familiar with. You’re like, “Oh, wow. I never noticed that before.” I mean, isn’t that fun?

Did you have a favorite song on Wildflowers going into the project and did that change as you worked on it?

I think that before my favorite song was “Honey Bee” because it’s such a great rocker. It’s a fun song that’s got bit of a cool, raunchy vibe. But I really grew to love “Wildflowers,” the title track. I listened to it over and over again. That and “Wake Up Time” are my two favorite. Those are the first and the last song on the record but they both have a similar kind of message, which is about believing in yourself.

With “Wildflowers” he’s giving himself permission to feel free and, and with “Wake Up Time” he’s reminding himself that we’ve all been knocked around a little bit, but if you believe in yourself, you’ll probably be okay. Those are two intertwined messages that bookend the record and in some ways bookend the film. They’re both very powerful and important things to remind ourselves, whenever we can,

After seeing the film, I kept coming back to “Wake Up Time.”

It’s a beautiful song. And one of the things that was really cool about this project was we had access to a lot of the multi-track recordings. So the editor Mari Keiko Gonzalez did a beautiful job with “Wake Up Time” where it starts with just Tom’s piano and vocal tracks, then as it builds up she cuts to a live performance.

I’ve seen this film a hundred times, but whenever we get to the place where the “Wake Up Time” live performance kicks in, it always makes me cry because it’s so beautiful.